The 5 Most Talked-About Pavilions at the 58th Venice Biennale

From Laure Prouvost’s tunnel to the fake beach at the Lithuanian Pavilion, here are the exhibitions getting all the buzz

The 58th Venice Biennale, titled “May You Live in Interesting Times” and curated by Ralph Rugoff, opens to the public Saturday, May 11. In the preview days leading up to the opening, visitors have been robustly speculating on this year’s winner of the prestigious Golden Lion, which is awarded to the national pavilion with the most compelling exhibition. (The previous award went to Anne Imhof at the German Pavilion.) While the jury is still out—the announcement will be made at a press conference on Saturday—several national representations are already getting tons of buzz—not to mention hours-long lines to get in. Here are the five most talked-about pavilions at this year’s Venice Biennale, in no particular order.

1. Ghanaian Pavilion

Ghana Freedom: El Anatsui, Ibrahim Mahama, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Felicia Abban, John Akomfrah, and Selasi Awusi Sosu

This is Ghana’s first time participating in the Venice Biennale with a national pavilion. To match the momentous occasion, it enlisted a star-studded group to collaborate, including the late Okwui Enwezor as strategic advisor, and David Adjaye as the exhibition’s architect. Curated by art historian and writer Nana Oforiatta Ayim, the museum-quality show is titled “Ghana Freedom,” after the song composed to celebrate the new nation’s independence in 1957.

Works by six artists representing three generations are shown in individual yet interconnected spaces, and all but one historical position are newly commissioned: El Anatsui’s massive tapestries of cast-off materials are draped over the walls of the medieval dockyards of the Arsenale. Ibrahim Mahama’s sculptural installation—consisting of wood, cloth, and smoked fish mesh—resembles a dilapidated library and emits a scent of burned organic matter.

Recommended: Galerie’s Guide to the 58th Venice Biennale

There are new paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye set in dialogue with studio photographs of women from the 1960s and ’70s by Felicia Abban, Ghana’s most prominent professional photographer. The third pairing is between celebrated video artist John Akomfrah, who created a three-channel video installation, and artist Selasi Awusi Sosu’s video sculpture, with both artists considering the violence and losses—of life, nature, industry—suffered in the West African country.

2. French Pavilion

Deep Sea Blue Surrounding You: Laure Prouvost

Known for her bending of language and slippery use of puns, the French artist, who lived in London for nearly two decades and won the 2013 Turner Prize, comments on the absurdity of national borders in her biennial installation. But she doesn’t do it with wordplay this time. Rather, she created a literal tunnel dug from the back of the French Pavilion, which aims to connect it to its neighbor, the British Pavilion. (She hasn’t yet succeeded in connecting the two.)

A meandering path, which leads viewers from the back door to the main gallery, is populated by sculptural pieces. Some are rendered in Murano glass and resemble fantasy water creatures. But there’s also debris, cigarette butts, and random e-junk—such as old cell phones—dotting the path. An eccentric film at the core of the installation shows a diverse cast of characters speaking in different languages. They embark on a road trip from the outskirts of Paris to Venice, although the destination itself is rather secondary; it’s the ideal of a fluid, global identity that’s the goal.

3. Brazilian Pavilion

Swinguerra: Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca

With the exhibition “Swinguerra,” the Brazilian-German artist duo Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca fill the pavilion with a stunning video and photo installation based on the titular style of dancing, often performed in large formations, which takes its cues from ballroom voguing, samba, and square dancing. For marginalized youth in Brazil, these types of get-togethers serve as formative social experiences:

Many of the young dancers featured here are black and of nonbinary gender. The sexually offensive lyrics of the music they perform to is translated from the local slang it’s sung in, such that the text on the screen of the two-channel video installation accompanies the fit bodies performing hypersexualized dance movements. This pairing creates enthralling moments that raise questions about performing gender stereotypes, and society’s acceptance of certain types of violent machismo into the mainstream, while rejecting harmless otherness.

4. Lithuanian Pavilion

Sun & Sea (Marina): Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė

Off the beaten track but worth the trip, the Lithuanian Pavilion features a vibrant nine-hour opera by director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, writer Vaiva Grainytė, and composer Lina Lapelytė.

Titled Sun & Sea (Marina), the durational performance takes place on an artificial beach installed inside a disused military building and features over 20 singers and actors clad in swimsuits lazily sprawled on beach towels under heaters. Visitors can climb to the mezzanine to view the scene from above.

The leisurely view of a day at the beach is pleasant at first but quickly becomes disturbing: Will a near-future eco-catastrophe mean that all of us would soon be frequenting artificial beaches, as the natural ones will be too polluted and toxic? Listen carefully and you’ll notice the libretto oscillates between soothing wave sounds to climate change stories and poppy melodies imagining the last day on Earth.

