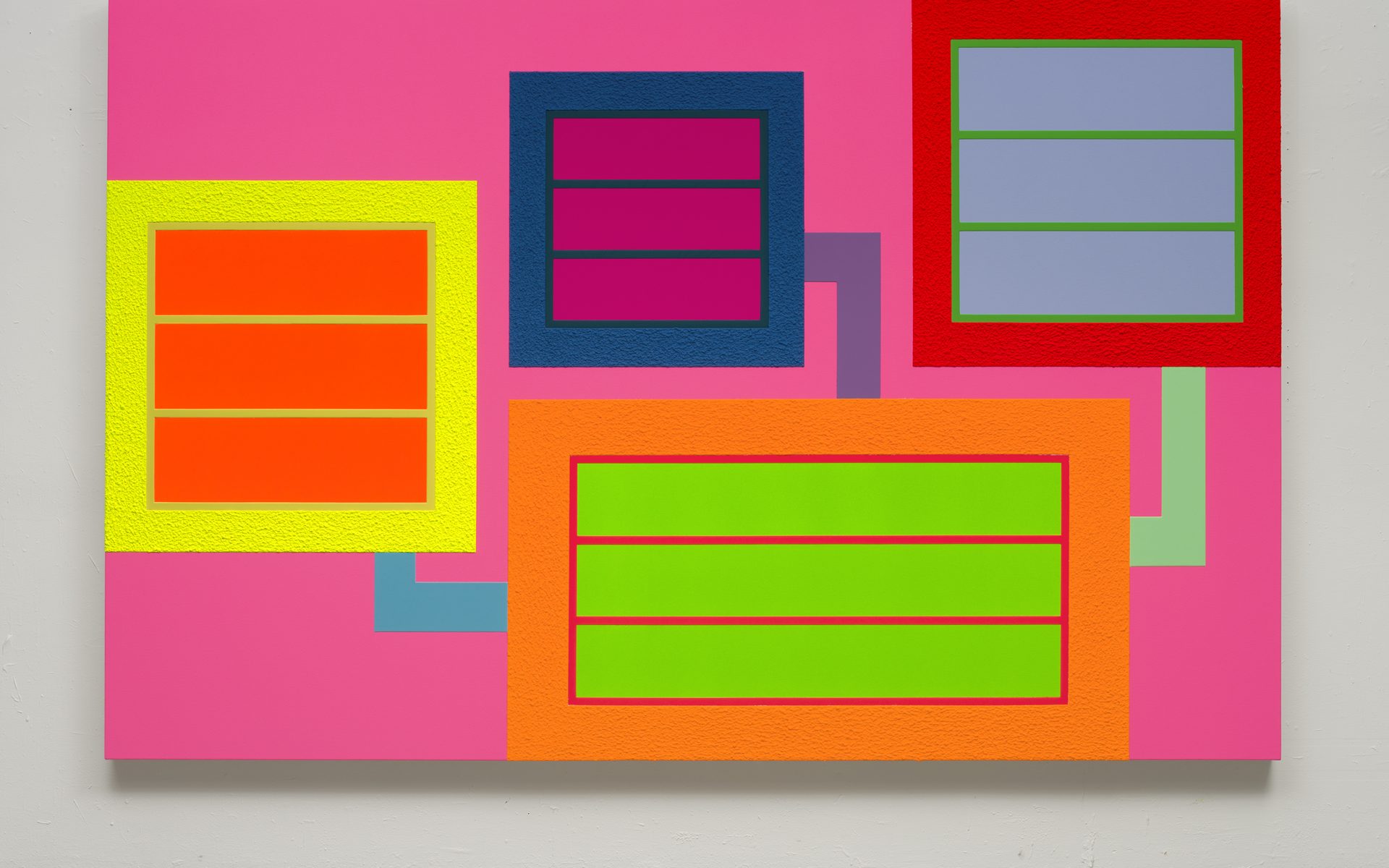

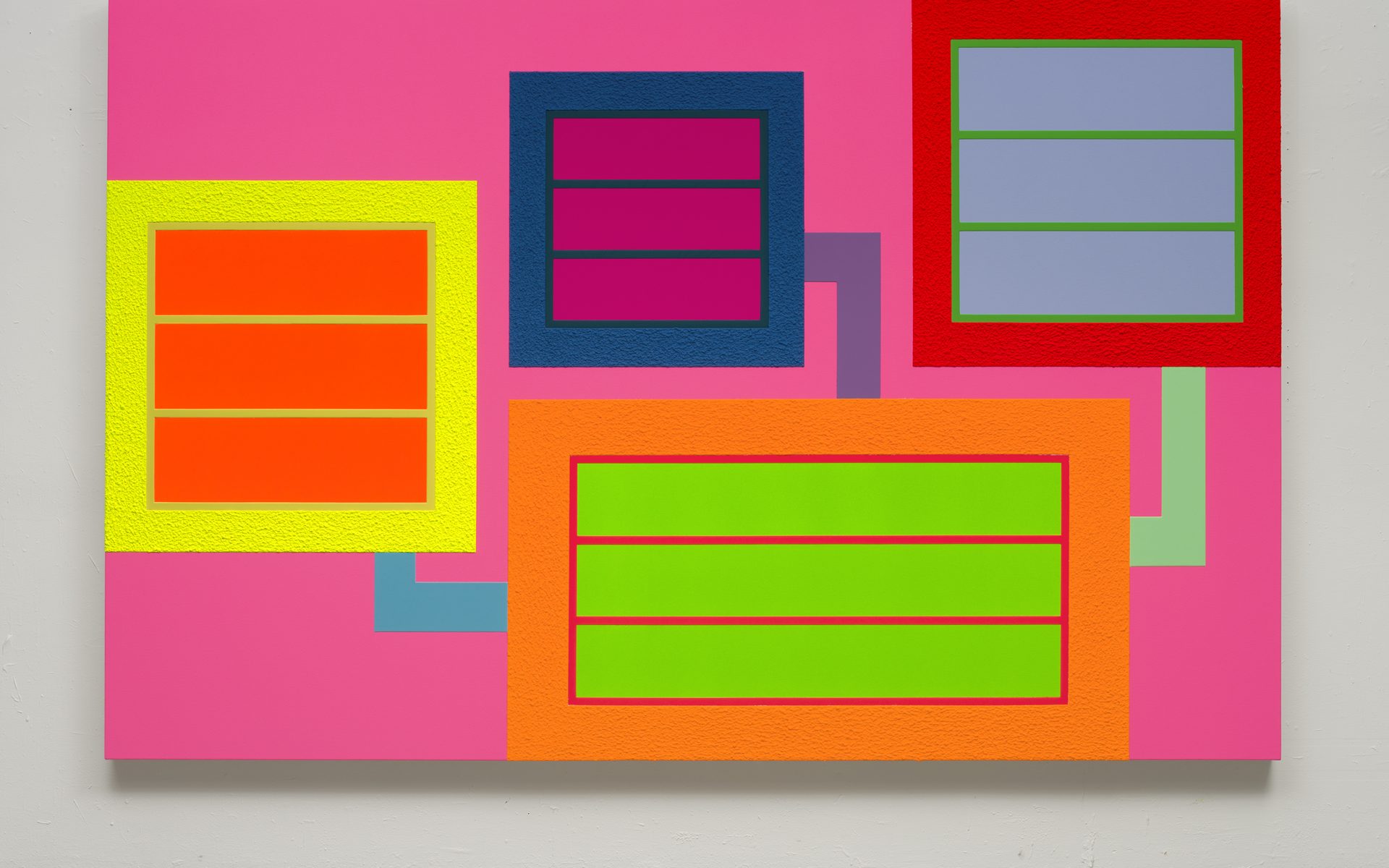

Peter Halley, Here and Now, 2018. Fluorescent acrylic and Roll-A-Tex on canvas 70 x 108 inches.

Peter Halley, Here and Now, 2018. Fluorescent acrylic and Roll-A-Tex on canvas 70 x 108 inches.

