Artist Etel Adnan Makes Her Solo Debut at an American Museum

The show interweaves Adnan's charged poetry and her vibrantly colored abstractions

Etel Adnan may be best known as a novelist, poet, essayist, and playwright who captured the horrors of war and the tragedy of exile, but in fact, the 93-year-old Lebanese-American is that rare creative talent who also paints in oil and watercolor (and designs tapestries) while still managing not to come off as a dilettante.

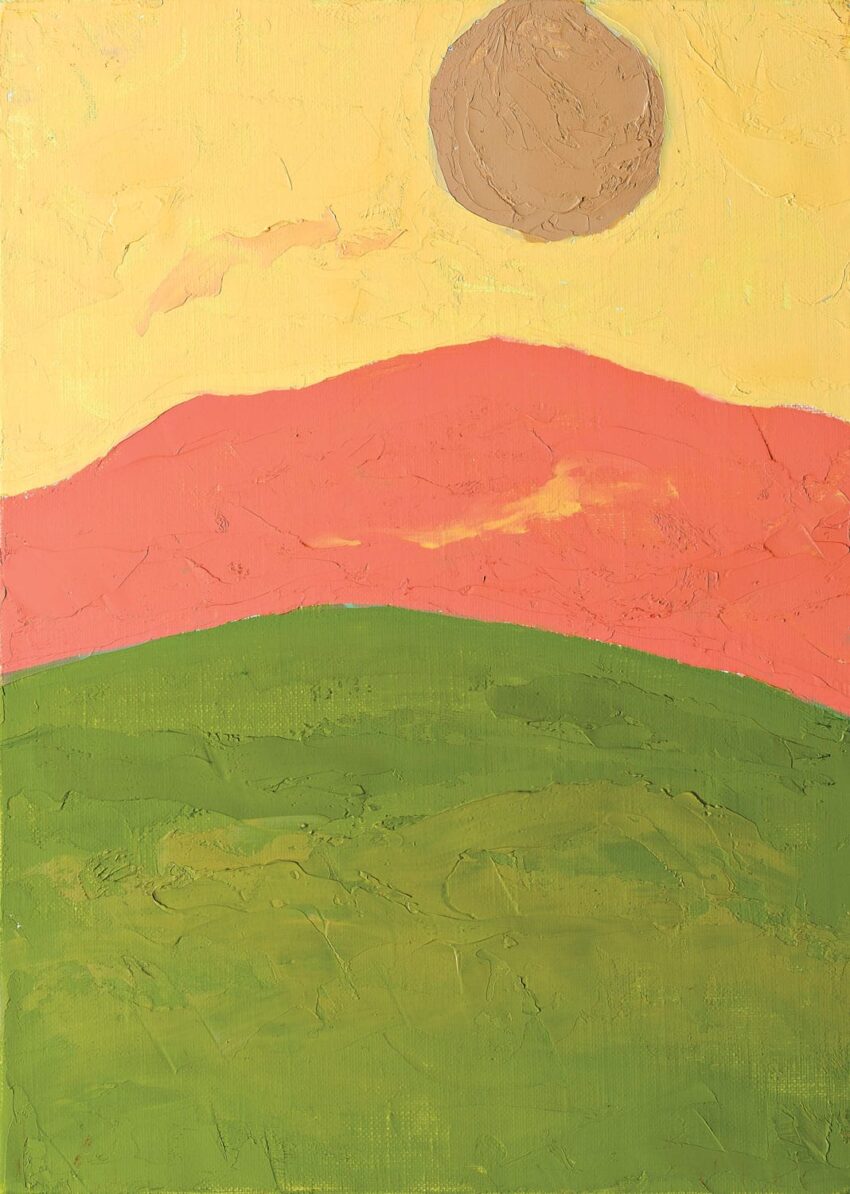

Her exhibition, “A Yellow Sun a Green Sun a Yellow Sun a Red Sun a Blue Sun,” which opened in May and runs through December at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA), interweaves her charged poetry and her vibrantly colored, sparely composed abstractions. The show is Adnan’s first solo exhibition in an American museum.

Recommended: Robert Wilson’s Summer Home Is Just How You Would Imagine

“She makes a clear distinction between how she approaches writing and how she approaches painting,” says the show’s curator, Elise Chagas, a second-year graduate student in art history at nearby Williams College. “Her writing is historical and specific, where she is raging against the world. Her painting is an expression of pure joy.” Or as Adnan once said, “It seems to me that I write what I see, paint what I am.”

Even so, Adnan has also found ways to juxtapose text and image. Her acclaimed book-length poem The Arab Apocalypse, about the Lebanese Civil War, which displaced nearly a million people from 1975 to 1990, is peppered with drawings that evoke explosions and were produced contemporaneously with the poetry, not as an afterthought. Her leporellos, accordion-like books, similarly blend words and visual imagery.

Recommended: Why the Berkshires Are This Summer’s Cultural Hot Spot

Born in Beirut in 1925 and raised among the French-speaking elite, Adnan studied at the Sorbonne, the University of California, Berkeley, and Harvard before teaching philosophy in Northern California. She began painting in 1958 and has long adhered to a strict routine: She places a small canvas flat on a table and applies paint with a palette knife, not a brush, always completing a canvas in one sitting. In Chagas’s view, this process is less rules-based—à la Sol LeWitt and other Conceptual artists—and more a kind of habit. “She’s interested in creating as direct a channel as possible from vision to canvas,” Chagas says. “I think that’s why she does them quickly.”

While Monet had his gardens at Giverny, for some 50 years Adnan has painted Mount Tamalpais, which she could see from her house in Sausalito, California. Even in recent years, living primarily in Paris, she has painted the peak from memory. Season after season, year after year, in thick swipes of pigment squeezed straight from the tube, she has repeatedly rendered the mountain, a dominant triangle in almost childlike landscapes of simple, flat shapes and bright colors.

For years, Adnan renounced the French language of her youth as a tool of colonialism, weaponized to eradicate Arab culture. Instead, she wrote in English. Although she eventually found her way back to French, painting provided a way to transcend language. “I didn’t need to write in French anymore,” Adnan declared. “I was going to paint in Arabic.”

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2018 Summer Issue under the headline Creative Edge. Subscribe to the magazine.