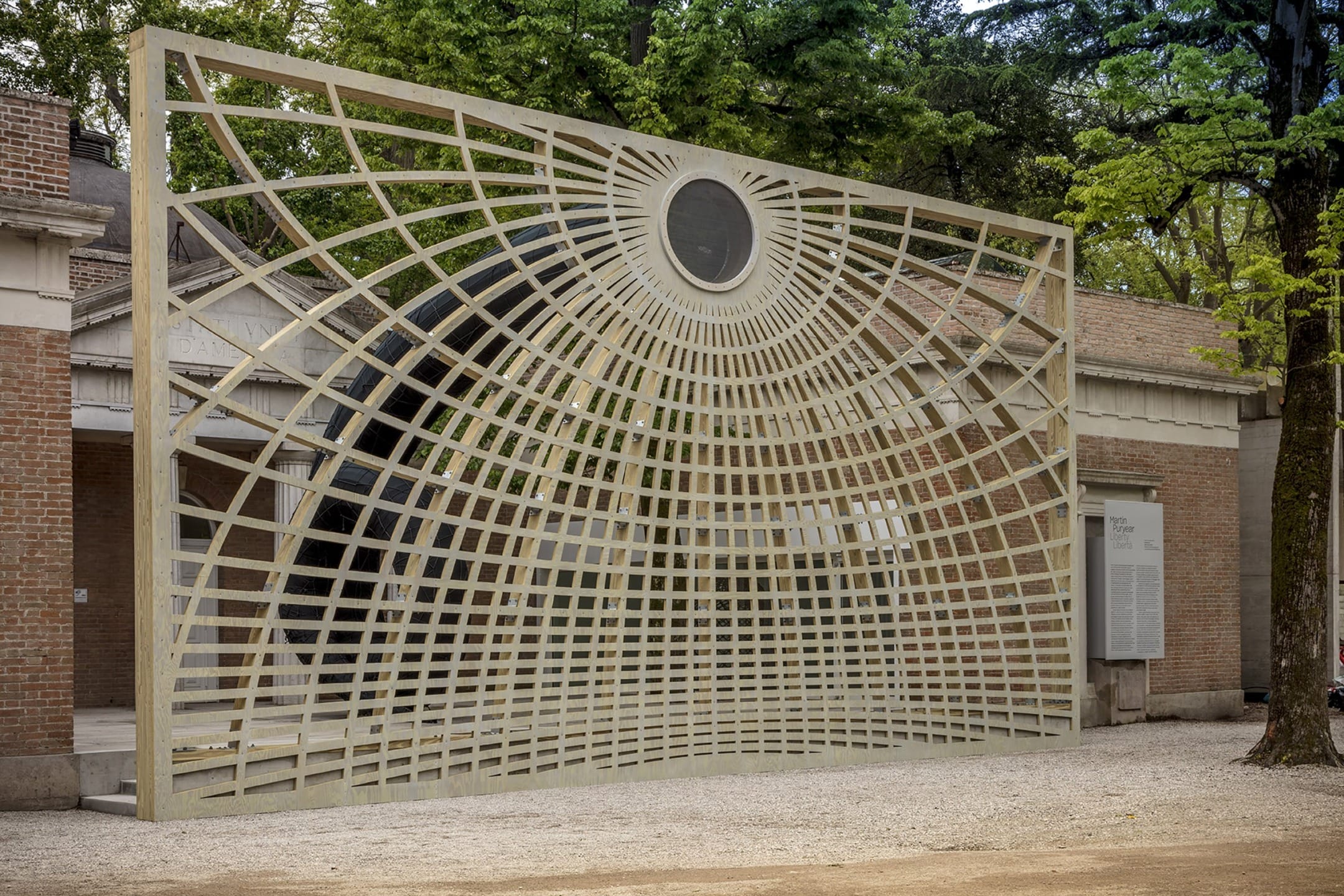

5. U.S. Pavilion

Liberty/Libertá: Martin Puryear

Martin Puryear large-scale yet pared-back sculptures make for a serenely powerful, symbolically charged exhibition inside and outside the U.S. Pavilion. At its core, a site-specific sculpture in the pavilion’s rotunda, A Column for Sally Hemings, is dedicated to the African-American slave owned by Thomas Jefferson who gave birth to four of his children. The red-painted cedar sculpture Big Phrygian resembles the cap that came to symbolize the French Revolution; in an opposite room, the sculpture Tabernacle is reminiscent of a soldier’s cap from the American Civil War. Its interior is lined with patterned fabric, like wallpaper, and through an opening, a round, shiny sphere resembles an eyeball staring back at the viewer. It’s a quietly political exhibition as a retort to loud and turbulent times, drawing a line between America’s history and its present.