Beginning Thursday, if you walk by Lever House in midtown Manhattan at any time of day or night, you will notice that the glass-walled mezzanine floor, which is visible from the street, is bathed in an acidic yellow light. The otherworldly glow isn’t fallout from some nuclear event but a new exhibition by artist Peter Halley—his largest to date—and the experience, according to curator Roya Sachs, is meant to feel like stepping into one of his Day-Glo paintings.

Seeing the radiant gallery from across the street is simply the first “level of interaction” with Halley’s work—there are four in total, including an encounter with a mazelike structure that you’ll be able to walk through. Halley, who rose to fame in the East Village art scene of the 1980s, became known for his fluorescent paintings inspired by the geometric urban landscape around him. “If you look at the plan of the installation from above,” says Sachs, “it looks like a circuit from a one of Peter’s paintings.”

Roya Sachs, curator of the Lever House Art Collection. Photo: Courtesy of Lever House Art Collection

The show is the fourth at this space for Sachs, who has been the curator of the Lever House Art Collection since 2017. In the past year, she has staged ambitious exhibitions with Reginald Sylvester II, Adam Pendleton, and Katherine Bernhardt, the last of which saw Bernhardt extending her work beyond the canvas with colorful dyed, soft “gummy worm” sculptures and an indoor garden incorporating plants, painted cement blocks, and bottles of Windex.

Likewise with Halley, Sachs encouraged the artist to explore new mediums, an effort that resulted in the six new cut-canvas works featured in the installation.

We had a chance to discuss the new show with Sachs and how she’s attempting to introduce Halley’s work to a whole new generation of art connoisseurs.

Galerie: Tell us about this exhibition. How did it come about?

Roya Sachs: When we’re deciding who to invite to do a commission, Aby Rosen and Alberto Mugrabi have always been long time fans of Peter’s work and we’d discussed the idea of working with [Halley] for a while. I think that because Lever House has such a strong architectural identity, it’s always really important to us to find an artist who we think will be able to engage and create a dialogue with the space, but also be able to come and disrupt that and bring their own identity to it. I think this is an exciting moment where Peter has really allowed himself to step out of his confines and do something completely new.

Can you tell us more about the installation and what inspired it?

Peter’s always loved Lever House. He grew up a few blocks away, and it was built the year before he was born. He had this childhood connection to the space. With the interesting infrastructure and the skeleton of the building, we had so many talks about what the experience of walking into a Peter Halley painting would be like. If you look at the plan of the installation, from above it looks like a circuit from one of Peter’s paintings. From there, Peter designed this sequential narrative of how the installation works.

There are four different levels of interaction. The first is when you’re a few blocks away and you’re going to be able to look up and see the entire second floor, which will have an acidic yellow glow coming out of it. Then the experience of approaching the Lever House and seeing it from outside. And then as soon as you walk in to the exhibit, there’s a structure in the center of the space, where there are going to be six new paintings, and these are new cut canvases, which is an entirely new medium for Peter. And then within that structure you’re able to walk through a mazelike corridor in which you’ll enter two separate rooms, which will include a series of digitally rendered mural works.

How would you describe Peter’s work and his style to people who are unfamiliar with it?

Peter’s work is so important, especially in the context of New York in the 1980s. He was a key figure in the neo-Conceptualism movement, and his career has spanned over 40 years. So he’s someone who is very much reacting to the environment in which he’s in. Which makes sense in New York because you have this very rigid, geometric urban plan, and I think that’s something you can see within his geometric compositions of his paintings. They’re these prison cells and conduits that are in conversation with one another that are addressing both the social but also the structural environment of contemporary society.

Was the experience of curating this show different from other exhibitions you’ve worked on?

Every commission is very different and very unique because each artist works in a different way. Some artists are focused on the dialogue and trying to figure out what a project should be. In other instances, artists immediately have a clear vision of what they’d like to do and they follow through on that. I try to play the role of being on the sidelines and only being there when I’m needed and when dialogue is needed. I’m there to give context, the context and the history of the building and to try and contextualize that within the realm and the work of the artist. Sometimes that’s more necessary than other times, but it’s always a conversation. I try to help artists feel confident in trying what they’d like to do and hopefully to make their vision come to life.

