The centerpiece of Glenstone’s vastly expanded campus is the Pavilions, a 204,000-square-foot gallery designed by Thomas Phifer.

The centerpiece of Glenstone’s vastly expanded campus is the Pavilions, a 204,000-square-foot gallery designed by Thomas Phifer.

The centerpiece of Glenstone’s vastly expanded campus is the Pavilions, a 204,000-square-foot gallery designed by Thomas Phifer. Photo: Iwan Baan, Courtesy of Glenstone Museum

A monumental pony head, modeled on a child’s toy rocker, rises on a bucolic slope near the entrance to Glenstone, a museum of modern and contemporary art on 230 acres in Potomac, Maryland. Towering 37 feet high and planted with a tapestry of colorful flowers, the surreal and playful sculpture by Jeff Koons, titled Split-Rocker, perfectly embodies the spirit of this sanctuary created by Mitchell and Emily Rales.

“We wanted to build something that was about the seamless integration of art, architecture, and landscape,” says Mitchell. His good fortune in business, including his cofounding of the Danaher Corporation, a life-sciences and diagnostics company, has helped the couple establish and support the Glenstone Foundation, which has a collection of some 1,300 pieces by more than 200 artists, with particular depth in works by Roni Horn, Ellsworth Kelly, and Louise Bourgeois, among others. Now, with the strong architectural interpretation of Thomas Phifer, the museum that the Raleses envisioned has come to fruition.

Emily and Mitchell Rales. Photo: Courtesy of Glenstone Museum

In 2006, the couple first opened the art collection to the public, for free and by appointment, in a museum designed by the late Charles Gwathmey, who also built their home on the property. Starting October 4, visitors will be welcomed to a campus vastly expanded by Phifer. The centerpiece is a new, 204,000-square-foot gallery building called the Pavilions, which, from a distance, resembles a village of 11 discrete structures but actually forms an interconnected whole. Phifer has also designed new amenities, including an arrival hall and one of two freestanding cafés. Glenstone will now be able to handle 100,000 visitors annually, up from 25,000 in years past.

Recommended: Inside Scotland’s Stunning New V&A Museum in Dundee

The sections of the Pavilions are rectilinear volumes with their own proportions, rising as high as 60 feet and built from six-foot-long concrete blocks. “They stack up kind of Egyptian style,” says Phifer. He has organized this “house of rooms,” as he calls it, around a central water garden with lilies and irises encircled by a glass-walled passageway that connects the pavilions. “You have this calming experience with the landscape as you move from room to room,” Phifer says.

The water court of the Pavilions. Photo: Iwan Baan, Courtesy of Glenstone Museum

A number of rooms, each filtering natural light through oculi or clerestory windows, are dedicated to installations of single artists, including Cy Twombly, Charles Ray, Lygia Pape, and Brice Marden. Sometimes the design of the room came first, and then Emily, as curator, determined the right works for the setting. “We wanted one really tall room with abundant light that floats down,” says Emily, who selected for this towering space three large paintings by On Kawara that commemorate the significant dates of the first moon landing.

Jeff Koons’s Split-Rocker. Photo: Iwan Baan, Courtesy of Glenstone Museum

In the gallery for Michael Heizer, the only pavilion without a ceiling, the open-air room was built in response to an immense sculpture called Collapse. Fifteen beams of weathered steel, some as long as 42 feet, appear to have crashed into the earth and landed in a jumble inside a 16-foot-deep, metal-lined crater. “It’s about chaos and what happens if you were to possibly drop these from a very tall height,” says Emily. Conceived in the late 1960s, the piece has never before been executed at this scale. Another monumental earthwork by Heizer has been completed outside the Pavilions, joining sculptures sited in the fields and forest at Glenstone by Richard Serra, Tony Smith, Andy Goldsworthy, and Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller.

