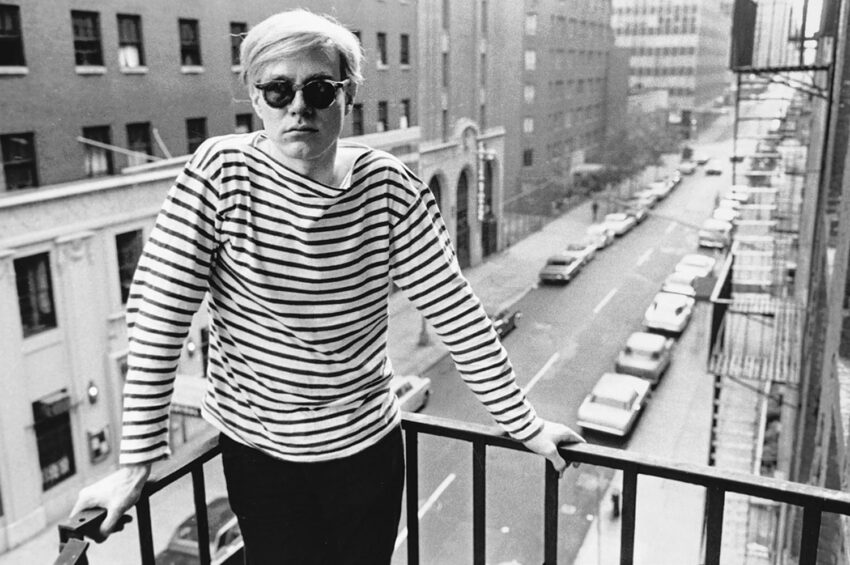

The Story Behind the Whitney’s Blockbuster Andy Warhol Retrospective

The first U.S. retrospective since 1989 casts the legendary Pop artist in a magical new light

When the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York opens “Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again,” on November 12, expect the Avengers: Infinity War of the art world: Lines will be long, reviews will be ubiquitous, and social media will be clogged with the hashtag #WarholxWhitney.

As blockbusters go, the show will give the people what they want: Pop icons Marilyn and Liz, “Disaster” paintings, and films with the Factory’s “superstars.” But the woman behind it, Donna De Salvo, the museum’s deputy director for international initiatives and senior curator, is also determined to break new ground.

To that end, the retrospective, the first on the artist organized by a U.S. museum since 1989, will include some of his less frequently exhibited works. De Salvo, a noted Warhol authority, begins with the premise that he might never have become an artist if his choice of career—fashion illustrator—had not been disrupted. Photography, he once told her, had made his skill obsolete. “The jobs,” she says, “dried up for him.”

So began his decades-long determination to stay ahead of technology. His reliance on silk-screening to replicate photographic images may be his most famous and lasting innovation, but he was a restless experimenter. A Playboy magazine commission, for example, led him to make images of Playmates with fluorescent paint, rendering the nudes visible, ironically, only under black light.

The show will also pay homage to Warhol’s trailblazing exhibition design, which De Salvo calls “extraordinary for its time” and which, like his artworks, has had a major impact on generations of artists. Warhol gleaned from the fashion world that making a product wasn’t enough: Its “retail” presentation had to catch the “consumer’s” eye. “Part of Warhol’s genius,” says De Salvo, “was having one foot in the commercial world and one in the history of art.”

Recommended: Andy Warhol Paintings Transform this Eclectic Long Island Home

Tongue firmly planted in cheek, Warhol mounted the 1969 exhibition “Raid the Icebox,” for which he mined the Rhode Island School of Design’s collection of American paintings and decorative objects but upended the typical artwork-as-revered-object approach: He re-created the arrangement of the works as they had been found in storage, leaving items in crates, racks, and bundles. “Now you wouldn’t think twice if an artist did that,” says De Salvo. “But it was pretty radical.”

In another show, Warhol stood his Campbell’s Soup Cans on a ledge around the gallery’s perimeter, mimicking grocery shelves. “Instead of it looking like a singular masterpiece,” De Salvo says, “he turned it on its head.”

Warhol’s interest in the full surround sometimes played into the creation of the artwork itself. For his epic 1978 series of “Shadow” paintings, a commission for the Dia Art Foundation, Warhol created 102 canvases to encircle the room. Based on one photographic image, setting vibrant colors dramatically against black, the enigmatic series is also his most abstract.

