Highlights From the São Paulo Art Fair

This year’s edition of SP-Arte featured a spectacular array of emerging and established Brazilian talents

Thirteen years ago, when art collector Fernanda Feitosa launched SP-Arte, the São Paulo International Art Festival, she never dreamed the Brazilian art scene could look as it does now. Back then, the fair, which takes place each April in the striking Oscar Niemeyer–designed Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion, was a more low-key affair.

“I started SP-Arte because I wanted to promote Brazilian artists locally and strengthen Brazil’s place in the global art market,” she told Galerie during the VIP opening. Before long, 27 international galleries were participating, a number that jumped to 58 in 2014. Feitosa credits the trust and strength of the local market for the return of international galleries, which hail from London to Berlin. (The fact that import duties are waived for international galleries and the state sales tax is lowered from 60 percent to 15 percent for the fair’s duration has helped as well.)

This year’s edition kicked off last week, with an influx of well-heeled Brazilian collectors meandering through the three-story space. And despite the strong contingent of major foreign galleries—including New York’s David Zwirner and Marian Goodman, Franco Noero from Turin, Kurimanzutto from Mexico City, and London’s White Cube—the fair was mostly a national affair, with 97 Brazilian galleries out of 132 total presenting spectacular works by emerging and established talents from across Latin America.

One fascinating aspect of the Brazilian art market is that, until recently, many artists—particularly modernist ones—have been appreciated in their home country exclusively. Feitosa believes this is changing: “Only now are they being discovered by international institutions and collectors and thrust onto the world stage,” she says. One of them is Alfredo Volpi, a mostly self-taught painter (1896–1988) who became one of Brazil’s most beloved 20th-century artists. Despite a considerable local following—almost every secondary-market dealer was offering his finely brushed paintings—Volpi had his first solo exhibition at New York’s Gladstone Gallery only last year, receiving much critical acclaim.

