Inside Keith Sonnier’s First Major U.S. Exhibition in 35 Years

With three shows on Long Island this summer, the artist is making a splash

One of the most unexpected and engaging works one will encounter at the Keith Sonnier exhibition on view at the Parrish Museum in Water Mill, New York, is Quad Scan, a set of speakers and CB scanner broadcasting a live feed from ship-to-shore and ham radio. The work was created in 1975 and acquired by Andy Warhol in a barter with Sonnier—the two artists were friendly, having been in a few exhibitions together.

“Andy wanted it to be installed in the reception room at the Factory,” said Sonnier in a recent interview. “It was hilarious and it worked out just how he wanted it to. It was a big hit and great for Andy to live with the work in a different way.”

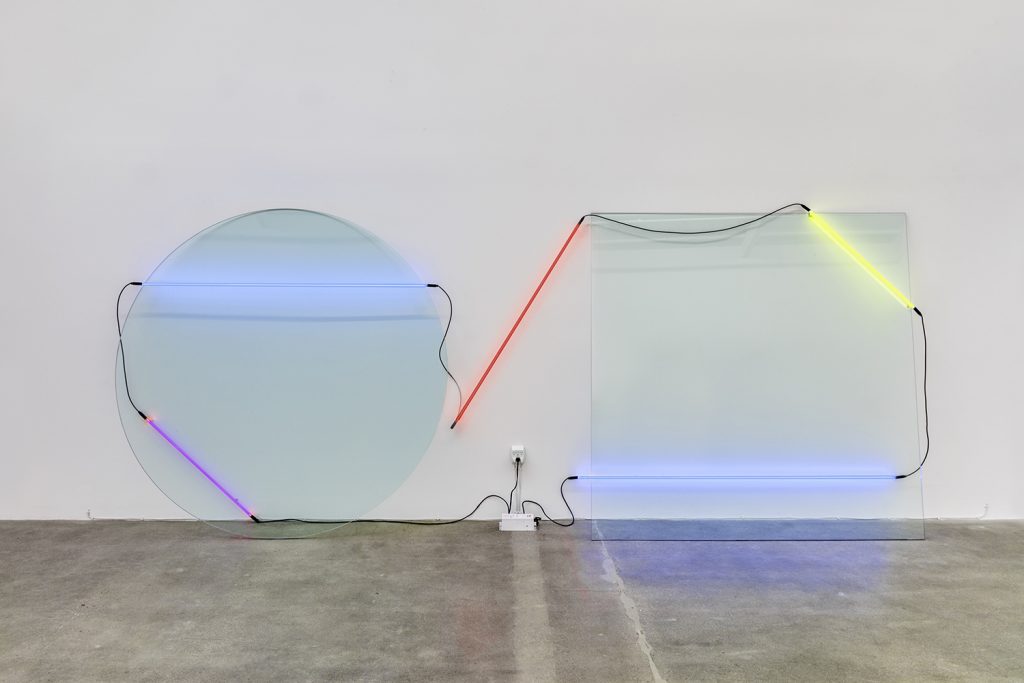

The exhibition at the Parrish spearheads a trifecta of summer shows on the East End of Long Island that explore the variety and breadth of his practice with neon and beyond, including one at Dia Art Foundation’s Dan Flavin Art Institute, which will be on view through May 2019, and a show at Tripoli Gallery in Southampton, which was on view through July.

Recommended: A Look Inside the Whitney Museum’s First Fashion Exhibition in 20 Years

Quad Scan, unlike his neon works, offers an audio-sculptural component that complements the neons he is most recognized for and allows the viewer to have a more engaging experience. This intention of projecting sound is also mirrored to some extent in the 1981 sculpture Trois pattes (TRIPED), which is made of bamboo and aluminum with a functioning radio attached to one of the “legs” of the work. Sonnier equates the title to a French saying, “Ça ne casse pas trois pattes à un canard,” an idiom that basically translates to “Nothing to write home about,” or “No big deal.”

amplified radio, loudspeaker, and electrical wire, 108 x 42 x 54 inches. Photo: Collection of Barbara Bertozzi Castelli, New York. Image courtesy Keith Sonnier Studio.

The radio broadcasts music in real time and, like the feed from Quad Scan, transmits contemporary audio into the gallery filled with otherwise dated work, thereby updating the entire exhibition. What someone might have heard in 1981 is different from the contemporary pop songs being played on the day of my visit. Through this audio communication, the sculptures are given renewed life and will always in a sense remain in the present.

“One of the beauties of working with an artist like Keith is that he has a lot to say to every generation of artist that comes along,” said Terrie Sultan, director of the Parrish Museum, who cocurated the show with Jeffrey Grove.

The show at the Parrish (which remains on view through January 2019) is Sonnier’s first major show in the United States since 1983. Well-suited for the vaulted ceilings of the Parrish, one of the first works that visitors will come across is Passage Azur, 2015/18 installed along the main hallway of the venue. The cool-toned neon tubes twist, bend, and stretch the length of the corridor, a calligraphy of sorts. The work was installed by Sonnier himself in a site-specific configuration specifically for the Parrish and is flanked below by Quad Scan, hints of color from the neon inviting viewers to gaze upward.

The exhibition at the Dan Flavin Art Institute explores Sonnier’s interest in light, film, and experimental environments. On the lower level is Dis-Play II, a mixed-media, sculptural installation composed of neon, black light, strobe light, plywood, and glass that Sonnier made in 1970, during the height of Flavin’s own time experimenting with neon. While the original artwork was made using a toxic pigment, this new iteration utilizes a nontoxic version, although it’s still not meant to be touched. These works are accompanied by Film and Videos 1968–1977, a montage of short films shown in a loop that serve as studies in sound and media.

“Though Sonnier’s installation Dis-Play II was conceived more than 40 years ago,” said Courtney J. Martin, chief curator of Dia’s Dan Flavin Art Institute, “it resonates with more recent artmaking [practices] because it relies on the activation of elemental senses, such as sound and sight.”

Of all Sonnier’s sculptures and media choices, his use of audio seems to be the most timeless, while his neons feel more connected to time. A bulb can burn for only so long before it goes out.

“I love the idea of trapped gas,” said Sonnier, referring to his initial attraction to neon. “There is a certain type of imagery associated with it, such as the remembrance of old cities that used to be lit with gaslighting. Before that, there were only candles.”

His nostalgic musings transform the way that most of us might think about neon lighting. The general consensus may be to contemplate store signage, the blinking alert vacancy or no-vacancy at a roadside motel, Times Square, or even the contemporary neon shapes available at every Urban Outfitters, meant to decorate the bedrooms of teens and millennials. Yet Sonnier thinks of trapped gas. Perhaps there is nothing more contemporary than to be connected to the history and technicality of what allows light to glow.

From the 1960s through today, Keith Sonnier has made work that challenges others on how to think about light and space. Unlike his peers, such as Richard Serra or Robert Morris, he has always been candid about giving the viewer hints as to what he’s about. These three exhibitions provide an opportunity to look and make up your own mind between the differences of yesterday and today.

“Just in terms of his composition and color, the narrative aspect of it and his concepts of thinking about objects in relationship to space and architecture,” said Sultan, “especially for up-and-coming sculptors, these types of questions are just as relevant right now as they ever were.”