Take an Art History Tour of Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s New Music Video

The duo take over the Louvre Museum to visit the Mona Lisa and the Venus de Milo

Leave it to Beyoncé and Jay-Z to take over the Musée du Louvre for their latest music video in a grand fashion. Titled “Apes**t,” their latest collaboration features the power couple, along with dancers, using the famous Paris museum as the backdrop and putting their own artistry in juxtaposition with the trove of Western artworks in the collection.

The Carters are no strangers to the art world. In just the last couple of years, Beyoncé worked New York-based artist Awol Erizku for her internet-breaking pregnancy photo shoot, Jay-Z created a performance video, titled “Picasso Baby,” using famous art figures and celebrities at Pace Gallery, and even their 6-year-old daughter made headlines for bidding on a $19,000 Sidney Poitier painting at a Los Angeles benefit.

This video, however, ups the ante—not only in terms of complexity but also sophistication. The works featured are not only some of the most famous in the museum, but the most important in the art historical canon.

Here, we share the fascinating art history behind the works.

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo, known as the Mona Lisa (the Jocondein French) c. 1503–19

The world’s most iconic artwork—and without doubt the one that draws the biggest crowds at the Louvre—is the Mona Lisa. It is here we first see Beyoncé and Jay-Z, posing in pink and sea-foam green suits, respectively. Painted by Leonardo da Vinci circa 1503-1519. Though the portrait is thought to be of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine cloth merchant, the circumstances under which the painting was made and the identity of the sitter are still shrouded in mystery.

Jacques-Louis David, The Coronation of the Emperor Napoleon I and the Crowning of the Empress Joséphine in Notre-Dame Cathedral on December 2, 1804, 1806-07

Jacques-Louis David’s monumental work combines astounding historical accuracy and artistic mastery. David actually attended the coronation and used real ceremony participants as models while also crafting miniature reconstructions of the ceremony in his studio. His use of light brings the viewer into the center of the scene where Napoleon crowns Empress Josephine—a symbolic gesture of the unity between husband and wife as well as well as between France under Napoleon.

The Winged Victory of Samothrace, c. 190 BC

Discovered on the Greek island of Samothrace, this commanding Hellenistic sculpture depicts the Goddess of Victory (Nike in Greek) as though she is about to take flight. The sense of movement is conveyed through the outstretched wings and carved billowing folds of fabric. Perched at the top of the Daru staircase, it is one of only a handful of original Hellenistic works left in the world.

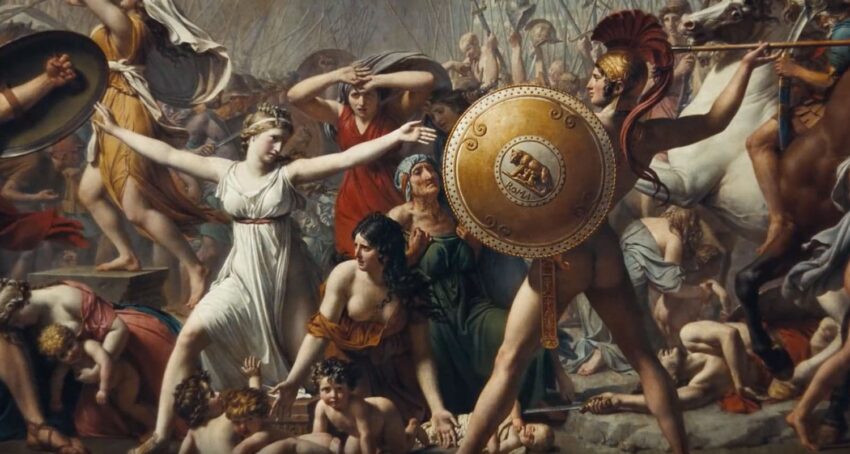

Jacques-Louis David, The Intervention of the Sabine Women, 1799

This Jacques-Louis David work depicts the abduction of the Sabine women by the Romans—a scene that has been depicted countless times throughout art history. This version of the story has the women attempting to subdue the violent battle scene. Created by David at the end of the French Revolution—a period of bloodshed and vast changing political governance—he wanted to show that through violence and turmoil that peace could be achieved.

Ary Scheffer, The Ghosts of Paolo and Francesca Appear to Dante and Virgil, 1855

Ary Scheffer’s depiction of Paolo and Francesca, the well-known doomed lovers from Dante’s Inferno, is one of just several versions. Here, Dante and Virgil look on at an illuminated Paolo and Francesca who have been damned to hell for acting upon their forbidden passion. Despite the lovers’ ardent embrace, it is ultimately an image of despair as the viewer notices Francesca’s tear rolling down her cheek.

Aphrodite, known as the “Venus de Milo,” c. 100 BC

The most famous sculptural representation of the goddess Venus (Aphrodite in Greek) was discovered on the Greek island of Milos in 1820, and thought to be Venus because of her half-nude and curving figure. The elongated torso and contrapposto pose is the very essence of classical Hellenistic art—a period that totally embraced naturalism.

Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, 1819

This dramatic work by Géricault depicts an actual French shipwreck that happened off the coast of Senegal in 1816. Created during the Romantic period, it was quite controversial for depicting such gruesome corpses. Géricault showcases the desperation and hope of the sailors to be rescued with the tallest figure, a black sailor, raising his arm in distress.

Paolo Veronese, The Wedding Feast at Cana, 1563

Veronese is known for creating large banquet scenes with immense detail and The Wedding Feast at Cana is definitely a grand affair. The scene is from a biblical event in which Christ (the central figure at the large table) transforms water into wine when the wine runs out during the festivities. Veronese adds his own spin on the narrative by transforming the setting to a Venetian palazzo, altering the religious undertones with a secular vision.