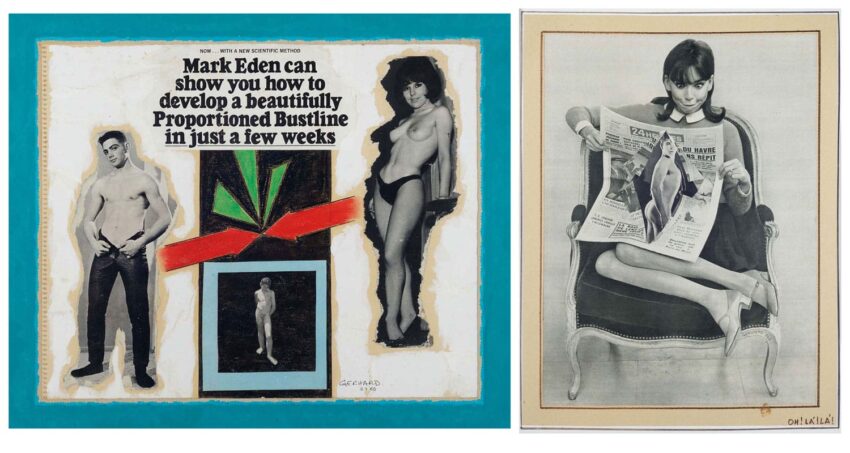

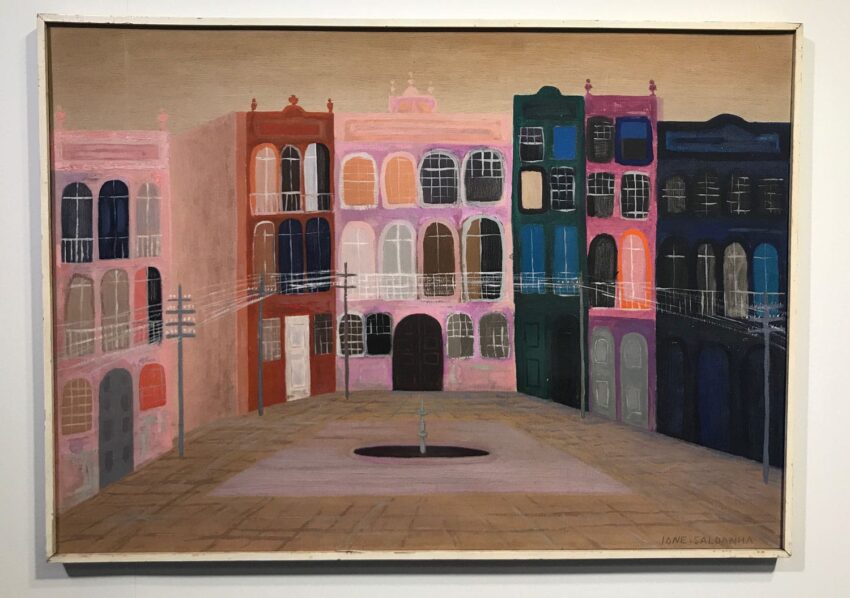

Other such artists were included in the fair’s intriguing “Repertório” (Repertoire) section, which featured 13 galleries selected by esteemed curator Jacopo Crivelli Visconti. Focusing on historic works by major international artists who are less known in Brazil, as well as significant yet overlooked Brazilian talents, this section showcased the late Ione Saldanha (1919–2001), who created delightful, Matisse-inspired depictions of colonial towns and clusters of hand-painted bamboo totems; mixed media works by Arnaldo de Melos using collected 1980s exhibition catalogues; and radical, Pop art–inspired magazine and advertising collages by Viktor Gerhard, among many others.

SP-Arte’s popular “Design” section also proved a success, as the genre is similarly gaining major international attention. “I found that the gallerists were bringing Brazilian furniture to decorate their booths, and collectors would often ask if they could buy it,” Feitosa noted with delight. Located on the building’s top floor, the section offered a wonderfully eclectic array of furnishings, ranging from rare colonial-era antiques and mid-century modern to contemporary design by innovative emerging talents.

Ana Neute, for example, generated buzz with a gorgeous lighting installation for Itens. Working with the “golden grass” native to Brazil’s Jalapão region, Nuente blends local craftsmanship with her elegant contemporary aesthetic. Spotlighting the influence of Brazilian modernism on contemporary design, Lissa Carmona Tozzi of São Paulo’s renowned Etel gallery curated an exhibition of historic Brazilian tea trolleys reinterpreted by contemporary designers such as Etel Carmona and Claudia Moreira Salles.

