Why Provocative Artist David Wojnarowicz Is More Relevant Than Ever

A pair of fascinating new exhibitions shed light on his daring approach

One of the most striking pieces in “David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night,

an exhibition on view at the Whitney Museum, is Globe of the United States (1990). The work, as the title suggests, consists of a globe that Wojnarowicz illuminated with an interior lightbulb and reworked externally with black acrylic paint so that instead of continents, it depicts nothing but the outline of the United States, repeated dozens of times. The result is striking and while made nearly 30 years ago, it still resonates in today’s political climate.

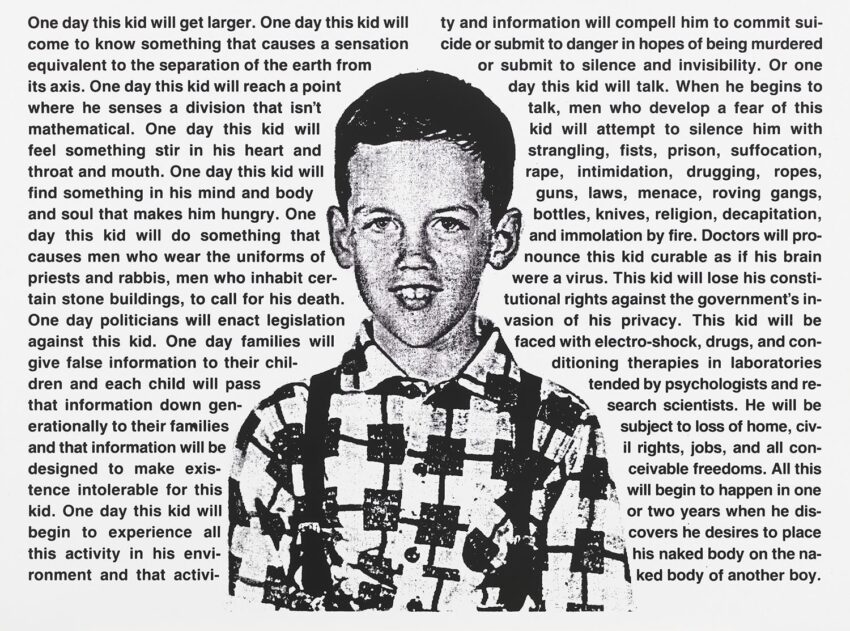

During his career, Wojnarowicz wasn’t shy about his political leanings, his sexual preferences, or his anger. A multimedia queer artist who was once in a punk band, he used spoken word, painting, photography, writing, and film to make work that addressed issues both personal and bureaucratic. However, his life was cut short after he was diagnosed with HIV in 1987. He died in 1992 from an AIDS-related illness at 37 years old.

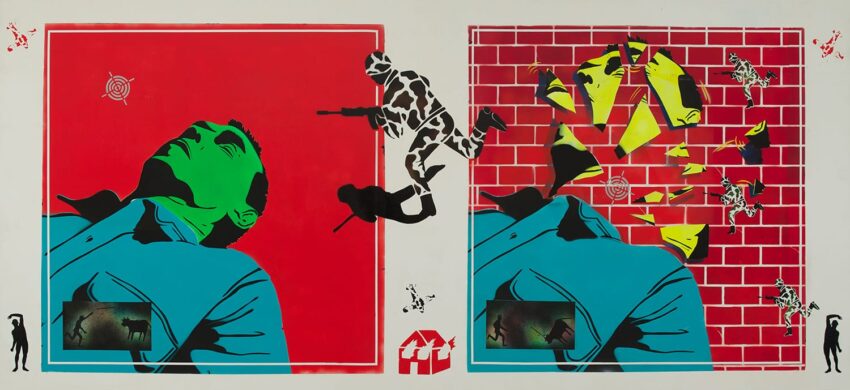

In the survey at the Whitney, co-curators David Kiehl and David Breslin, showcase Wojnarowicz’s artistic trajectory in a nearly perfect chronology. As viewers, we are invited to follow him on his journey: a man at odds with himself, religion, and the love he craved. An aura of moral and emotional tension hangs heavily in each gallery, especially felt in several untitled paintings from the mid-1980s. Using bold colors, graphic shapes, and layered narratives, they reveal his own struggle with sexual exhibitionism through the filter of religion—one that both intrigued and angered him.

