A Love Letter to The Met: Curators Share the Works They Miss the Most

The museum’s director, Max Hollein, and a group of leading curators reflect on their favorite pieces during this time of isolation

This month marks the 150th anniversary of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It was meant to be a joyous occasion, kicking off a year of celebrations with special exhibitions and events that were months in the making. But when COVID-19 hit, the storied institution—along with others around the world—was forced to shutter to the public, with all programming put on pause through June at the earliest.

The Met was founded in 1870 as a simple yet powerful idea by a group of intrepid New Yorkers to bring art to the American people. The founders believed that the developing city should have a museum equal to the great collections of Europe—but there was no building and no art. Today, it is the largest art museum in the country, with a collection of more than two million works that span 5,000 years of art history, across 17 curatorial departments. Last year, The Met was reportedly the fourth most visited museum in the world, drawing nearly 6.5 million visitors to its three locations; the main building on Fifth Avenue, the Met Breuer, and the Met Cloisters.

As culture as we know it has come to a standstill, The Met’s custodians are now mostly bunkered down in their homes, passing the time researching, reading, and reflecting. Galerie wanted to find out the works that they have been thinking about. Read on to discover the fascinating backstories behind these treasured objects, from the department of Medieval Art and European Sculpture to Decorative Arts, and why they have had such a lasting impact.

Max Hollein | Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Fortune-Teller (circa 1630) by George de La Tour

“As I continue to make regular trips to The Met, where a small group of our essential staff remains hard at work, I’m struck by the eery emptiness of the place. One of my great joys is seeing people experiencing the art and galleries, communing both with each other and the great masterworks on view. But now, day after day, as I wander the empty galleries, I’m noticing that my perception of certain works is evolving as I try to process this time of isolation, grief, fear, and uncertainty. For example, one of my favorite works at The Met is George de La Tour’s painting The Fortune-Teller from around 1630, with its theatrical depiction of a story of youthful ambition and deception. Typically, it’s the composition, color, and the lighting that I find so compelling—the darting glances, the covert gestures. But now, when I see this group of figures in a public space so tightly positioned within the frame, my first thought is, Stand back! Social distance! I realize that we’ll all carry a new lens through which we’ll view our new world. I look forward to seeing this work again among visitors when we can safely welcome our staff and audiences back to this beloved collection.”

Stephanie L. Herdrich | Assistant Curator of American Painting and Sculpture

The Wyndham Sisters: Lady Elcho, Mrs. Adeane, and Mrs. Tennant (1899) by John Singer Sargent

“Sargent’s portrait of The Wyndham Sisters, painted in 1899, transports me to another time and place. The monumental depiction of the three impossibly stylish sisters, shown in the drawing room of their London home, epitomizes fin de siècle cosmopolitan opulence with its lavish furnishings and extravagant vases of magnolias. Sargent conveys a mannered elegance in his depiction of these impossibly graceful women with their attenuated figures, long necks, and slender arms.

“Perhaps what I love about it the most about The Wyndham Sisters is that it’s a tour de force of Sargent’s mastery of white pigment. It’s a massive painting (about ten feet by seven feet), and it’s easy to get lost in his technical virtuosity. In his rendering of the gowns and the sofa upholstery, Sargent merges calligraphic strokes and daubs of paint to represent the luscious textiles. When viewed from up close, there’s an amazing abstract quality to his white-on-white painting technique. You sense the artist’s exuberance and energy channeled into every brushstroke. As you stand back you see the patterns on the brocade of the sofa and the texture and finishes of their dresses emerge. Sargent sought to make his technique look effortless—and in this bravura painting, he has succeeded.”

Recommended: A First Look at The Met’s New British Galleries, Designed by Roman and Williams

Wolf Burchard | Associate Curator, Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

A gilded-wood bench (before 1807) by Thomas Hope

“The object that comes straight to mind is our Hope bench. It was designed by the glamorous Regency art collector Thomas Hope and recently acquired by The Met specifically with the view of furnishing our new British Galleries, the 19th-century section of which still presented significant gaps. It was made at a highly important moment, the transition from the Age of Enlightenment into the Industrial Revolution. Visually extremely striking, it is a masterpiece of furniture design that would be at home in almost any environment. Wouldn’t it look splendid in a white modernist interior?