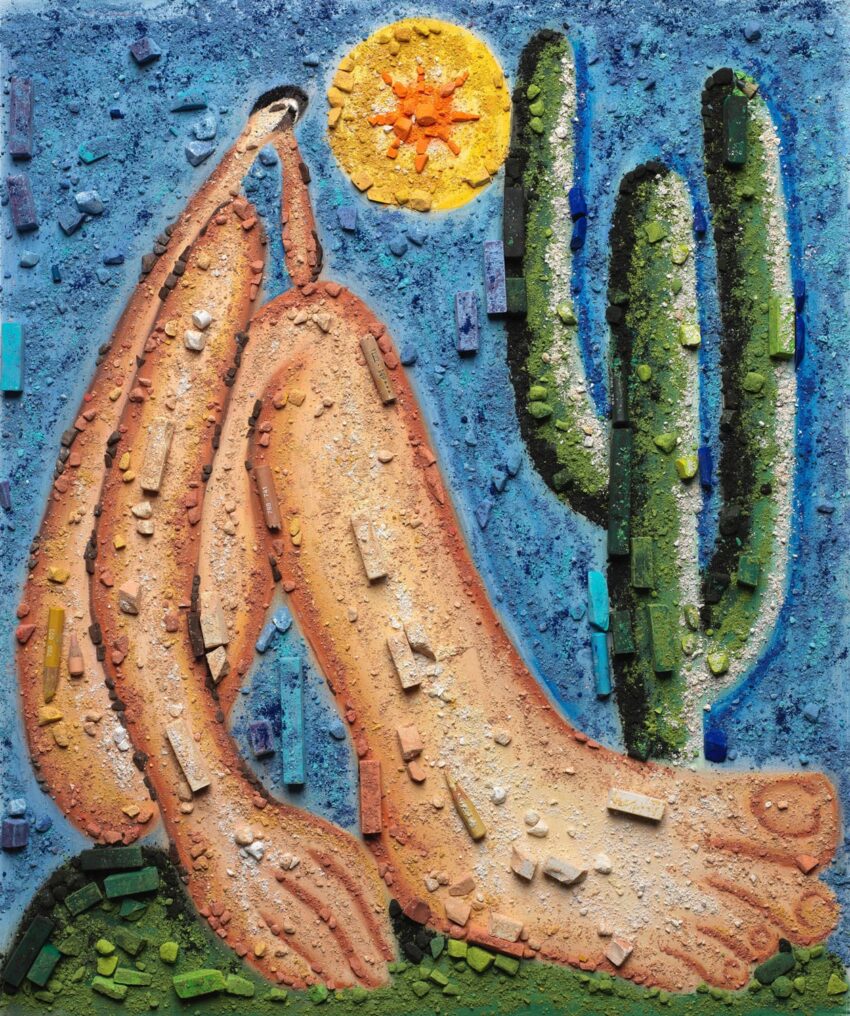

As in past years, the most prominently featured artists throughout the main floor were the recognizable names such as Vik Muniz, Tunga, Lygia Pape, Lygia Clarke, Nuno Ramos, Hélio Oiticica, Mira Schendel, and a large group of practitioners of Brazilian Constructivism, Concrete Art, and Abstraction. But exciting new discoveries by emerging talent were easy to make.

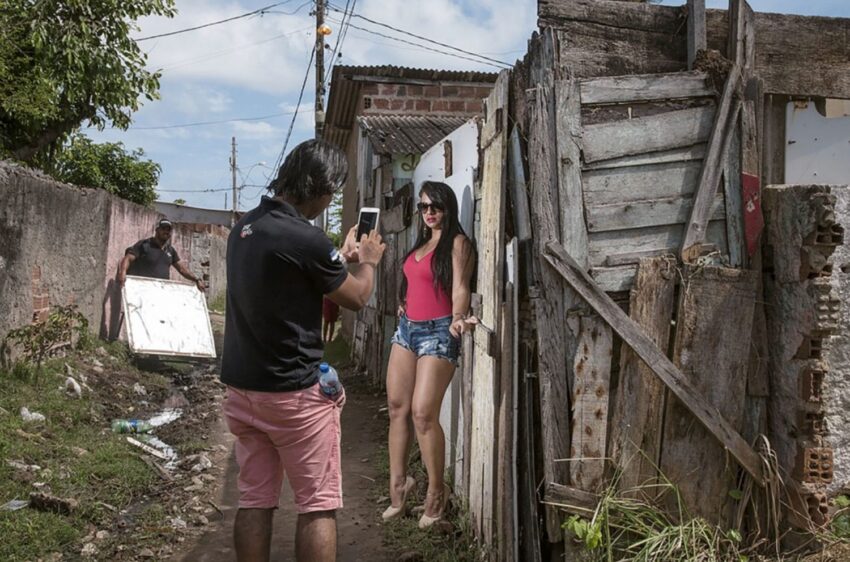

At Amparo 60, for example, a striking 2016 photographic series, “Masters of Ceremony,” by buzz-worthy talent Barbara Wagner caught the attention of collectors. Born in 1980 and based in Recife, in northern Brazil, the artist creates hyperreal, saturated photographs that give visibility of a middle-class society reaching out of the favelas of Brazil.

