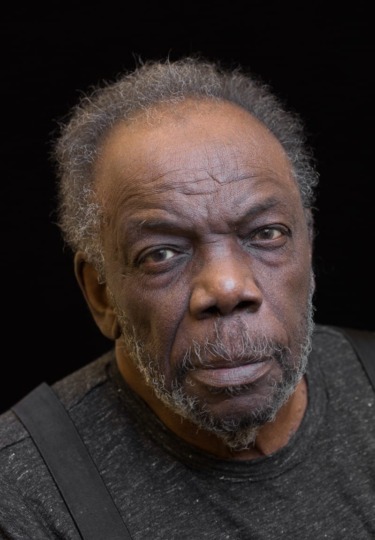

Legendary Artist Sam Gilliam Has Died at Age 88

Galerie looks back on some of the artist’s most significant career moments

After six decades quietly building a respected career, the octogenarian abstract painter Sam Gilliam enjoyed an unprecedented level of attention in recent years, with critical and market attention at an all time high.

When Pace signed him on in 2020, it marked the first time he had been represented by a New York gallery and he showcased a buzzworthy first solo exhibition in Manhattan in November that year.

Born in Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1933, Gilliam moved to D.C. in 1962 and became affiliated with the Washington Color School, a group of color-field painters such as Gene Davis and Morris Louis. A series of formal breakthroughs would eventually result in his now iconic Drape paintings, which expanded upon the tropes of Abstract Expressionism in an entirely new way.

“Each show is a unique experiment and it is only part of a continuum. One show leads to a concept that has to be developed in the next show,” Gilliam told Galerie. “I never work with a single idea, always with the idea that one show inspires another one.”

Below, we look back on some of Gilliam’s key moments with the artist.

Green April, 1969

Sam Gilliam originally garnered attention in the mid-1960s for his beveled-edge and drape paintings, two methods he invented to push the boundaries of what the medium could be. Green April, which was part of a 2018 exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel exploring the link to music, was made by pouring diluted acrylic paint onto the unstretched, unprimed canvas, then folding or crumpling the fabric before stretching it on a bevelled frame after the paint had dried.

Lady Day II, 1971

This monumental 1971 work, also showcasing his pioneering paint-staining technique, set his auction record when it sold for $2.2 million at Christie’s New York in 2018.

Seahorses, 1975

Gilliam’s iconic drape paintings, which were partially inspired by observing women hanging laundry on clotheslines, freed the canvas from the stretcher. One of the largest examples was Seahorses, a six-part work that cascaded across the façade of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. “I never lose the experience of making paintings, whenever I am working with materials,” said Gilliam. “The part of the process that is most exciting is the installation of all the parts into a whole.”

Venice Biennale, 2017

Gilliam was the first African-American artist to represent the U.S. at the Venice Biennale, in 1972, which he considers one of his proudest achievements. In 2017, he returned with Yves Klein Blue, a dramatic draped work that welcomed visitors to the Giardini. Gilliam considers the 1972 presentation one of the proudest moments in his career. “I stayed for three weeks and traveled all throughout Europe, Berlin, Greece and Italy. And I continued to travel through the Art in Embassies program, rebuilding environments everywhere I went.”

“Existed, Existing” at Pace, 2020

Gilliam presented an entirely new body of work during his Pace exhibition. Titled, “Existing Existed,” the show, which took place at both 540 and 510 West 25th Street in Chelsea, featured new large-scale paintings, with some titled as tributes to influential Black figures, spanning from such historical legends as John Lewis to Beyoncé. Visitors also found view new sculptural works that take the form of geometric objects—pyramids, parallelograms, and circles—inspired by the elemental forms of ancient African architecture. Rounding out the paintings and sculptures were a series of monochromatic paintings on traditional Japanese washi paper.

“Each show is a unique experiment, and it is only part of a continuum. I never work with a single idea, always with the idea that one show inspires another one,” he says.

Dia Beacon, ongoing

In 2019, Dia Beacon launched a long-term display of the artist’s work from the ’60s and ’70s, transforming the art foundation into a Technicolor dream. Riding the recent wave of institutional attention, he was the subject of a major exhibition at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Spring 2022, his first museum retrospective in the United States in fifteen years.

“I can build according to any space I exist in. No work is ever shown the same way again. So it goes from unit to environment and I work with the unique object plus its environmental possibilities,” Gilliam said. “The object is finite but the possibilities that extend through the object are infinite. I am an adventurer.”

A version of this article appeared in the Fall 2020 issue titled “Milestone: Sam Gilliam”.