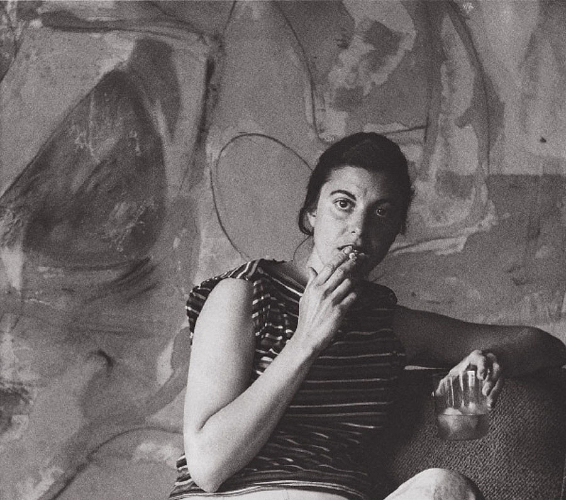

Helen Frankenthaler in the Spotlight This Summer

With a slew of summer exhibitions from Paris to Texas, the late Abstract Expressionist painter is finally receiving the solo attention she deserves

Much of artist Helen Frankenthaler’s work is especially suited for summer viewing. Vibrant and spontaneous, her prints and canvases offer a warmth and energy that remind us of nature. And a handful of international galleries and museums seem to agree. Institutions from Paris to Texas will be exhibiting work by the late American Abstract Expressionist, revealing a renewed interest in her work from a variety of perspectives.

Though art history has traditionally grouped Frankenthaler in with—or rather omitted her from—the group of midcentury Abstract Expressionists including Jackson Pollock, Willem deKooning, and Robert Motherwell (her husband for a time), she’s now receiving the solo attention she deserves.

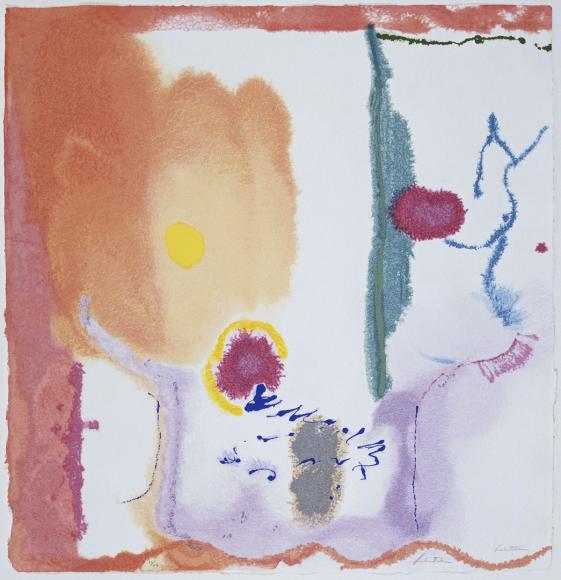

From June 9 through September 16, Gagosian in Paris is showcasing “Helen Frankenthaler: After Abstract Expressionism, 1959-1962.” The city’s first major exhibition of Frankenthaler’s work in more than five decades, the exhibition explores her return to gestural improvisation after years spent developing her “soak-stain” technique (soaking her raw canvas with turpentine-thinned paint). Fourteen paintings and two works on paper spotlight just three years of the artist’s six-decade long career.

The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, MA, is devoting two shows to the artist. One is focused on her relationship with the landscape, “As in Nature: Helen Frankenthaler Paintings,” curated by Alexandra Schwartz, and one on her innovative approach to woodcut prints, “No Rules: Helen Frankenthaler Woodcuts,” curated by Jay Clarke.

According to Schwartz, a few different factors have led to Frankenthaler’s reevaluation. Abstract Expressionism, she explains, “is being looked at anew from a lot of different perspectives… really going beyond the traditional canon.” And art historians are increasingly revisiting the women of the moment. Additionally, there are several younger female artists like Natalie Frank (b.1980) and Dannielle Tegeder (b.1971) looking to Frankenthaler’s body of work for inspiration. (Both are giving talks at the museum.)

Interest in Frankenthaler has waxed and waned. “Twenty years ago, she was one of the most successful contemporary women artists out there. She then went through a period of not having as much attention. It’s been interesting to look at her work anew and think about why there is a dormant period,” Clark says.

Down south, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, TX, is exhibiting Frankenthaler prints more expansive in their techniques: lithographs, etchings, aquatints, screen prints, and woodcuts. “Fluid Expressions: The Prints of Helen Frankenthaler” is on view through September 10. As curator Michaela R. Haffner explains in the show’s publication, Frankenthaler was at first reluctant to make prints; the process was antithetical to the instinctive and personal nature of Abstract Expressionist painting. Ultimately, though, the flatness of lithography attracted her.

Frankenthaler’s reputation as a painter rather than printmaker is consistent with other Abstract Expressionist artists who also worked in printmaking: Pollock, De Kooning, Johns, Mitchell. “It is an age-old historical bias,” explains Clark. “The discourse is about them as painters and to a far lesser extent printmakers.”

Showing how she fits into different art historical narratives, her work is also part of group shows at the Montclair Art Museum in Montclair, NJ, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. An exhibition at the former, “Matisse and American Art,” (through June 18) explores Matisse’s influence on American modern art from 1907 to the present, while one at the latter “Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction,” (through August 13) displays female abstract artists’ accomplishments between 1945 and 1968.

Recently, critics have called on institutions to include more female artists in their exhibitions and permanent galleries, altering the male-dominated narratives of American art. And while progress in that direction may be slow, this summer’s focus on the often-overlooked Frankenthaler seems like a good sign.