“Rather like most pieces of historic seat furniture, our Hope bench did not retain its original covers. I’m a great textile enthusiast and hugely enjoyed the collaboration with my wonderful colleague, conservator Nancy Britton, who recovered the bench. Although one may immediately associate such a piece with elegant silks, Nancy discovered red wool fibers on the bench’s original bolsters—as did our colleagues at the Cleveland Museum of Art on a sofa equally designed by Hope. So we all took a deep breath and decided to reupholster ours in a red wool to re-create what we believe may have been its original appearance. The end result is a staggering contrast between the burnished gilt-wood frame and the highly saturated color of the deep fabric—a magnificent example of the flashy and rather sonorous last gasp of the Georgians.”

Joanne Pilsbury | Andrall E. Pearson Curator, Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas

A face beaker with pumas and snakes (12th–15th centuries)

“Among the many objects of wonder and delight in the ancient American collection at The Met is one object that has been much on my mind in recent weeks: a gold beaker probably made around the time of the rise of the Inca Empire in the 15th century. Filled with maize beer, such vessels were part of convivial gatherings, essential components of community building. The imagery—two faces, puma heads, and serpents—is fascinating, but it is the work’s back story that has particular resonance for us today. The object was found on a farm near Lima, Peru, and it was sent by ‘the orphans of Lima’ to the New York Herald to be auctioned for the benefit of those left fatherless and motherless by the great Galveston storm of 1900—the single most deadly natural disaster in U.S. history. Shown at The Met from December 1900 to February 1901, it was purchased by an anonymous donor at the time and eventually given to the museum. It is a work that reminds us of the profound bonds of social gatherings but also of empathy and connections that transcend borders and time.”

Recommended: How Jewelry Has Transformed the Body for Millennia

Jeff L. Rosenheim | Joyce Frank Menschel Curator in Charge, Department of Photographs

From the Viaduct, New York (1916) by Paul Strand

“What to make of this strange and unexpected photograph by Paul Strand? Of all the works included in our just opened/just closed exhibition, “Photography’s Last Century: The Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas H. Lee Collection,” it seems to haunt me the most. The photograph dates from 1916 and is the earliest in the show, but it looks more like a Robert Rauschenberg Combine from the 1950s or 1960s than an American work of art in any medium from the 1910s. Nearly twice the size of most photographic prints by his contemporaries and composed of velvety black tones and bright white highlights, it confirmed Strand’s break with the tired, soft-focus Pictorialism of the era and established the artist as a cutting-edge modernist.

“Strand’s mentor and gallerist, Alfred Stieglitz, reproduced the photograph in the final issue of his deluxe quarterly, Camera Work, in June 1917. There, he described his protégé’s work as ‘brutal’ three times in one short paragraph. Perhaps that is why From the Viaduct calls out to me so emphatically through the painful disassociation that defines my time away from The Met during the coronavirus pandemic: The photograph arrests the eye, the intellect, and time itself.”

Melanie Holcomb | Curator, Department of Medieval Art and the Cloisters

A ring brooch from the 13th century

“I can’t wait to get back to The Met to have a close look at this little gem of an object on view in the Medieval Galleries: a gold and garnet dress pin from the 12th century. It is no bigger than a nickel, but it has grown in my mind in this moment of social isolation because of the touching inscription that follows its contours.

“In old French it reads, ‘I am here in place of a friend,’ signaling that it was surely a gift from a lover to his lady. It reminds me of how human beings have a long history of using beautiful things to cope with the absence of someone dear. I like to imagine how this deeply personal piece of jewelry, worn close to the heart, must have both thrilled and comforted the woman who wore it long ago, drawing her nearer to a distant beau.”

Kelly Baum | Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky Curator of Contemporary Art, Department of Modern and Contemporary Art

Homage to Malcolm (1965) by Jack Whitten

“This spring, The Met was supposed to open a new collection display in its modern and contemporary galleries. On the checklist was Jack Whitten’s Homage to Malcolm (1965), a powerful, expressionistic sculpture made of carved wood and pieces of scavenged metal. This is the work with which I’m most excited to reunite when we reopen. I first came to know Homage to Malcolm through an exhibition on Whitten’s sculpture that I cocurated in 2017–18. We acquired it for the collection one year later. Homage to Malcolm is a memorial that celebrates the extraordinary life of Malcolm X.

