Louise Nevelson’s Rare Jewelry Transforms Found Objects into Miniature Wearable Sculpture

The trailblazing artist regarded her adornment as an extension of her fierce, idiosyncratic persona

One man’s trash was Louise Nevelson’s treasure. Inspired by the Surrealists’ use of found objects and the geometric principles of the Cubists, the pioneering sculptor is celebrated for her distinctive, monumental works. Less known, however, is her experimentation with jewelry, which like her larger sculptures, was primarily comprised of discarded wood covered in black paint to mask the object’s utilitarian purpose.

“Nevelson’s jewels were such a part of her persona that people don’t remember or realize that she actually made them,” says Martine Haspeslagh, who, together with her husband, Didier, runs the London-based Didier Ltd. Since opening in 2006, Didier has been a secondary art market leader for jewels made by 19th- and 20th-century artists, designers, and architects. Unlike Alexander Calder, whose handmade pieces of jewelry were almost as coveted as his iconic mobiles and outdoor sculptures, Nevelson created only around 200 jewels, adding to their contemporary allure.

Drawing largely from Didier’s 2019 catalogue, Paint It Black: The Jewels of Louise Nevelson, which could be considered the most comprehensive look at Nevelson’s jewelry to date, we trace how her various artistic practices are intertwined.

Louise Nevelson on the Power of Black

With the creation of her first black wall environment, Sky Cathedral (1958), now in the collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the 1950s marked a turning point in Nevelson’s career. The artist found a rare power in the color black, and critics, too, responded to her increasingly monochromatic aesthetic.

Recommended: A Love Letter to MoMA: Glenn Lowry and Curators Share the Works They Miss the Most

In Dawns & Dusks (1976), a book of taped conversations with Diana MacKown, her assistant and longtime friend, Nevelson said of the color: “When I fell in love with black, it contained all color. It wasn’t a negation of color. It was an acceptance. Because black encompasses all colors. Black is the most aristocratic color of all. . . . You can be quiet, and it contains the whole thing. There is no color that will give you the feeling of totality.”

As Nevelson’s fame skyrocketed, jewelry became yet another vehicle to merge her art with her public persona. Initially adhering to her familiar monochromatic palette, Nevelson treated clothespins and piano keys as she would balusters and chair legs in her sculpture. Black-painted wood formed the core of her jewelry, which proved to be the ideal medium for incorporating discarded bits and baubles that would otherwise get lost in monumental displays.

Recommended: 10 of the World’s Most Famous Emerald Jewels

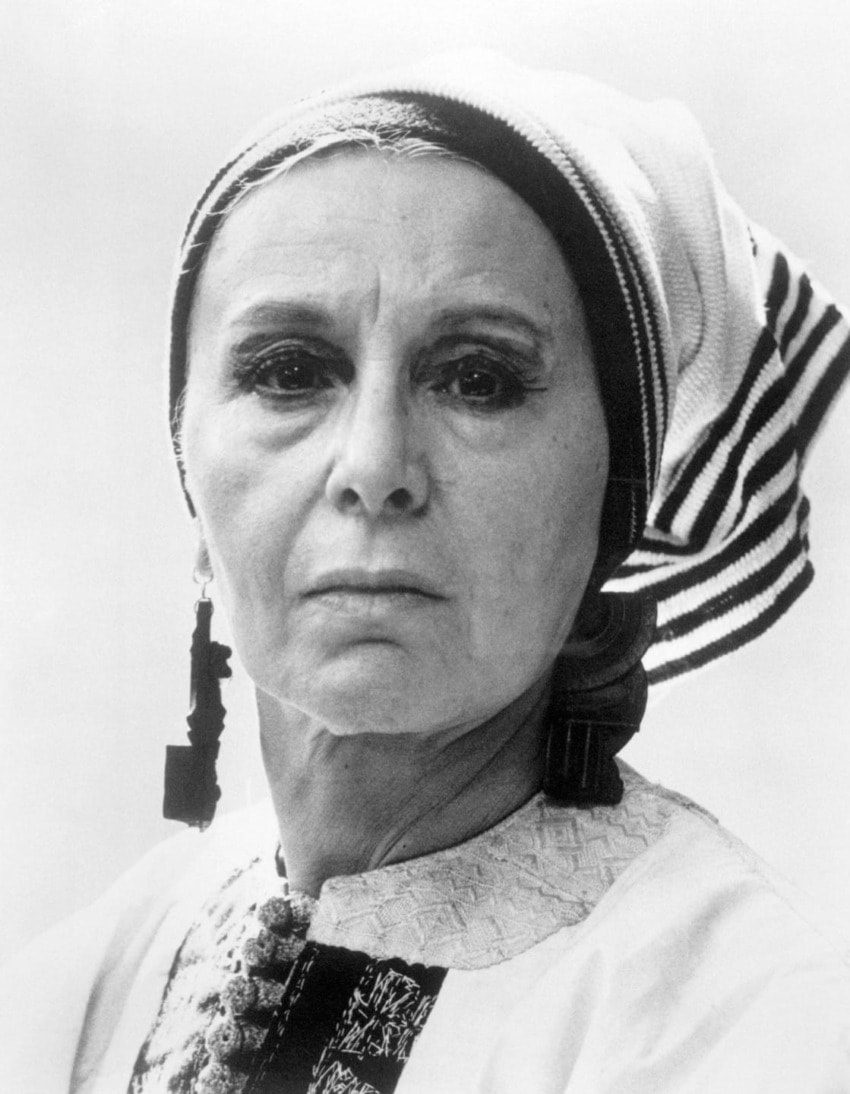

While Nevelson frequently wore costume and ethnic jewelry throughout her life, the artist’s handmade dark, asymmetric, jagged accessories were now as synonymous with her eccentric image as her enormous false eyelashes. Nevelson’s theatrical ensembles and daring personal style eventually landed her a spot on the 1977 International Best Dressed List. In Dawns & Dusks, she told MacKown, “My whole life is one big collage. Every time I put on clothes, I am creating a picture, a living picture, for myself.”

