Picasso Myth Debunked in the Berkshires

“Picasso: Encounters” at the Clark Art Institute celebrates the artist’s creative collaborations and how they influenced his work

Unlike most urban museums, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, situated in the leafy Berkshires of western Massachusetts, saves its blockbusters for summer. Its current one is open only through August 27. Titled “Picasso: Encounters,” it is dotted with rare loans from Paris’s Musée National Picasso, among other institutions—and it wittily challenges one of the more persistent myths about the Spanish master.

Picasso is often thought of as a lone creator, breaking away from working on his masterpieces only for ancillary liaisons with various lovers and absinthe drink-a-thons with rival artists. But this solitary genius myth was probably something Picasso himself was behind. “He was a very controlling person,” says Clark Institute curator Jay A. Clark matter-of-factly. The Clark show challenges that narrative and questions just how solo his practice really was. The exhibition of three dozen works, spanning nearly seven decades, looks at how collaborations with artists and printmakers—plus the women who starred in those often-stormy love affairs—influenced his work.

The well-established Clark was founded in Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 1955 by a Singer sewing-machine heir and his wife to display their idiosyncratic but eye-popping collection of such masters as Renoir and Degas. A series of ambitious expansions in the last decade—including a 2014 addition designed by Tadao Ando and a reinstallation by Annabelle Seldorf—has brought the institution onto the national stage.

The expansion of its neighboring institution, the mammoth Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, which opened its sixth exhibition building in May, has also helped direct the art world’s attention to the region.

For these reasons, “Picasso: Encounters” is likely to get lots of traffic. But the show is not without its drawbacks. The exhibition seems shoehorned into a space too small for it; the portraits seem to beg for a few more inches breathing room on each side. And academic curators can sometimes forget that black-and-white prints, which make up the bulk of this show, don’t create the immediate connection that one-of-a-kind paintings drenched in color do.

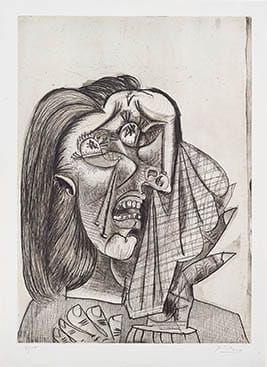

Even masterpieces like Picasso’s “Weeping Woman I-IV” series from 1937—breathtaking in their ferocity and ambition—can’t help but recede when hung next to an oil painting of the “weeping” woman herself, the Spanish painter’s lover Dora Maar. With her talonlike nails a vivid orange, and skin a supernatural yellow-green, she yanks the viewer’s eyes towards her. Still, the exhibition catalogue provides necessary— and sometimes gossipy—scholarship on which printmakers Picasso felt were too involved with his work, which techniques he preferred, and which collaborators he embraced.

Visitors are likely to be most curious about the artist’s romantic or familial collaborators. Dora Maar is just one the muses showcased in this show. Picasso’s daughter Paloma makes an appearance, as does her mother Françoise Gilot—his lover of a decade. His beleaguered first wife, Olga Khokhlova, is also represented here, and Picasso’s sketch of her glaring sideways is hung pointedly in the Clark’s Conforti pavilion next to one of his fecund mistress, Marie-Therese. In other prints, biblical women including Salome (naked, and with the head of John the Baptist) and Bathsheba appear.

All told, the exhibition is a rare and breathtaking loan from Europe that, for art lovers, is perhaps singlehandedly worth a trip to the Berkshires.

“Picasso: Encounters” runs through August 27, 2017. clarkart.edu