Recommended: Richard Tuttle Talks to Galerie About His Phillips Collection Show

How is the space challenging?

The space is challenging in numerous ways. It’s essentially this glass box and it’s not outdoors but it’s not indoors. It’s not public but it’s not private. It’s all of the above and you’re having to think in context of several different structures. Coming into a space that isn’t this white-walled gallery in which your work can really stand on its own, artists are having to come in and either disrupt or engage with the architecture and all of the materials that you’re dealing with—from marble to aluminum pillars to windows—and see the way in which your work can carry a presence. So, in that sense, you’re having to find new and different ways to present the work that will be both engaging from the outside and from the inside.

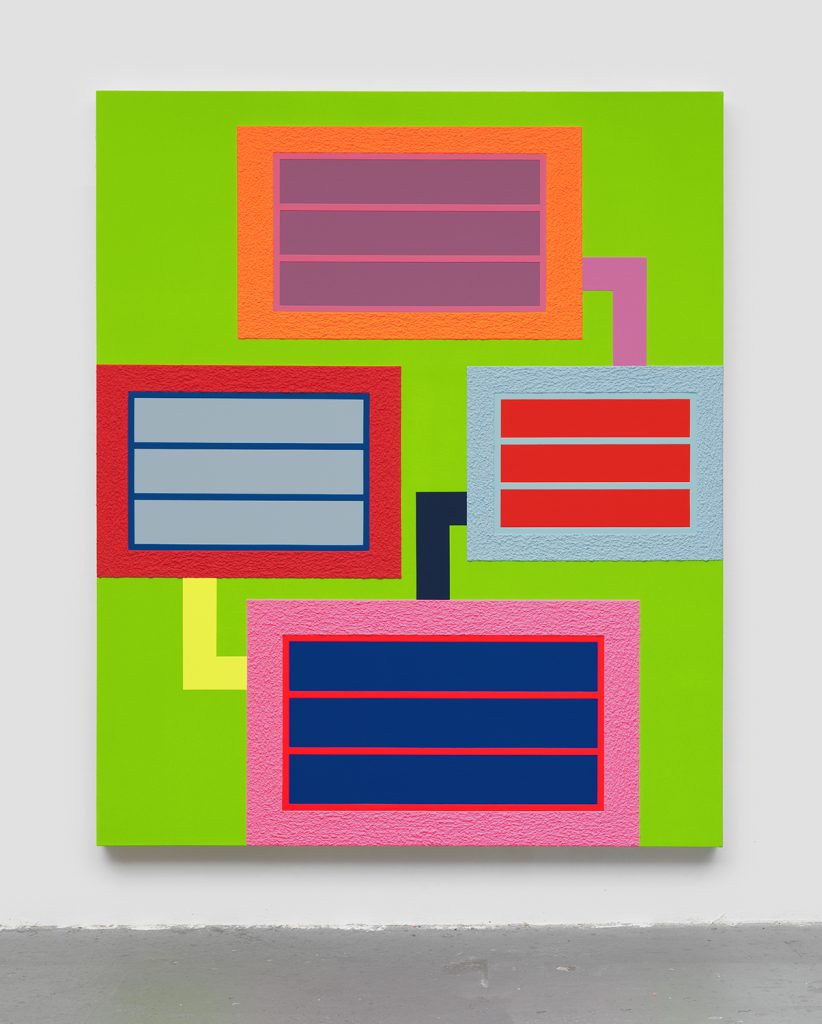

Revolt by Peter Halley, seen in his 2017 exhibition at Greene Naftali. Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

What do you hope visitors take away from this show?

I think that one of the most important things in general about art is having a reaction to something. I feel that we are losing a sense of how we’re supposed to react, and we see so much work that we forget to react oftentimes. We forget to engage and to allow ourselves to step out of our comfort zones and think about an artwork differently. This is a really beautiful moment where Peter is able to present an entirely new conversation and to present it to an entirely new generation. So what I really hope is that audiences come together from all generations and are able to take in Peter’s work in a new way and understand its past but also where it’s going.

Cover: Peter Halley, Here and Now, 2018. Fluorescent acrylic and Roll-A-Tex on canvas 70 x 108 inches.