Recommended: We Go Inside the Studio of Sean Scully Ahead of His Hirshhorn Show

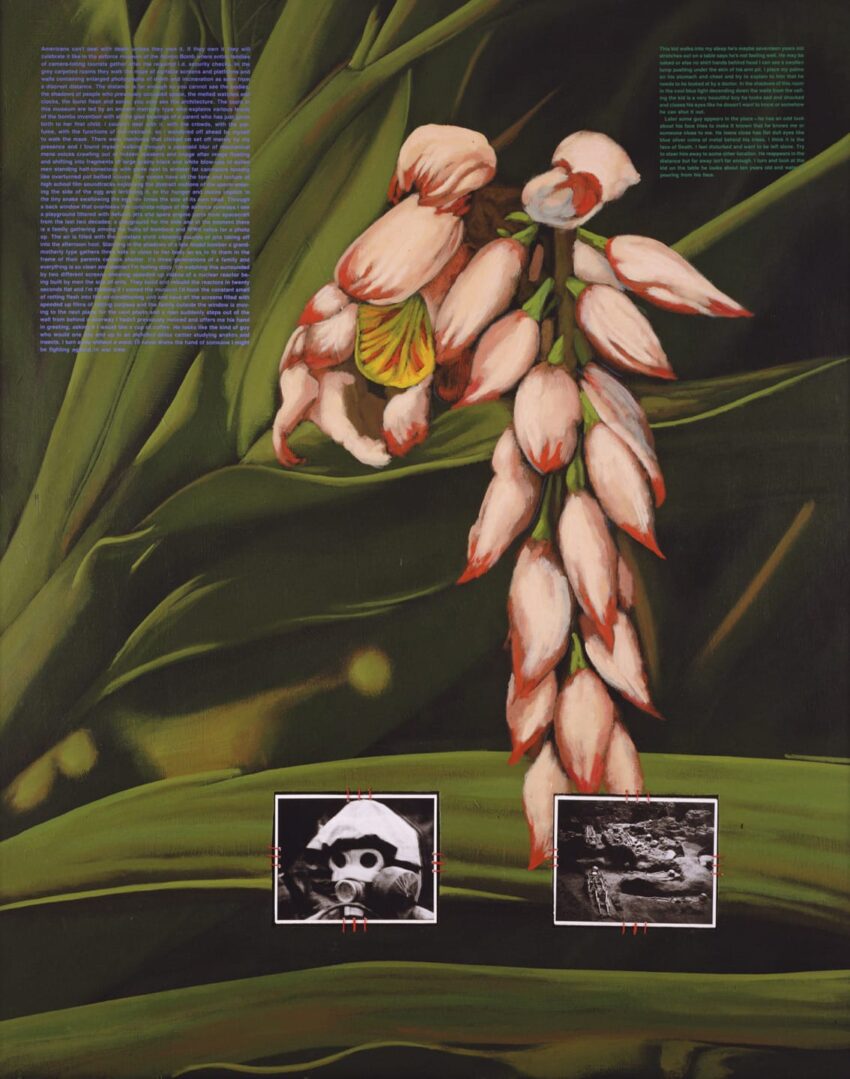

In a recent discussion at PPOW Gallery—currently exhibiting installations by Wojnarowicz, timed with the Whitney show—artist Karen Finley and culture critics Carlo McCormick and Cynthia Carr spoke candidly about the late artist, their mutual friendships, and what McCormick described as a “beautiful contradiction.” Wojnarowicz didn’t shy away from conviction.

“He had such a strong sense of purpose and knew when he had to fight or take action,” said Finely, a performance artist who collaborated with Wojnarowicz, in the short film, “You Killed Me First,” which was directed by Richard Kern and is on view at PPOW. “He made artwork as a way to process all that he was going through. It was a form of evidence and witness of a particular story, and having the strength to speak.”

During Wojnarowicz’s lifetime, he used art as a sounding board, silently echoing his and so many others experiences at the time including those of indifference and cruelty. His pending death prompted a particular level of urgency, which is evident through his extensive oeuvre. He addressed homophobia and his own mortality, in shocking and impactful ways.

“David felt that he had a duty to represent and to create work that was expressing queerness,” said Finley.

When so much in our world now can appear vapid and stripped of emotional engagement, looking at David Wojnarowicz’s work functions as a reminder of the role of honest communicator, risk-taker, and activist. Along with “You Killed Me First” a low-budget horror film, filled with gore, Wojnarowicz often attracted controversy, specifically from right-wing conservatives.

Recommended: 7 Incredible Public Artworks to See in New York This Summer

One of his most well-known and eyebrow raising efforts is the silent film “A Fire in My Belly” (1986-87) which has, since its creation, been censored numerous times. Visitors may or may not see the film during their visit to the Whitney due to the fact that it loops in a sequence and is not a focal point, and rightly so.

Rather than focus on the most controversial aspects of his practices, the Whitney instead allows for his memory and fingerprint to shine with grace. It’s an honest and thoughtful portrait of a man who expressed his inner turmoil, outwardly.

Carlo McCormick, who has written academic texts about Wojnarowicz, was one of the first to work with the late artist in an exhibition titled The Nuclear Family, a second iteration of which included Marilyn Minter. “We tend to talk about AIDS in the past tense although there are so many people still dying from it,” said McCormick, “and thankfully, people still living with it which was not an option then.” He added, “In my very early engagement with him, I had the feeling he was speaking for all the marginalized and so many others, his voice the presence of the collective.”

The exhibition “David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night” is on view at the Whitney Museum through September 30, 2018. The installations on view at PPOW titled, “Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins: The Installations of David Wojnarowicz,” are on view through August 24, 2018.