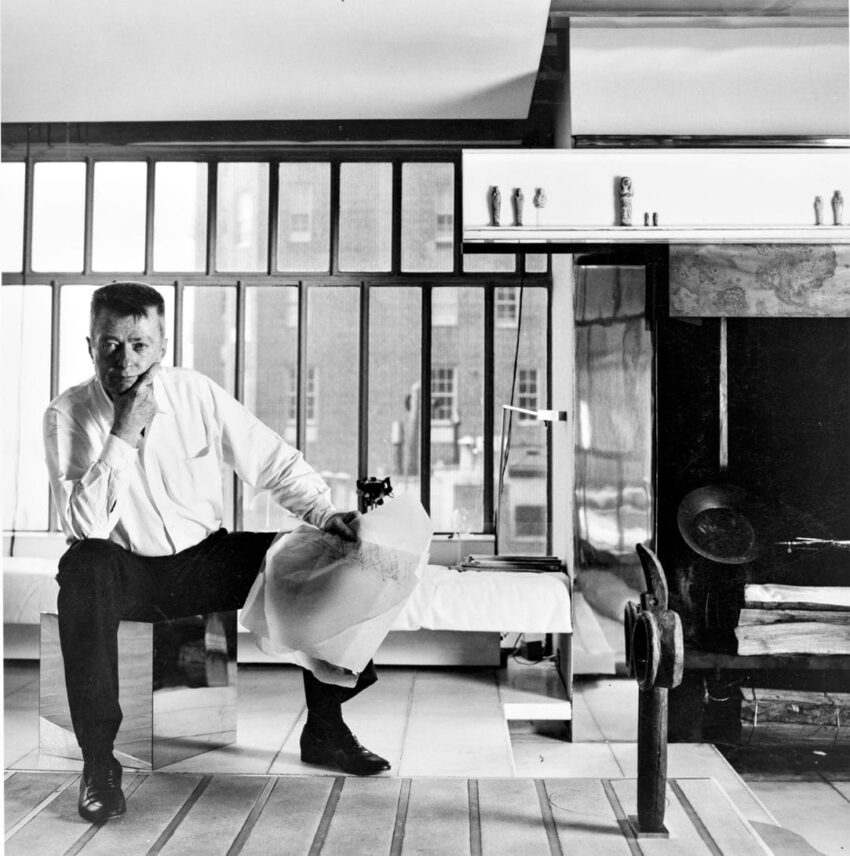

Paul Rudolph’s Legacy Lives on Through His Outstanding Buildings

The famed architect, who would have turned 100 this year, designed intricate brutalist structures that were all about performance

Paul Rudolph would be 100 this year. It’s tantalizing to imagine what his architecture would have been like had he lived into the digital age. With a pencil and a T-square, Rudolph, who died in 1997, was able to design buildings of stunning complexity. His Yale School of Art and Architecture, for example, conceals some 37 levels behind a seven-story façade. Its exterior is made of corduroy concrete, a hallmark of the style known as Brutalism, of which Rudolph was perhaps the greatest practitioner. But without sacrificing his predilection for architectural rigor, he was also able to create houses that embodied the optimism, and even the glamour, of the postwar era.

Recommended: How Architect John Murray Creates His Timeless Aesthetic

Rudolph’s Halston House, named for its most famous owner, glares at Manhattan’s East 63rd Street through an exterior of black steel and glass; inside, a floor-through living room is surmounted by a featherweight platform, ostensibly a link to the upstairs bedrooms but really a stage for its denizens to strut across. Steven Harris, who renovated another Rudolph house in New York, observes that the level changes served a social purpose: “In most cases, you entered rooms slightly above where you ended up. It let you make an entrance—his architecture is all about performance.”

Another domestic triumph is a sprawling house in Fort Worth, Texas, commissioned by Anne and Sid Bass. A kind of high-tech aerie of white steel and glass, it cantilevers over the soft green carpet of manicured lawns in thrilling juxtaposition.

Recommended: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Barton House Opens to the Public

Born in Kentucky, Rudolph began his career on the west coast of Florida, where he championed a style of architecture that blended interiors and exteriors with the help of unprecedentedly light structures and became known as the Sarasota School.

While one Florida creation, the Cocoon House, is being restored by the Sarasota Architecture Foundation, not all of his buildings have been so lucky. A government office complex in Goshen, New York, a kind of sandcastle of poured concrete and one of his most delicate creations, was renovated into oblivion last year. Other Rudolph buildings are likewise endangered. Two that seem secure for now, both in Manhattan, are the house he designed for himself on Beekman Place and a small multiuse building that incorporates a showroom for Modulightor, a lighting company that markets Rudolph’s innovative fixtures. That building, a compelling presence at 246 East 58th Street, is host to private tours. Rudolph isn’t around to play guide, but with his ideas bursting out in every direction, he almost doesn’t have to.

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2018 Fall Issue under the headline Performance Space. Subscribe to the magazine.