During her lifetime, Nevelson’s jewelry was included in a number of exhibitions. Of note was MoMA’s 1967 traveling exhibition, “Jewelry by Contemporary Painters and Sculptors,” where her striking black-painted wood and gold earrings—then, in the collection of artistic patron and philanthropist Vera List—were featured on the catalogue’s cover. List had purchased the jewel from Pace Gallery for $1,200, along with a brooch for $1,200 and a bracelet for $2,000. Considering these pieces were often comprised of just wood scraps, this was no small sum.

Nevelson’s Experimentation with Metal

Later in the 1960s and into the ’70s, Nevelson would work with a metal jeweler to add 14K yellow or white gold to her repertoire. “The minute you have gold it takes you over,” Nevelson noted in Dawns & Dusks. “It’s splendor. And an abundance. And that abundance is really materialistic.” Part of the joy and intrigue of using found objects in her art was the ability to transform them into something of value—even wooden debris could be gold.

In the 1980s, at a time when she was using mirrors in her sculpture, she began to incorporate brass and silver into her jewelry creations. Whereas her earlier structures explored depth and shadow, mirrored surfaces allowed for reflection in both senses of the word.

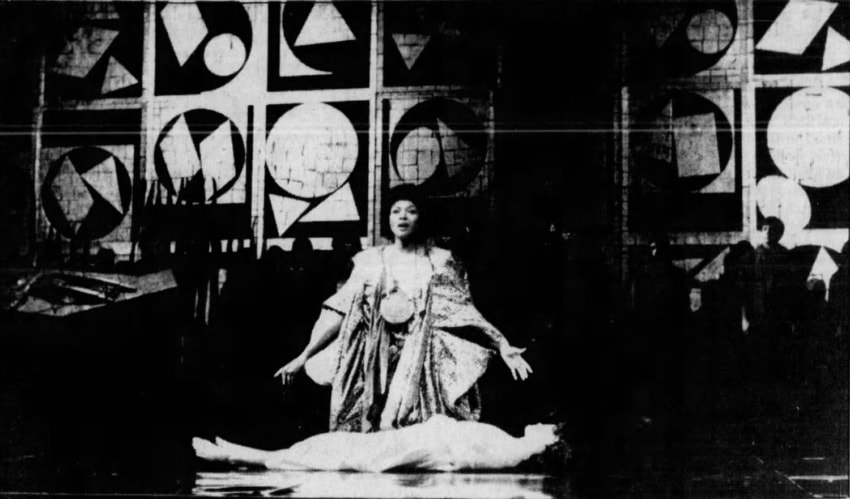

Nevelson’s growing interest in metal also influenced her theatrical work. Along with architect Bill Katz and art writer Willy Eisenhart, the artist designed the sets and costumes for the Opera Theatre of St Louis’s 1984 production of Orfeo ed Euridice. True to her high-low approach to jewelry, Nevelson adorned the characters with black-cord necklaces featuring pendants made of crushed cans. On one side, the cans were painted black, and on the other they were gold, creating a dazzling effect under the bright stage lights.

At the show’s opening night after-party, Nevelson gifted the staff necklaces of a similar design—except this time, according to Eisenhart, she arranged for a truck to run over the beer cans in order to secure more of this key component. “Does Tiffany’s have anything as beautiful as this?” she once asked Katz.

Where Are Nevelson’s Jewels Now?

When Nevelson died in 1988, a trove of more than 80 pendants and brooches (all dating from 1980 to ’85) were found at her home, leading Haspeslagh to suspect a new jewelry project or exhibition may have been in the works. Given Nevelson’s age, the intimate medium would be far easier to execute than sculpture, too.

Recommended: Now Is a Great Time to Invest in Furniture Designed by Architects

The Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, Maine—Nevelson’s American hometown—currently has one of the largest collections of Nevelson’s work, including more than 20 jewels. Other pieces were purchased by Pace Gallery, as well as Richard Gray in Chicago and Baldwin Gallery in Aspen. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection also has four of her handmade necklaces, which she dons in her famous Richard Avedon portrait.

Nevelson’s Feminist Legacy in Art and Jewelry

Nevelson proudly spoke of herself as just an artist, rather than a female one. Though she believed the adjective undermined her success, she remains a key feminist figure for both her fine art and jewelry. When she got her start, women were not considered suitable sculptors, yet she refused to do anything but prove herself a force in the field.

In their staggering, unconventional physicality, Nevelson’s jewels reflect the artist’s unapologetic embrace of an independent lifestyle. Haspeslagh, moreover, points out that very few women artists experimented with jewelry in comparison to their male counterparts, and when they did, they rarely incorporated gems. While Sonia Delaunay and Niki de Saint Phalle used paint or enamel to inject color into their jeweled creations, colored stones and diamonds were either nonexistent or used sparingly in collaboration with a jeweler. Haspeslagh believes that historically women were creating jewels to satisfy their own quests for beauty, free of the male gaze. “For female artists,” she states, “the jewels they made are works of art, not because they are precious or expensive, but because they are pieces of personal adornment.”