Recommended: A Jean-Michel Basquiat Musical Is Headed for Broadway

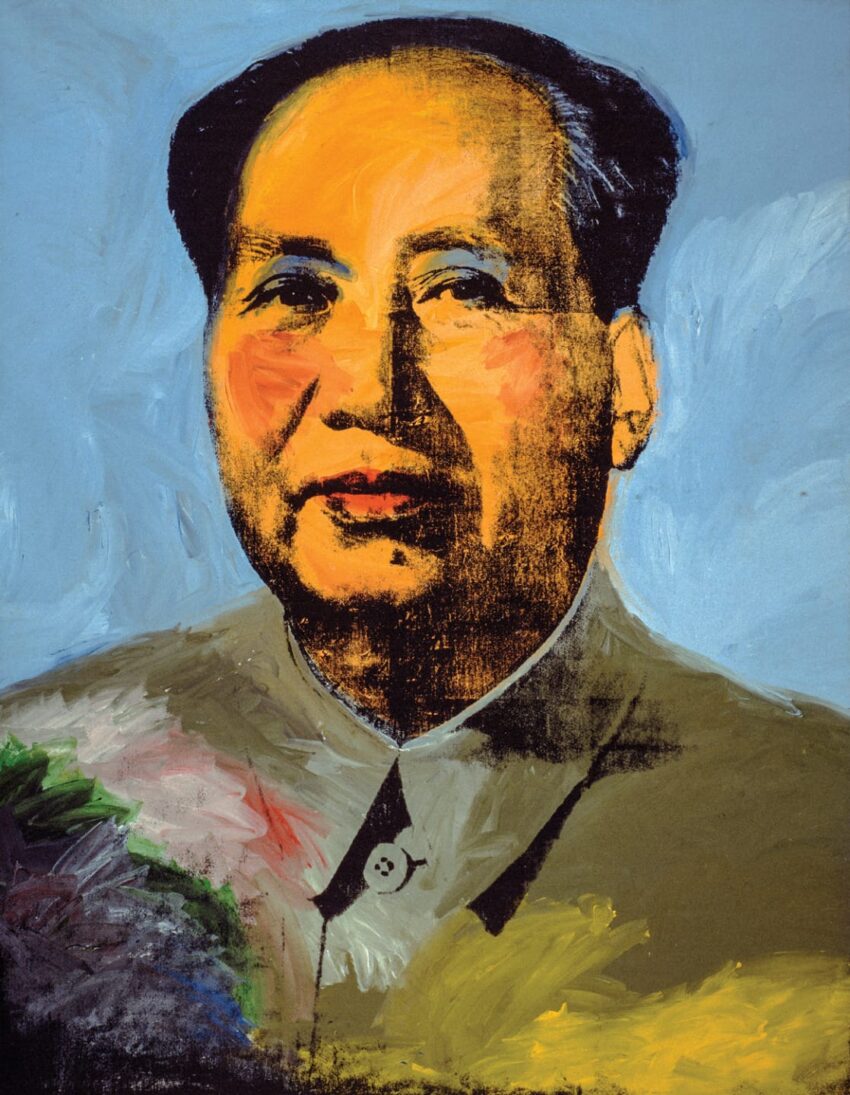

The retrospective will also attempt some myth-busting, aided by Warhol’s ample documentary videos. Some record his work process at the Factory, including a 30-minute session of putting a brush to a Mao canvas. “It punctures the belief that Warhol did not know how to draw or paint,” says De Salvo. “It’s a very insider look.” Other videos are intimate. One poignant clip depicts a “tender exchange between him and his mother. She’s lying in bed, and they’re speaking in Czech. It’s a very private moment.”

The devoted son is a side of the artist that doesn’t fit neatly into his (self-generated) larger-than-life persona. The same for his Catholicism. Many friends were not aware that the openly gay Warhol attended mass. “In a funny way, it would have been bad for his image,” says De Salvo. “There was something there that was extremely complicated.”

Warhol, after all, was a master of contradictions. While much has been made about some of the gay imagery in the show, De Salvo argues that it is far more subtle and conservative than, say, his contemporary Robert Mapplethorpe’s photography. “There’s a good boy in there,” says De Salvo. “There’s a lot of guilt.”

Warhol was 58 when he died unexpectedly in 1987, leaving one question maddeningly unanswerable: What would he have achieved had he lived?

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2018 Fall Issue under the headline Factory Original. Subscribe to the magazine.