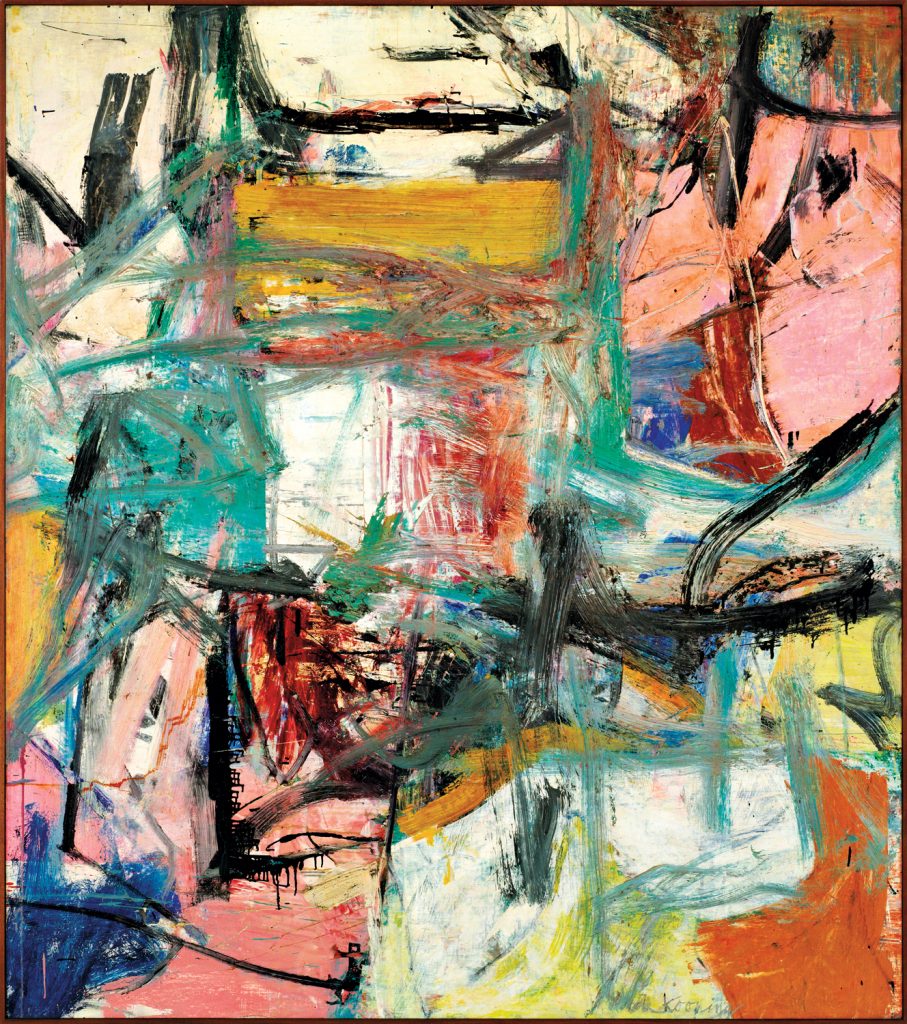

Willem de Kooning’s January 1st (1956), featured in the Pavilions’ first exhibition. Photo: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4art, Courtesy of the Glenstone Museum of Art

In the largest of the pavilions, Emily has organized a show of what she calls the “greatest hits” from Glenstone’s collection. The first galleries begin where the couple started collecting: with Abstract Expressionist canvases by Franz Kline, Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning. These are juxtaposed with more recently acquired looped-wire hanging sculptures by Ruth Asawa. “It’s important that in the retelling of this period of time, we include works by women,” says Emily, who is also intermixing in this exhibition concentrations of Japanese and Brazilian artists with a more established Western canon of works dating up to 1989.

“There’s an emphasis on radical form and pushing boundaries,” says Emily. “The whole premise of the collection is based on challenging the notion of what constitutes a work of art.”

Sculptures by Ellsworth Kelly and Richard Serra are seen near The Gallery. Photo: Scott Frances, Courtesy of Glenstone Museum

The passage in the Pavilions. Photo: Iwan Baan, Courtesy of Glenstone Museum

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2018 Fall Issue under the headline Field of Dreams. Subscribe to the magazine.

Cover: The centerpiece of Glenstone’s vastly expanded campus is the Pavilions, a 204,000-square-foot gallery designed by Thomas Phifer.