We Go Inside the Studio of Sean Scully Ahead of His Hirshhorn Show

The longtime master of abstraction is gearing up for major solo museum show

The first thing you should know about Sean Scully—the Irish-born U.S. painter and artist twice nominated for Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize—is that he’s sentimental. Painting’s last stalwart of modernist abstraction stands easily above six feet, in the sort of frame that served him well as a teenage street fighter, but what lies inside him is rather tender.

He freely admits as much. “Basically, I’m incredibly emotional,” Scully blurts out unabashedly, in his Irish-inflected Cockney cadence. (Born in Dublin in 1945, he was raised in South London, settling in New York after a graduate fellowship at Harvard in the early ’70s.) After all, evidence of this trait is on the wall.

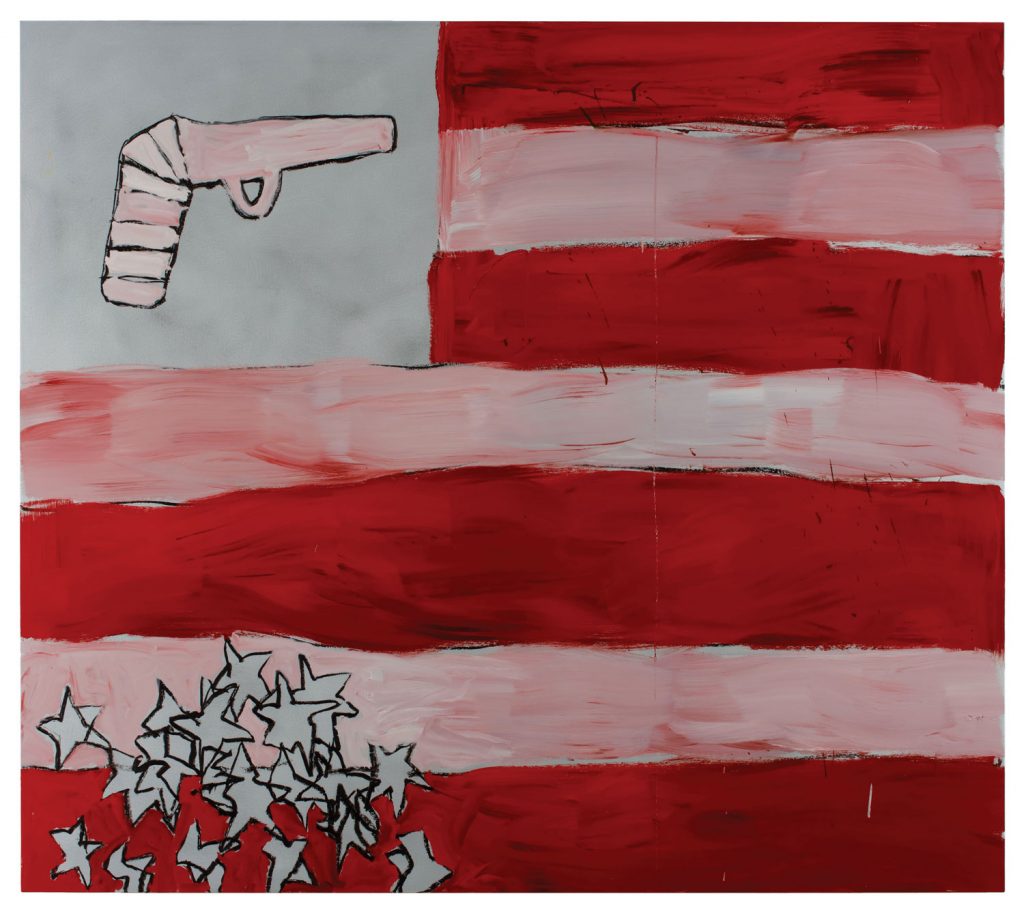

The works hanging in Scully’s towering Hudson River studio these days are moody oils on aluminum from his “Landline” series; vibrant figuratives of his son, Oisín, his “greatest creation”; and his latest addition, a six-painting manifesto featuring American flags with fallen stars, the result of his need to reflect on the American obsession with guns. “And thus ends my career as a political artist,” he says.

Recommended: Sean Scully’s Abstract Masterpieces Take Over a Mexico City Landmark

Expression as an intellectual pursuit and a physical state is what leads Scully to the studio nearly every day of his life. “I love working. I admire it in people, too,” he says, and his unflinching practice has kept him in favor among dealers, collectors, and curators alike since the ’60s. But that’s not the only secret to his success. “You can’t rely on me to be a good boy,” he chuckles. Indeed, Scully’s rebelliousness—from his emotional landscapes to his going against the tide as an abstractionist in a sea of figuration—has sustained his five-decade career. “You know, I was a star out of art school. I’m not crippled by modesty,” the painter says. “But really, you’ve got to be unstoppable, and to be unstoppable you’ve got to be connected to life force, or energy.”

Scully’s energy is on display this year and into the next with some 20 solo exhibitions across the globe, from the Forte Belvedere and the Museo Uffizi in Florence, Italy, in June to the De Pont Museum of contemporary art in Tilburg, the Netherlands (through late August), and the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in Wakefield, England (September 29–January 6, 2019). Concurrently, Scully will have a homecoming of sorts at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., where his “Landline” series will be on view from September 13, 2018 through February 3, 2019. (His last show there, in 1995, was a sweeping mid-career retrospective.)

Drawn from natural surroundings and rendered in colors both subdued and bright, the contemplative series has occupied the painter for the better part of this decade. Each work’s hues are, to some degree, a reflection of Scully’s whereabouts: He has moved his main studio from Manhattan to a Hudson River town, and has been spending more time in London, where he has a residence. Scully also maintains studios in Berlin and rural southern Germany.

The infinite lines of his atemporal horizons will meet their match in the Hirshhorn’s iconic curving walls, in an infinite loop that “will just run around and around and around forever,” Scully says. Impervious to time and evocative of the divine, his “Landline” works, like his paintings overall, knock at the ineffable, that indescribable something else about being human. As he would say, “I really do believe we’re angels in the making.”

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2018 Summer Issue under the headline Artistic Rebel. Subscribe to the magazine.