Highlights of the 13th Dakar Biennial in Senegal

Africa’s oldest and largest biennial calls upon the continent’s artists to take action. Rebecca Anne Proctor reviews the biennale’s urgency for unity, locality and artistic recognition

Outside Dakar’s Palais de Justice, a large imposing modernist building by the sea, is a flimsy red house made from fabric. Held up by strings and a support linked to the nearby building, the house sways around in the wind as if dancing to soft background electronic music. This ethereal installation titled The Red House by Dominican artist Marcos Lora Read, is one of the highlights of the 13th Dakar Biennial in Africa, and symbolizes the sentiment of many of the artists in the exhibition: a longing for location, recognition, and unity.

The art biennial isn’t foreign to Africa, of course. There’s the Rencontres de la Photographie Africaine Biennale de Bamako (founded in 1993) in Mali or the Johannesburg Biennale, which witnessed just two editions in 1995 and 1997. At least 20 others including the Marrakech Biennale, Biennale de Lubumbashi, and la Biennale de Duta, have taken place over the last several decades. None, however, has been as successful and far reaching as the Dakar Biennale (also known as Dak’Art), founded during the 1990s.

Held under the patronage of the President of the Republic of Senegal, this year celebrates the event’s 26th anniversary and welcomes back Simon Njami, a Swiss national of Cameroonian descent, as the artistic director. Titled “A New Humanity,” the biennale’s main exhibition at the Palais de Justice features work by 75 artists from 35 countries around the world celebrating African art. Alongside Njami, Dak’Art has invited a handful of guest curators to present work in surrounding museums.

The Red Hour, an expression derived from Francophone Caribbean writer Aimé Césaire’s play “And the Dogs Went Silent” is about being ready for freedom. “I am the Red Hour, the undone hour, red,” says Njami in his introductory statement. “The Red Hour is the coming of age. It is the moment when one emancipates oneself from what has been by transforming it and giving it a new strength. It is the hour of metamorphosis and transformation.”

Africa’s age, it very much seems, is now. International interest in African art is exploding. There are now a several dedicated sales of African art at Sotheby’s and Bonhams, a boom in art fairs, such as the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, new museums such as Macaal in Marrakech and Zeitz MOCAA in Capetown, and major exhibitions like the MoMA’s “Bodys Isek Kingelez: City Dreams” (on view until 1 January 2019), its first ever solo show of a black African artist.

It’s now time for African artists to seize their chance, said Njami during the press conference. “Art is, without doubt, the domain through which things can be said which go well beyond the limits imposed by language.

