Why The Artist Pension Trust Pulled 18 Lots from Sotheby’s Sale

The recent withdrawal of works from the trust questions the investment model

In 1973, art collector Robert Scull famously sold a Robert Rauschenberg painting, Thaw, for $85,000 which he had only bought a few years earlier for $900. Rauschenberg was so furious that he stormed into the Sotheby’s Parke Bernet auction on Madison Avenue and shoved the collector in frustration. It’s not an isolated incident: For decades, contemporary artists have often been left out of the art market’s soaring price appreciation of their work while collectors have gotten richer.

But a ground-breaking art investment fund that aimed to solve the problem—a kind of retirement fund for artists—hit a huge bump at auction last week. On April 12, Sotheby’s pulled 18 artworks off the block in London that were being sold by the Artist Pension Trust. The London-based Trust lets artists—and, not incidentally, other for-profit investors backing the fund—buy into a portfolio of artwork on the principal that the artists who hit it big will cover the cost of them all. Artists donate 20 works over time and share the proceeds from eventual sales.

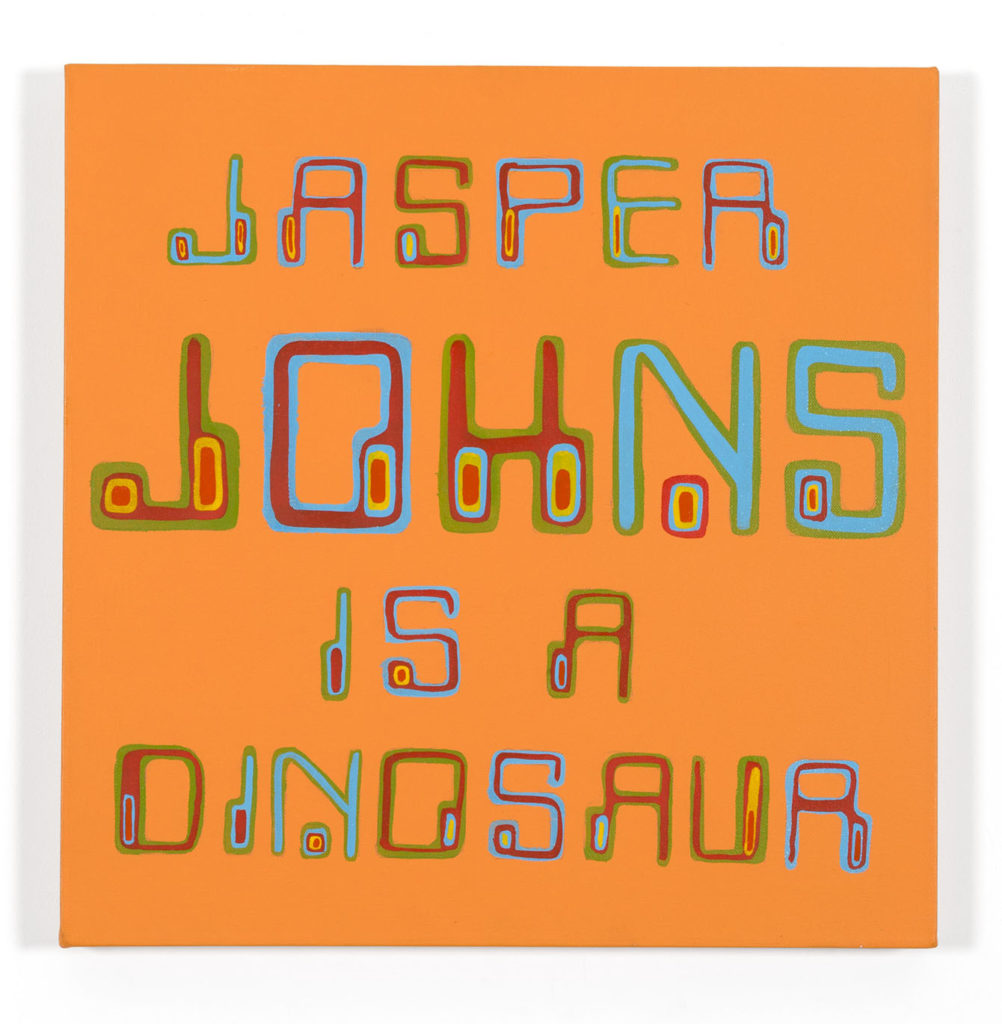

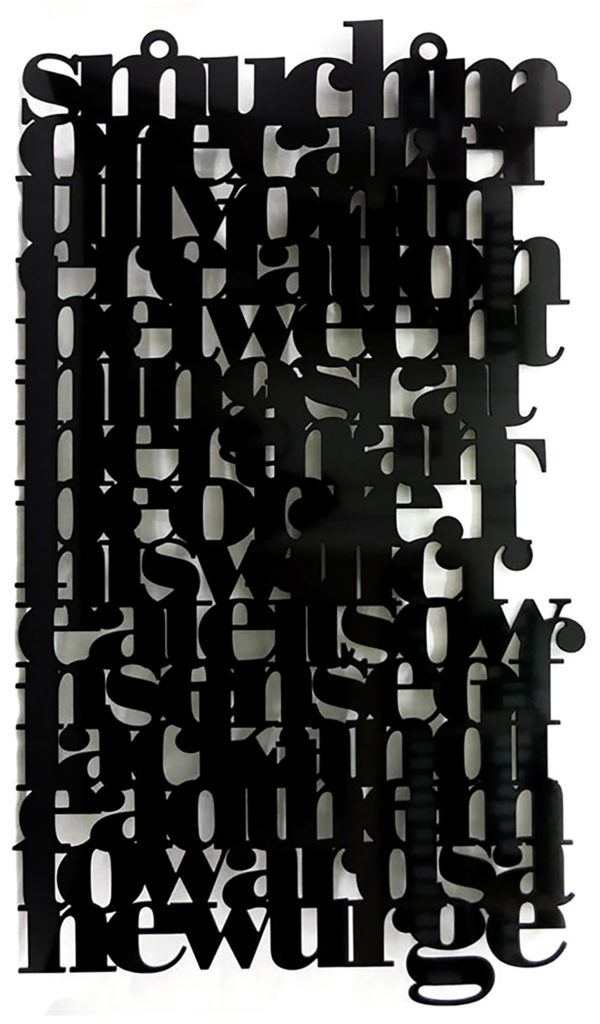

The arrangement is meant to “give artists some security, the ability to stick with what they are doing,” says Al Brenner, CEO of MutualArt, which merged with APT in 2015. But the lots, which included works by two Turner Prize nominees (Liam Gillick and David Shrigley), were unexpectedly withdrawn, as first reported by Colin Gleadell of the Telegraph, amid concerns by artists and their dealers. It was only the second time since its founding in 2004 that the APT had headed to the public market.

