How Joana Vasconcelos’s Feminist Work Is Redefining Art History

The Portuguese artist's feminist conceptual art, on view at the Guggenheim Bilbao, holds its own with Koons and Hirst

The bulbous and billowing metal behemoth that is the Guggenheim Bilbao is more than just an architectural landmark. Designed by famed architect Frank Gehry in 1997, the Spanish museum’s now-iconic profile—accompanied, as it is, by Jeff Koons’s towering 43-foot topiary puppy—is a veritable testament to the bravado of many a male artist. But Joana Vasconcelos is beating these boys at their own big game in “I’m Your Mirror,” a retrospective featuring 30 large-scale works spanning the Portuguese artist’s meteoric 25-year career, on view through November 11.

Best known for her outsized, tongue-in-cheek sculptural installations, the 46-year-old artist often humorously takes on issues ranging from gender identity to consumerism. “Joana has always explored notions of femininity, and she refers in her work both to the intimate sphere and the public presence of women in contemporary society,” says Guggenheim Bilbao chief curator and conservator Petra Joos, who organized the exhibition with independent curator Enrique Juncosa.

Though Vasconcelos had consistently been making work since the mid-1990s, it wasn’t until the 2005 Venice Biennale that she found herself catapulted to fame after she showed an 18th century–inspired candelabra made of thousands of unused tampons. Titled The Bride, it was hailed as a work of readymade genius that stood up to the male-dominated history of conceptual sculpture and installation founded by the likes of Marcel Duchamp and continued by contemporary market heavyweights like Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, and Takashi Murakami.

Recommended: Takashi Murakami Brings Cuteness and Catastrophe to Russia

With that, Vasconcelos had made her mark and she became the third artist—after Koons and Murakami, in fact—to be invited to take over Paris’s Palace of Versailles in 2013. She was the first woman to ever be bestowed the honor and profile of such a commission, but the show was met with mixed reviews. It was both acclaimed and derided for its bombastic kitschiness, as seen in works like Marilyn (2011), a human-scale stiletto made of stainless steel pots and pans.

Although “I’m Your Mirror” features both The Bride and Marilyn, Joos and Juncosa don’t make them out as monumental highlights of Vasconcelos’s career—even if they garnered the most attention. Instead, they posit them within a much larger and longer trajectory of amusing social commentary and acerbic self-reflection within the artist’s career. They are gathered together in the show’s largest gallery with several other works, both new and old, around one of the artist’s most recent pieces: A giant Venetian mask made up of overlapping baroque mirrors for which the show is named.

Because of its scale and the layering of its surfaces, it’s impossible to see more than a fragment of oneself or the gallery space. But this disjointed viewing experience is exactly what the artist was going for to underscore how her work is as much an amalgam of her life as it is what viewers choose to see in it.

“I wanted this piece to reflect my work over the years, but not without reflecting everyone else back with it,” Vasconcelos explains, adding that mask also references broader ideas of Lacan’s “gaze” as well as hidden feminine identities. This theme is reiterated in 2002’s contentiously received Burka, which sits adjacent to the mirrored mask in the Guggenheim’s gallery space. The piece is an amalgam of women’s dress fabrics, from lace to sari silks, stitched into a traditional Islamic head-to-toe female outer garment. It adorns a wrecking ball, one which drops loudly and violently at regular intervals, sending a vibratory jolt through the room.

Even 16 years later, the artist insists Burka is her most feminist piece to date. “It’s about the limitations put on female identity, but also how this loss of identity can offer safety, even power,” she says, noting that the erasure of identity markers like gender or race has the potential to topple discriminatory social and political practices.

Recommended: The Ultimate Art-Lover’s Guide to Lisbon

Yet Vasconcelos’s best manifestation of female-centered power in “I’m Your Mirror” is undoubtedly Egeria, the enormous, site-specific textile sculpture installed in the Guggenheim Bilbao’s atrium. It’s the latest and largest work to come out of her well-known and exceptionally colorful biomorphic series, “Valkyries,” named after the Norse female war goddesses who were said to decide who lived and died in a battle.

Writhing and rhizomatic, Egeria bursts into the axis of the atrium with a fire-colored bulb that hangs deep into the center of the building. Multi-hued tendrils spiral off of it at different angles, probing their way toward the staircases and hallways of Gehry’s sterile stainless steel edifice where they erupt in smaller nodules of varying colors, all softly blinking with embedded fairy lights, as if alive. Against the hard steel and cold glass of the Guggenheim Bilbao’s building, it’s unabashedly feminine in its bendy, jewel-toned, and bedazzled splendor. Perhaps even more so given it serves as celebration of the historically female-centric tradition of handicraft and textile work.

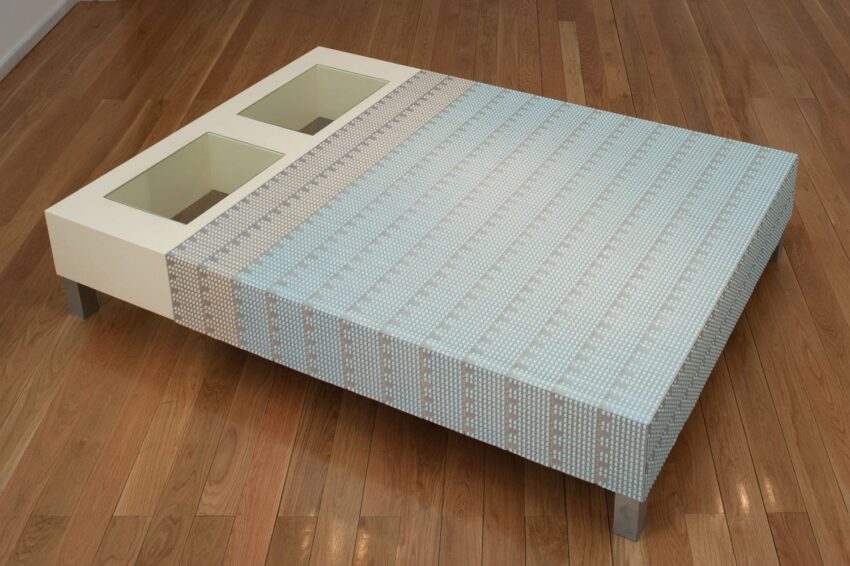

Full Steam Ahead (Red) [A Todo o Vapor (Vermelho)] #1/3, 2012 . Courtesy of the artist, Joana Vasconcelos, VEGAP, Bilbao, 2018

The massive installation comes on the heels of the museum’s survey of modernist textile artist Anni Albers last year. Indeed, “I’m Your Mirror” reflects the Guggenheim’s growing dedication to presenting the work of female artists on a grander scale, with former shows ranging from retrospectives dedicated to Louise Bourgeois to surveys of work by performance artist Esther Ferrer. And with Egeria, Vasconcelos proves she’s up for the monumental challenge to redefine the male-dominated history of art.

“She will surely be considered in the future a strong reference for female artists,” Joos says, “but hopefully, too, once equality between men and women will become a true reality, by all genders of artists.”