When Jorge M. Pérez was an undergrad at C.W. Post on Long Island in the early 1970s, he discovered he was pretty good at poker—good enough that his pockets were often stuffed with plenty of walking-around money, the kind typically used for date nights or the keg fund. But Pérez, who was born to Cuban parents in Buenos Aires and spent his formative years in Colombia, had different priorities. “A lot of my college mates bought posters of rock bands or of ladies,” he recalls, “and every time I had a hundred bucks I’d go to New York City to look at lithographs.” Poker earnings allowed the young Pérez to decorate with Man Ray and Joan Miró instead of Led Zeppelin and Raquel Welch.

Animating the family room are an Ettore Sottsass ceramic sculpture, a Katherine Bernhardt painting of fruit, and an Alex Katz portrait over the TV and a floating shelf by Arthur Casas; a sectional sofa custom made by Louis Interiors wraps around nestling tables by Christian Woo, and an Apparatus light fixture is mounted above an Angelo Mangiarotti table and William Gray chairs. Photo: Kris Tamburello

It was the beginning of a lifelong commitment to art. Pérez translated his poker skills into serious business acumen, founding the powerhouse real estate development company Related Group in Miami in 1979 (he remains chairman and CEO), and he funneled significant portions of his wealth into becoming one of America’s foremost collectors and museum patrons. Following Pérez’s donation of a large chunk of his Latin American–centric art collection, along with a $20 million gift, to the Miami Art Museum, the institution was renamed in his honor in 2013, when it moved into a new tropics-friendly, pavilion-like waterfront building designed by Herzog & de Meuron. The Pérez Art Museum Miami—or PAMM, as it’s commonly known—has been central to the city’s emergence as a global art capital and a crucial Latin American cultural nexus. Nearby, Peréz recently opened El Espacio 23, a 28,000-square-foot contemporary art space.

Offering expansive views of Biscayne Bay, the pool terrace is outfitted with RH chaise longues and a custom-made dining table with chairs by Roda. The small lights mounted to the overhang are by Allied Maker, and the marble sculpture is by Zilia Sánchez. Photo: Kris Tamburello

For more than two decades, Pérez and his wife, Darlene, a clinical researcher in the field of gastroenterology, lived surrounded by their paintings and sculptures in a baronial, Venetian-style palazzo in the Hughes Cove neighborhood of Coconut Grove. “The style was very Ralph Lauren,” Pérez says. But earlier this year, he and Darlene chose to shake things up. As Pérez’s collecting has shifted from Latin American art to Abstract Expressionism and other postwar American works, the couple decided they wanted to live in something more modern and minimal, while having ample space for hosting their children and grandchildren. They found what they were looking for in nearby Park Grove, a Related Group development featuring a trio of residential towers created by a design dream team: Shohei Shigematsu from the Rem Koolhaas–helmed firm of OMA was the lead architect, landscape designer Enzo Enea oversaw the gardens, and Will Meyer and Gray Davis of Meyer Davis handled the interiors.

A sprawling Paul Jenkins canvas occupies a wall in the sitting room, where Forest & Giaconia sofas clad in a Holly Hunt velvet face a modular P. Tendercool table topped by Gaetano Pesce vases and a sculptural platter by Viola Frey; an Elio Monesi floor lamp stands between Vladimir Kagan armchairs, and a Kara Walker wagon sculpture rests on one of the Elan Atelier side tables. Photo: Kris Tamburello

“The trick was letting art take an active role in defining the spaces, balancing art and interiors in a very luxurious, comfortable, and approachable way”

Will Meyer

“It’s a wild, sculptural building,” Meyer says of the tower where the Pérezes reside in one of the penthouses. “It moves you and elevates you.” Art was baked in from the get-go. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Surrounded Islands, the 1983 installation that rimmed islands in Biscayne Bay in pink fabric, inspired the building’s undulating façade. The double-height lobby is filled with art from the Pérez collection. And the Pérez home, occupying two floors with balconies overlooking an expanse of turquoise water arrayed with boats at Dinner Key Marina and the Coconut Grove Sailing Club, is an object lesson in how to live passionately with art.

A multipart Polly Apfelbaum work beckons at the end of a hallway with abstract paintings by Elaine de Kooning (left) and Günther Förg. Photo: Kris Tamburello

A work by Louise Nevelson overlooks the dining area’s Profiles table and Minotti chairs. Photo: Kris Tamburello

For the Pérezes, there is no other way. “They love to live with their art,” says Patricia Hanna, Related’s art director. “They don’t buy to put things in storage.”

