Go Inside the Former Home of Paul Cézanne in Aix-en-Provence This Summer

As part of the “Cézanne 2025” year-long celebrations, visitors have the rare chance to visit Bastide du Jas de Bouffan, the artist’s sprawling estate

“When you’re born there, you’re done for, there’s nowhere else that speaks to you more,” wrote Paul Cézanne to a friend, referring to his native city of Aix-en-Provence. Call it a grumbling avowal of love for the pine-covered countryside, rust rock quarries, blue skies and the limestone silhouette of Mont Sainte-Victoire. Reputedly timid, gruff, temperamental and eccentric, Cézanne tended to shun society, more at ease when hauling his easel up a hill alone in a forest than showing up at the Café Guerbois for lofty artistic discussions with his peers. No sooner would Cézanne arrive in Paris to show his work than “he’d start talking about returning to Aix,” noted his childhood friend, art critic and writer, Emile Zola with exasperation.

Surprisingly, during Cézanne’s lifetime (1839-1906) and for years to come, the city of Aix-en-Provence did little to recognize the misanthropic revolutionary painter (dubbed by Picasso as “the father of us all”) who followed his instincts and shook up the modern art world to its core. Now, more than 12 decades after his death, that’s about to change. Opening on June 28th, Aix will be celebrating its native son with a major retrospective, “Cézanne 2025” that features a program of exhibitions and events all over town.

One of the highly-anticipated spots to visit on the itinerary is the newly renovated Bastide du Jas de Bouffan, the Cézanne family’s 14-hectare estate where the painter intermittently lived and worked for nearly 40 years. When Louis-Auguste, Paul’s tyrannical banker father, purchased the sprawling eighteenth-century manor in 1859, it was meant to serve as a second home in Aix’s nearby countryside.

“At the time, there was nothing but farmland—olive and almond groves, chestnut trees, vineyards,” says Bruno Ely, historian and curator of the Musée Granet’s upcoming show, “Cézanne au Jas de Bouffan”—an allusion to the neighboring apartment buildings that block the once-pastoral view of Mont Sainte Victoire. Come summer, visitors can stroll through the lush replanted gardens and majestic tree-shaded walkways, lined with stone fountains, statues and blue-grey water basins, all recognizable in Cézanne’s works.

Add to that a major surprise. During the meticulous restoration of the interiors of the bastide—where 25-year-old Paul, a budding art student painted directly onto the curved plaster walls of the “Grand Salon”—workers hit on an unexpected find. A giant wall panel with five to six square-meter fragments of a ship entering a harbor, was buried under layers of paint; experts believe it’s an unknown piece of Paul’s early experimentations. “The panel may not be fundamental Cézanne’s body of work,” Ely concedes with a smile, “but who knows what else might be hidden in the house? It would have required an impossible budget to analyze every centimeter, but maybe one day we’ll stumble a forgotten sketch or drawing under the walls of his room.”

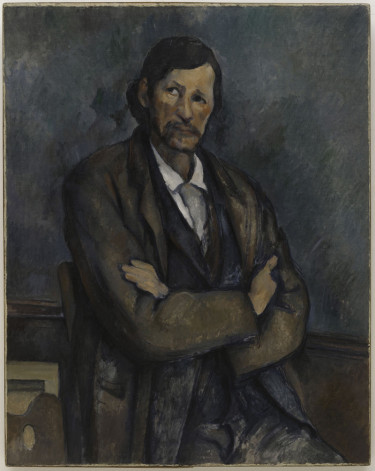

A wander through the atmospheric rooms of Jas de Bouffan conjure other possible connections to Cézanne’s inspiration. In the bedroom of Madame Cezanne, for example, you’ll see gypseries—ornate white sculpted stucco that adorned walls and chimneys in 18th century Provence—depicting a graceful Leda the Swan-like goddess who may have been the model for Cézanne’s mythological Bathers series. However, don’t expect a complete recreation of the family homestead. There were no photographs of the interiors of the house, which Paul and his sisters, Marie and Rose, were forced to sell in 1899, three years after Louis-Auguste’s death. “We don’t know how Jas de Bouffan was furnished, aside from an armchair or two in the portraits of Cézanne’s father and his friend Achille Emperaire,” adds Ely.

At the Musée Granet, the show will feature 130 drawings, oils and watercolors—some rarely seen and on international loan—that reflect the painter’s attachment to Provencal scenes from his beloved bastide. In addition to Cézanne’s most celebrated works, from still-lifes of fruit and landscapes to card players and portraits of family members, the exhibition also includes the artist’s youthful works (originally painted on the walls), such as his monumental interpretation of the Four Seasons in the style of Ingres.

Another highlight: six kilometers east from the center of Aix, down a narrow pine-shaded country road, there’s a new public trail that leads to the rugged golden rock Bibémus Quarries. It was here that Cézanne and Emile Zola once roamed in their boyhood, reciting romantic verse; the artist later returned and rented a tiny stone cabin where he could capture the intense luminosity and geometrical shapes of nature—red earth, green scrub, towering jagged boulders and, off in the distance, the ever-changing colors of Mont Sainte Victoire. Along with the guided walking tour, you’ll discover a dozen discreetly placed reproductions of the oils and watercolors, marking the precise spot where Cézanne planted his easel.

Cézanne’s last hilltop studio, Atelier des Lauves, which he acquired in 1901 and built according to his own plans, has been freshly renovated, offering a display of the personal objects—Provencal pottery, porcelain ginger jars, skulls, and cane chairs—that figure in his paintings.

“Will I achieve the goal I’ve been striving for all this time?” Cézanne wrote to his artist friend Émile Bernard in September 1906. A month later, while painting in the woods near his studio, Cézannne was caught in a storm, and brought back in a laundry cart, chilled to the bone. Already ill with diabetes, he died on October 22, 1906.

The joy of rediscovering Cézanne’s world close to home, both in museums and outdoors, may also shine a light on the artist’s unique creative process, which laid the foundations for Cubism. “I could paint for a hundred years, a thousand years without stopping” he once told his art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, “and I would still feel as though I knew nothing.”