In March, APT tried a New York sale of 15 works, also at Sotheby’s. The results: respectable, but no house on fire. Of 15 works, all but one sold. The total was $231,250, in the middle of the Sotheby’s pre-sale estimate of $169,500 to $249,900. But the total includes the auction house’s roughly 20% commission, the pre-sale estimate didn’t.

There’s been “a lot of hoopla” over art investment funds, says Victor Weiner, who for years served as the executive director of the Appraisers Association of America. Bar a few exceptions, they have not done particularly well, he notes.

So far, the Trust “isn’t profitable, in terms of cash flow,” because private sales didn’t even start for about a decade after inception, notes Brenner. But in terms of assets it is: The Trust has amassed a massive collection—nearly 13,000 works, including some by artists with growing global reputations like Rashid Johnson, Daniel Arsham, and Pawel Althamer.

Historically, it’s quite rare for art to be in a pension fund. The British Rail Pension Trust famously sunk about 2.5% of its total assets into art in the 1970s and 1980s. When everything was eventually sold, the trove earned a double-digit return in the low teens. Impressive, but that fund had a much broader portfolio than APT, with Impressionist paintings, Tang Dynasty horse statues, and rare books among the best performers.

As for the Rauschenberg story, he had the last laugh. The artist’s reputation and market skyrocketed, in part due to the publicity over the $85,000 price. Scull would have made a much greater profit if he had just held onto that painting for a little longer. Today, 44 years later, the record for a Rauschenberg is $11.1 million.