Meyer concurs. He says the trick with the penthouse was not simply hanging art on the walls but letting art take an active role in defining the spaces, “balancing art and interiors in a very luxurious, comfortable, and approachable way,” as he puts it.

A crumpled-metal sculpture by John Chamberlain presides over Darlene and Jorge M. Pérez’s living room at the top of an OMA-designed building in Coconut Grove. Will Meyer and Gray Davis, the duo who oversaw the interior, grouped sofas and swivel chairs by Minotti with vintage Marco Zanuso lounge chairs around glass-top Amorph tables, arranging everything on a copper-wire rug by Hechizoo. One of Sol LeWitt’s open-cube sculptures stands near the window, which is framed by Donghia fabric curtains. Photo: Kris Tamburello

He and Davis designed the foyer around a site-specific piece that Mexican artist Carlos Amorales executed in pencil directly on a wall, which in turn harmonizes with a charcoal-and-red-chalk Fernando Botero hanging nearby. In the living room, an outsize John Chamberlain sculpture of crumpled metal and a dazzling, 17-by-18-foot rug woven from copper wire by the Bogotá-based atelier Hechizoo helped dictate the choice and arrangement of furnishings, down to the slate-blue Marco Zanuso lounge chairs. (Pérez has recently caught the bug for collectible design, acquiring works by Ettore Sottsass, Marc Newson, and the Haas Brothers, to name a few.)

In the office, figures of soccer players by Johannes Mashego Segogela line the bespoke shelves, while a John Wigmore light sculpture is installed over a custom-made KGBL table and Marc Newson chairs; on the far wall, a Helen Frankenthaler canvas hangs above a cabinet by Orfeo Quagliata. Photo: Kris Tamburello

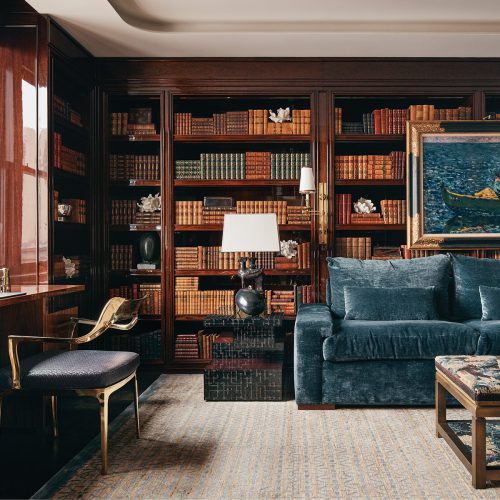

Meyer and Davis tailored the custom shelving in Pérez’s office to display Yinka Shonibare’s installation The American Library Collection (Poets, Philosophers, and Physicians), comprising 675 volumes covered in his signature Dutch wax print textiles. And the dining area—all sleek and calm, with stark white walls—was formulated to let an expansive Kenneth Noland abstraction and a stunning, ink-black Louise Nevelson sculpture take center stage. “I just wanted the art to pop,” Pérez says. It does.

“The Pérezes love to live with their art. They never buy to put things in storage”

Patricia Hanna, art director, the Related Group

A Joan Mitchell triptych commands one wall of the primary bedroom, which is furnished with a bed custom made by KGBL and dressed in Yves Delorme bedding; Losh Design lamps top the Lawson-Fenning nightstands, and the sofa is by Philippe Malouin for SCP. Photo: Kris Tamburello

Darlene’s favorite pairing is the placement of huge landscape-inspired abstractions by Joan Mitchell and Jennifer Bartlett facing each other on opposite walls in the couple’s bedroom—a dialogue between two great American women painters. Her husband loves them, too. “I don’t want to wake up without them,” he says.

Paintings by Herbert Brandl (left) and Rosa Loy add visual punch to a guest bedroom with a CB2 bed, Arteriors sconces and side tables, and a Stua chair covered in a Maharam fabric designed by artist Sarah Morris. Photo: Kris Tamburello

Perhaps the defining moment of the apartment can be found in a corner of the dining area. Here, a vivid Frank Stella canvas is reflected in a Campana Brothers’ fractured mirror, which distorts the Stella’s cool geometry into an explosive visual jigsaw puzzle. “That little corner is so special,” Pérez says, summing up what daily living is all about in this art-forward penthouse. “Art is life to me—it’s a passion. I can sit there and just look at that corner and go, ‘Wow!’ ”

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2021 Winter Issue under the headline “Fresh Perspective.” Subscribe to the magazine.