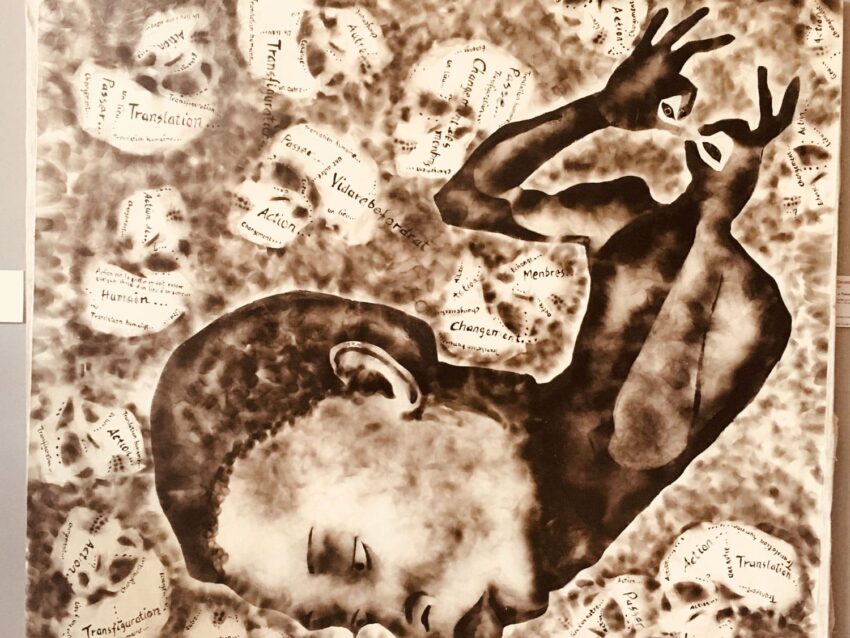

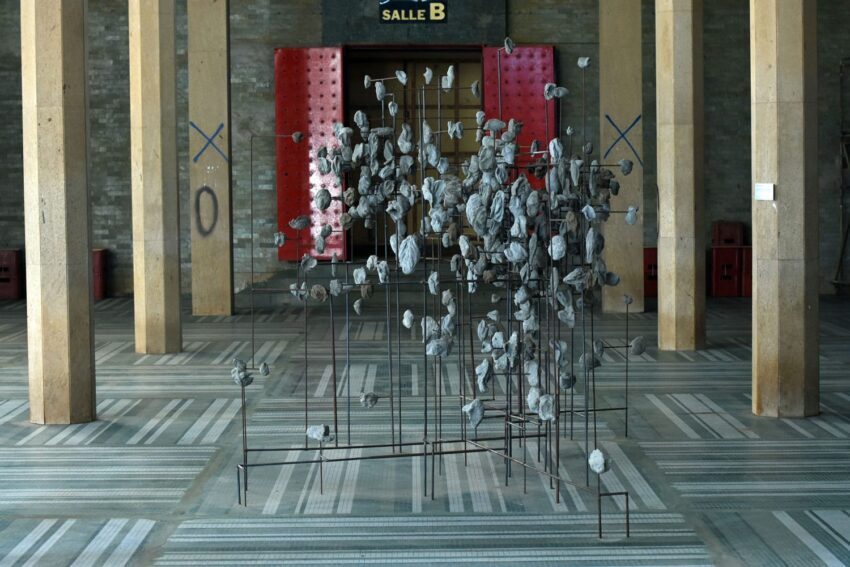

The works on show reveal themselves in an eclectic hodgepodge of styles, materials and subjects. Many have utilized materials that have become signature elements of the continent’s contemporary art: food packaging, African fabric, found metallic objects and so forth. This is seen in the packaging and cloth strips in Nigerian artist Olanrewaju Tejuoso‘s abstract wall piece to Haitian artist Pascale Monnin’s giant centerpiece installation made from parts of what appears to be window shades—their blue color clings to the sand on the ground where they were once before. There’s also Congolese artist Geraldine Tobe’s surrealist figurative depictions made with smoke on canvas, Ghanaian Godfried Donkor’s collage series “Olympians,” which reveals representations of the Senegalese national sport of traditional wrestling, and South African Ledelle Moe’s Exploded Geography, revealing pieces of concrete placed haphazardly on several long steel poles—it’s as if the earth had exploded and someone had to go and pick up the pieces.

“The hour of fulfillment opens the way to a new era where the individual rethinks his relationship with others and how to re-articulate his presence to the world,” continues Njama. Indeed, most of these works appear to ponder the idea of locality as well as identity—two major themes in the east-west migration dilemma. The works displayed in the various halls of the Palais de Justice beg such questions.

Nearby Marcos Lora Read’s ethereal Red House is an installation of fabric sails made by Egyptian artist Ibrahim Ahmed entitled Only Dreamers Leave. “The idea is to use sails as a metaphor for departure and migration and immigration,” says the artist who lives in Ardellewa, an informal neighborhood in north-west Cairo home to many Ethiopians, Eritreans, Sudanese and Somalis. Ahmed knew three Sudanese domestic workers who took a boat one night to flee in the hopes of a better life only to resurface two weeks later in an Italian prison. “It’s just one of many stories,” he tells Galerie. “This work is about people who dreamt of leaving but didn’t know the reality on the other side. I sourced textiles associated with domestic and labour work. They are porous and heavy and don’t function and the embroidery on some of these sails depict golden gates sourced from 19th and 20th century villas in Cairo referring to ideas of wealth and power—hence their gold color.”

However, says the artist, the golden gates have another meaning. “They reference the reason why people move for a better life. But the gates actually function to keep people out.” The artist’s flags represent the layering of dreams deferred and realized and the “dysfunctionality of these systems that are meant to segregate and keep people from moving.”

Not so far away is a work by Cuban, Havana-based artist Glenda León. Tiempo Perdido (Wasted Time II) is a giant mountain of sand topped by a small hourglass symbolizing the constant flow of time whose content has overflowed and formed the mountain that one sees as they visit the space. The work touches on León’s penchant for the fleetingness of time and life.

Both Rwanda and Tunisia are honored this edition with their own pavilions, a decision based on both countries’ creative growth and artistic depth. Of note at the Tunisian Pavilion is the lively work of abstract expressionist painter Thameur Mejri who presents a diptych painting titled Enemy 1 and Enemy 2. “The exhibition of Tunisia is curated under the theme ‘Hold the road’,” the artist explains. “We try to participate, despite all the counter-revolutions, as artists we try to hold the road, to carry out this democratic mutation and defend our freedom.”

Over 300 initiatives or satellite exhibitions are presented throughout Senegal for the duration of the biennale. A highlight for those visiting is a trip to the Île de Gorée just off the coast of the city. The scenic island was once a strategic trading post for the transatlantic slave trade. A variety of artworks are displayed here, notably an installation by renowned Senegalese artist Soly Cissé entitled Cotton Field situated in front of the church on the island. Now serene and peaceful, the former horrors of Gorée are inescapable and the works on show here grapple with how to interpret them in contemporary visual terms. This is the emancipation that The Red Hour signifies—the ability to balance the past with the present. This is the freedom that the artists in this edition so greatly strive for. And while there may be a clear lack of resources, various technological issues on the opening day, and some organizational preening to be done, the exhilaration of artistic discovery overcomes the biennale’s negative aspects. The Red Hour is a road to freedom.