Pioneering Collective AfriCOBRA Spotlighted at Art Basel

The groundbreaking movement is marking its 50th anniversary with exhibitions at MOCA North Miami, Brooklyn Museum, and Tate Modern

Although the African-American artist collective AfriCOBRA was born out of the civil unrest of the late 1960s, the group feels just as poignant today. As it celebrates its 50th anniversary, paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media pieces by its founders—and others who joined later—have been headlining gallery shows, including ones at Kavi Gupta in Chicago and Kravets Wehby in New York. They’re also being incorporated into groundbreaking group exhibitions, such as “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” which originated at Tate Modern and is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through February 3.

“AfriCOBRA was a response not only to the political climate of the Black Power movement, but also thinking about how artists—black artists—could participate in a time of struggle and liberation in the United States,” says Jeffreen M. Hayes, curator of “AfriCOBRA: Messages to the People,” which is currently on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami and kicks off with an artists’ reception during Art Basel in Miami Beach.

Recommended: 16 Buzzworthy Artists to Watch at Art Basel, Untitled, and NADA in Miami

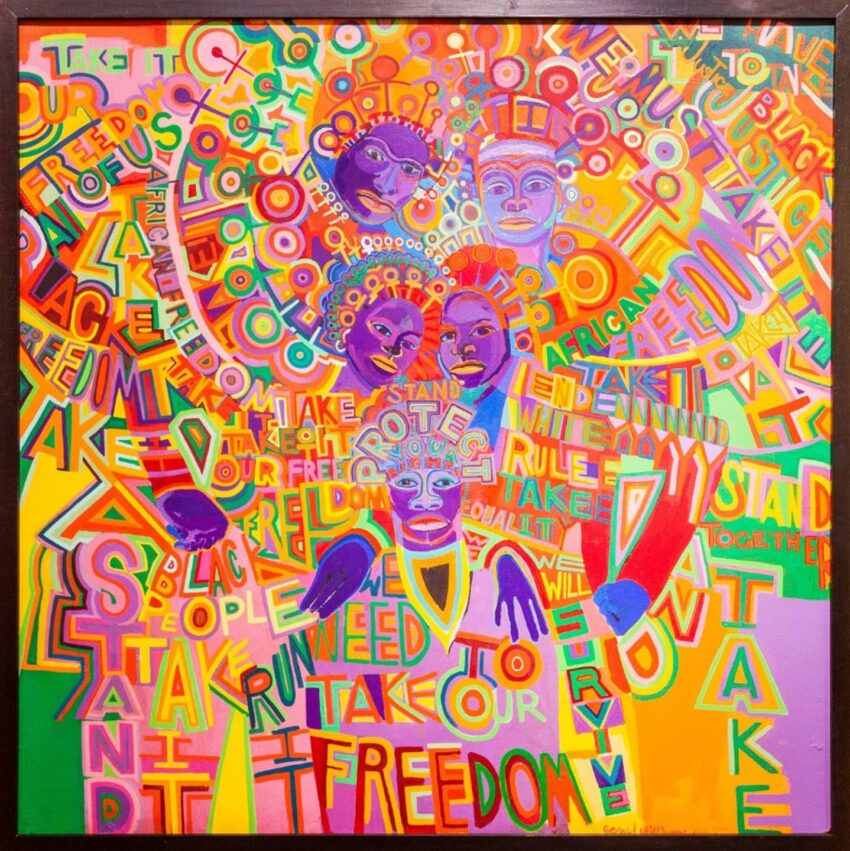

Cofounded in 1968 by the late artist Jeff Donaldson alongside talents Jae Jarrell, Wadsworth Jarrell, Barbara Jones-Hogu, and Gerald Williams, AfriCOBRA embraced what it called “coolade colors”—vibrant and hypersaturated shades of orange, strawberry, cherry, lemon, lime, and grape—as celebratory statements of black culture. The group, whose moniker is short for African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists, took on Donaldson’s 1969 essay, “10 in Search of a Nation,” as its manifesto: “Color that is expressively awesome. Color that defines, identifies, and directs. Superreal color for Superreal images.”

Its aesthetic philosophy centered on exalting the black experience, employing references to African national and traditional symbols in syncopated, kaleidoscopic rhythms. Donaldson called the style “TransAfrican” and defined it as “superreal”—art that exceeded reality.

Recommended: Still the Main Attraction, Art Basel Returns to Miami Beach

AfriCOBRA arrived when black artists were systematically being denied access to the greater art world and there was little institutional support for people of color; museums, still very Eurocentric, rarely showed black artists, nor did they hire black curators or critics. The collective’s depictions of black subjects in moments of triumph, or “shine,” were images that institutions had so far failed to show. “They themselves became a kind mini-institution,” says Hayes of AfriCOBRA.

At the MOCA North Miami exhibition, on view until April 7, works of the founding members are presented alongside projects by artists who later joined the group, including Nelson Stevens, Napoleon Jones-Henderson, Omar Lama, Sherman Beck, and Carolyn Lawrence. On display are pieces that focus on the black family, an early theme central to the artists’ work. “They decided what they could contribute was a visual aesthetic,” says Hayes, “not just for the late 1960s into the early ’70s, but into contemporary times.”

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2018 Winter Issue under the headline Color Form. Subscribe to the magazine.