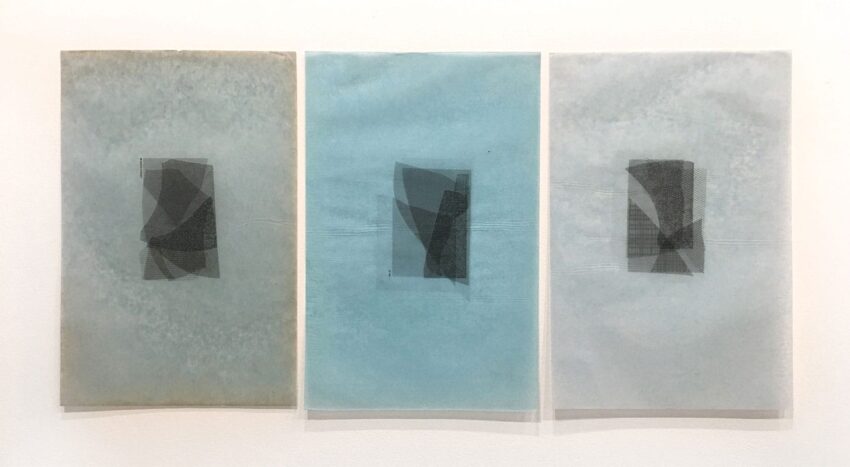

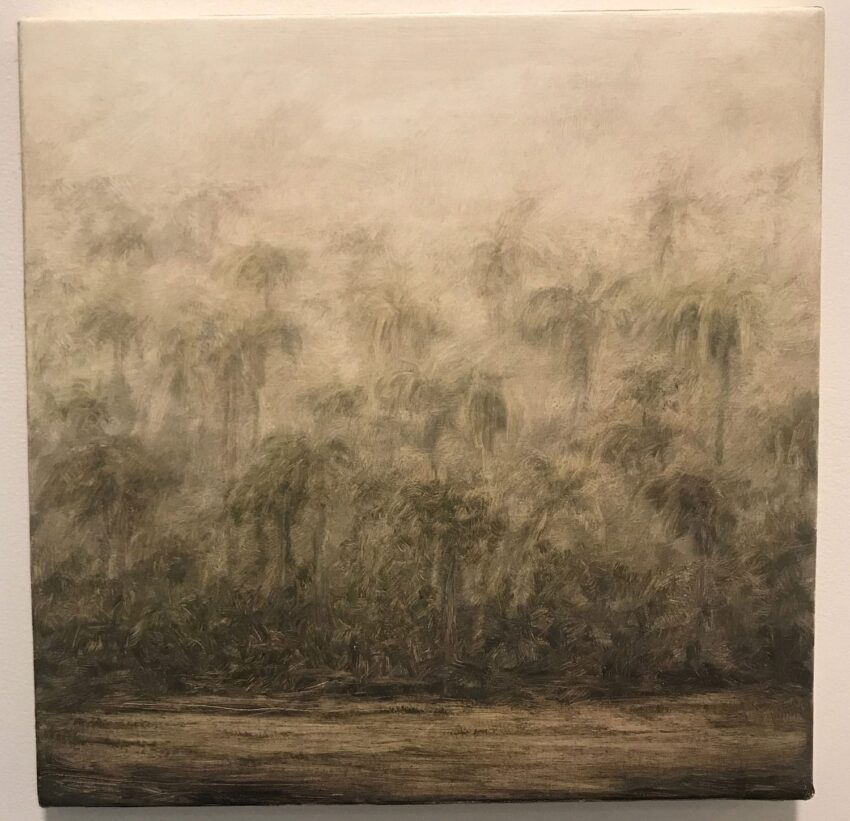

Lamb Arts and Galeria Raquel Arnaud both presented work by Future Generation Art Prize nominee Carla Chaim (b. 1983), whose quietly elegant, monochromatic works incorporate recordings of her body as she performs actions. Meanwhile, Casa Triangulo, a leading São Paulo contemporary gallery, offered a lush painting by Mariana Palma (b. 1979) that captured her country’s vibrant spirit thanks to a medley of intricate textiles, brightly patterned backgrounds, twisting exotic plants, and symbols of Baroque architecture. Another painter worth noting was Lucas Arruda (b. 1983) at Mendes Wood DM, a gallery devoted to promoting cross-pollination between international and Brazilian artists, with outposts in São Paulo, New York, and Brussels. Based locally, Arruda creates intimate landscapes that seem to radiate light and appear as though they were made in the 19th century.

Thread-based art was a huge trend. Some of the standouts were Vivian Caccuri’s (b. 1986) tapestries that incorporate broken stone or glass taken from construction sites around the country, at São Paulo’s Galeria Leme, to Marina Weffort’s (b.1978) almost invisible silk-thread panels delicately pinned on white canvas at Cavalo, from Rio de Janeiro. Among the very few works that addressed the Afro-Brazilian experience and the country’s history of slavery was an arrangement of terracotta vessels with oil paint and 22-karat gold leaf by Dalton Paula (b.1982), who is currently included in the New Museum’s triennial in New York.

While the country’s unstable economy and tense political situation (former president Lula da Silva was imprisoned for corruption-related crimes days before) were hot topics of discussion among dealers and collectors at the concurrent gallery openings and other art events, the mood inside the pavilion was hopeful–and confirmed why Brazil remains a creative powerhouse.