“Created at a moment when Whitten was struggling to establish himself in the New York art world, it also speaks to the persistence of creativity, the relentless drive to invent even under the most trying of circumstances. Inspired in part by the artist’s encounter with Kongo power figures (Nkisi N’Kondi), wooden sculptures designed to house mystical forces, Homage to Malcolm presents as an abstract representation of a human arm that stretches outward, its every muscle coiled with potential energy and tensed with anticipation. In so many ways, Homage to Malcolm simultaneously allegorizes and concretizes will, tenacity, and perseverance.”

Recommended: 7 Remarkable Events from The Met’s 150-Year History

Shanay Jhaveri | Assistant Curator, Department of Modern and Contemporary

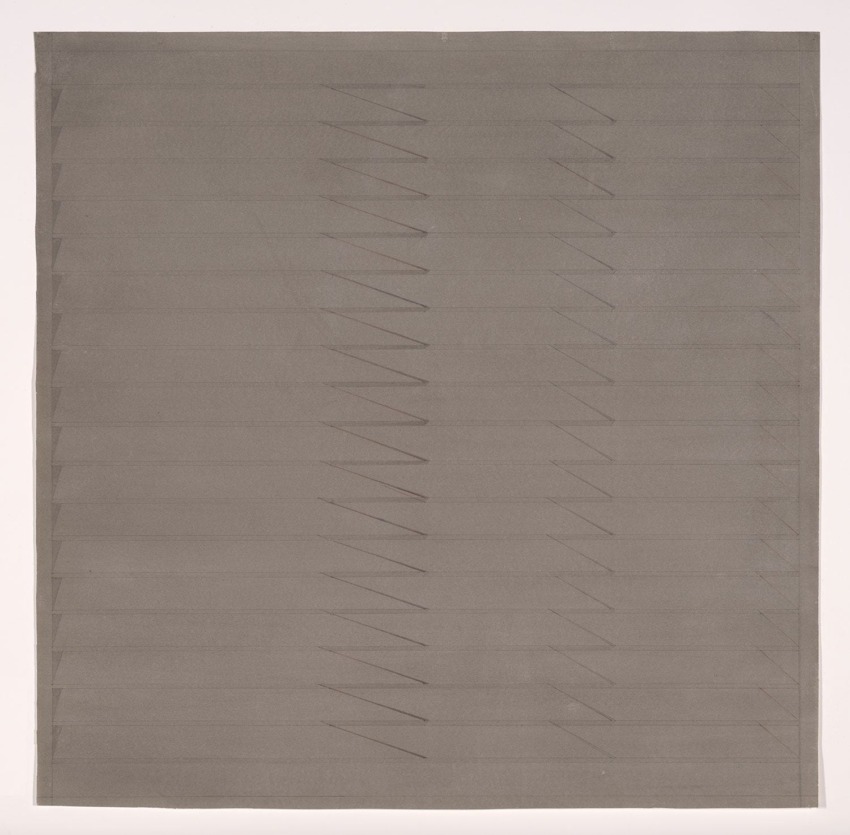

Untitled (circa 1970) by Nasreen Mohamedi

“In 1968 the Indian artist Nasreen Mohamedi noted in her diary, ‘One creates dimensions out of solitude.’ An apt expression when most of the world finds itself in isolation, reminding me of her Untitled (circa 1970), a quiet and elusive work in which a realm of patterned, ruled lines appears to be subtly and effortlessly emerging from a gray wash. A little-known fact about Untitled is that in late 2016 following Mohamedi’s retrospective at The Met Breuer, I visited with Zarina Hashmi at her New York studio. Nasreen and Zarina became friends in the early 1970s, when they lived in New Delhi. Zarina recalled that they ‘rarely discussed each other’s work but had great respect for each other as we pushed our own aesthetic boundaries. Nasreen seldom talked about her work, as she knew exactly what she wanted to do.’ Astounded to learn that The Met did not have a work by Mohamedi in its collection, Zarina immediately decided to gift Untitled to the museum, which Mohamedi had given her as a token of her appreciation when she stayed with her in 1980, when visiting New York. Untitled’s presence at The Met is a testament to not only a pioneering female artist’s aesthetic virtuosity but also to an enduring friendship.”