How Artist Brian Clarke Is Pushing the Medium of Stained Glass

Ahead of his show at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design, the artist invites Galerie into his London studio

If Brian Clarke has his way, visitors to a new exhibition of his work at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design this spring will leave with certain assumptions bent out of shape. Clarke is known for his work in stained glass, but more important, he makes technically and conceptually brilliant art that challenges this form’s place in the creative hierarchy. “Skilled craft is an entirely legitimate position to take when you look at the medium,” he says, “but what’s really significant about stained glass is that it’s at the highest level of poetic achievement.”

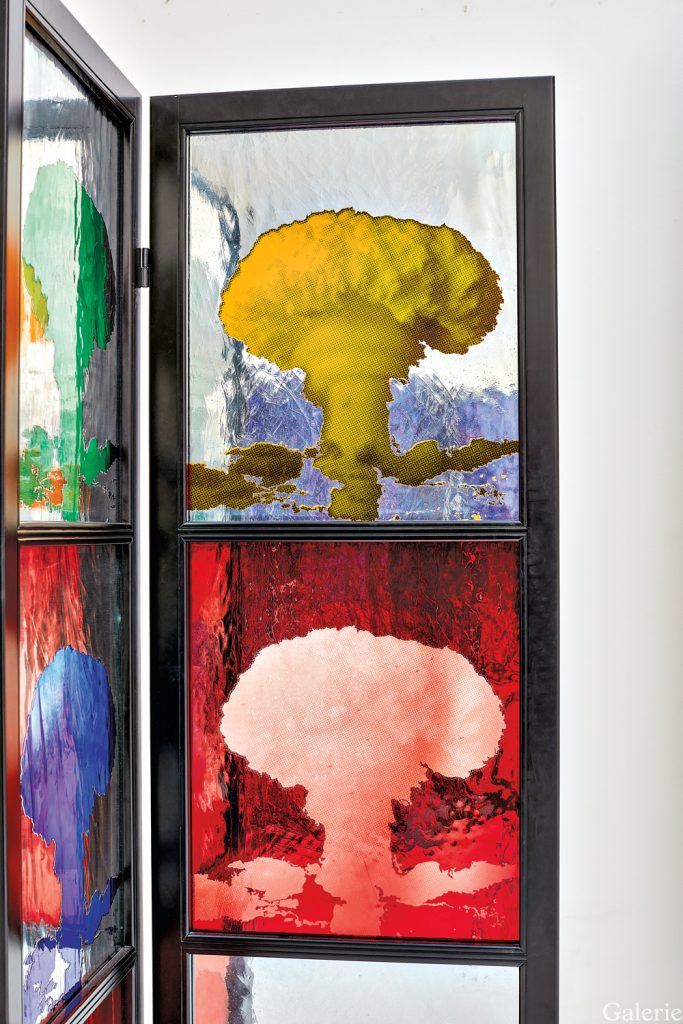

That might sound a little arch—until, that is, you enter a room filled with Clarke’s glass screens, where colors seep across the landscape, washing the space with liquid patterns and hues. “Painting is viewed by the light reflecting off it. Glass has light passing through it, so it’s in a continual state of flux, and the effect becomes volumetric,” says Clarke. “It depends on what is happening around it. It’s a peculiar link between the external and internal.”

Clarke, now more productive than ever, gravitated to stained glass in his late teens, when his then girlfriend, a clergyman’s daughter, exposed him to an awe-inspiring church window installation. He went on to study the technique at an art school near his home in the north of England before embarking on a party life in London in the early 1980s. “It was a brief period, that arty-party one, but it seems to chase me around,” he laughs.

Recommended: Inside Bernard Frize’s Minimalist Studio in Berlin

It included celebrities like the Stones and the Beatles, though friendships with architects such as Zaha Hadid and Norman Foster may have been his most productive. “The minute I met Norman, we never stopped talking,” says Clarke. He collaborated with the architect to create a vast glass wall for Foster’s Al Faisaliah Center skyscraper in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, which opened in 2000. “It’s like a mirage, with a great diversity of imagery,” says Clarke of the installation. “There were all sorts of matrices, with fish moving through water and birds flying in the air. It’s like cinema, really.”

The synthesis of art and architecture, of bringing drama and color into daily life, is an ideology he holds very dear. In his vast personal collection of historical stained glass is a maquette of the Modulor Man, designed in the early ’50s by Le Corbusier for the Cité Radieuse in Marseille, France. “It’s been really handled,” says Clarke. “You can see how they’ve gone through the fenestration.”

At MAD, Clarke’s liberal range of subject matter will be laid bare, from the flamboyant blooms that he loves to make—including Flowers for Zaha, a posthumous homage from 2016—to the artist’s rather darker reaches. In Manhattan (2018), a dozen pink atomic bomb clouds explode in their individual frames; elsewhere, a roll call of famous architects are line-drawn as skulls in scintillating liquid lead on solid lead grounds. All push at the edges of technology and possibility. It’s not at all what you might expect, on many levels. But then, as Clarke says, “I’m not really known for my saints.”

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2020 Spring Issue under the headline “Leading Light.” Subscribe to the magazine.