Louise Bourgeois’s Drawings Under the Spotlight

Four institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, are now devoting solo shows to the late artist's works on paper

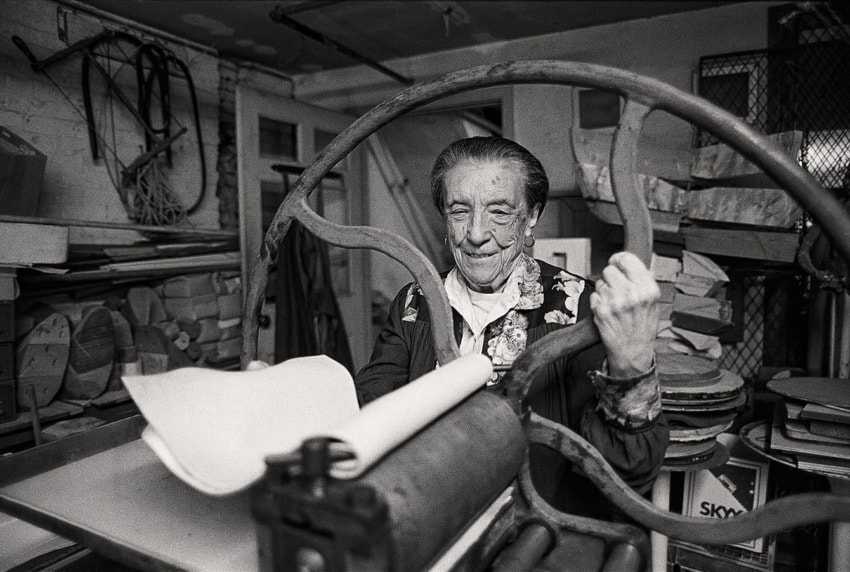

Louise Bourgeois, the celebrated, late French artist best known for her eerie, otherworldly sculptures, drew nearly her entire life. Her parents were in the tapestry restoration business, and she famously recalled of her youth: “I would draw in the missing parts of the tapestry that needed to be re-woven. My ability to draw made me indispensable to my parents.” This early appreciation of drawing as a means to further artistic production—to replication in various media—foreshadowed Bourgeois’s prolific printmaking career.

Four institutions around the globe are now devoting solo shows to the artist, most of them focused on her prints. The largest of these exhibitions, the Museum of Modern Art’s “Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait,” brings together 220 works—a fraction of the 1,200 printed compositions she’s estimated to have made. Altogether, they offer greater insight into Bourgeois’s creative process.

If Bourgeois’s three-dimensional works have long garnered her the most acclaim, MoMA’s Deborah Wye (chief curator emerita, prints and illustrated books, who organized “An Unfolding Portrait”) reveals that the artist felt otherwise: “As [Bourgeois] herself said, for her, there was no ‘rivalry’ between the mediums. Instead they allowed her to say ‘the same thing but in different ways.’ ”

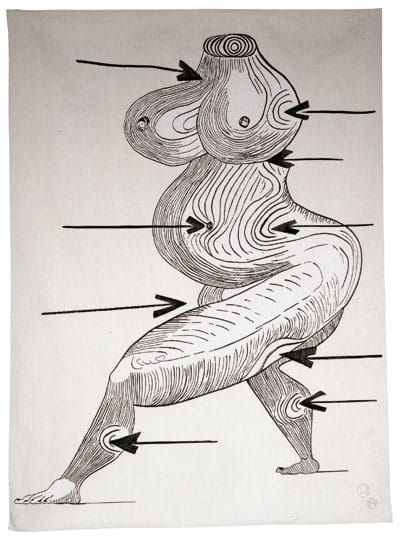

The technique requires an artist to scratch an image into a plate with a needle, the sharp point acting as a pen or pencil tip. Wye highlights one work from her show that employs this technique. In Sainte Sébastienne, a large-scale drypoint from 1992, a “figure is being attacked by arrows that penetrate deep into the musculature of the female body,” she says. “Bourgeois saw those arrows as antagonisms she felt were directed at her. Yet even under attack, the figure strides forward with a bold resistance.”

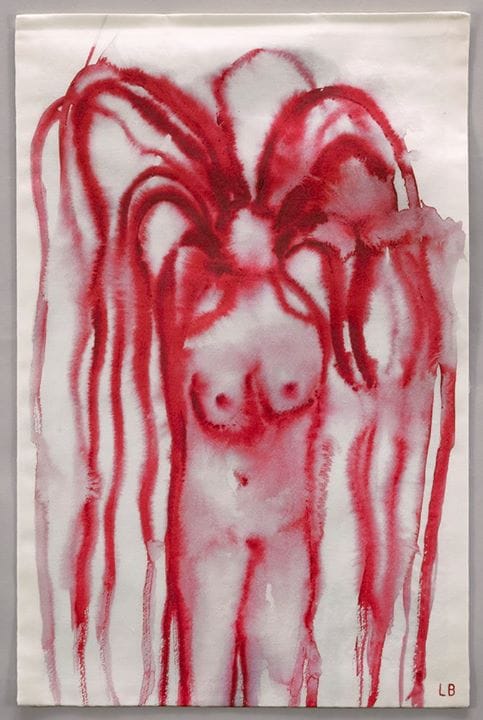

Further, the separation between printmaking and drawing was often indistinct. An installation set titled À l’Infini from 2008, when Bourgeois was 96 years old, is comprised of fourteen nearly entirely abstract etchings overlaid with watercolor, gouache, and pencil additions. “Some figurative elements remain—all suggesting a primordial world. Bourgeois has blurred the line between printmaking and drawing and created a room-size installation,” says Wye.

The other locations hosting Bourgeois solo exhibitions include New York’s Marlborough Gallery (“Louise Bourgeois: Prints”), Tel Aviv Museum of Art (“Louise Bourgeois: Twosome”), and Tel Aviv’s Gordon Gallery (“Pink Days / Blue Days”). The latter marks the first solo gallery exhibition in Israel showcasing the artist’s prints. Here, one of the most remarkable pieces showcases her drypoint technique.

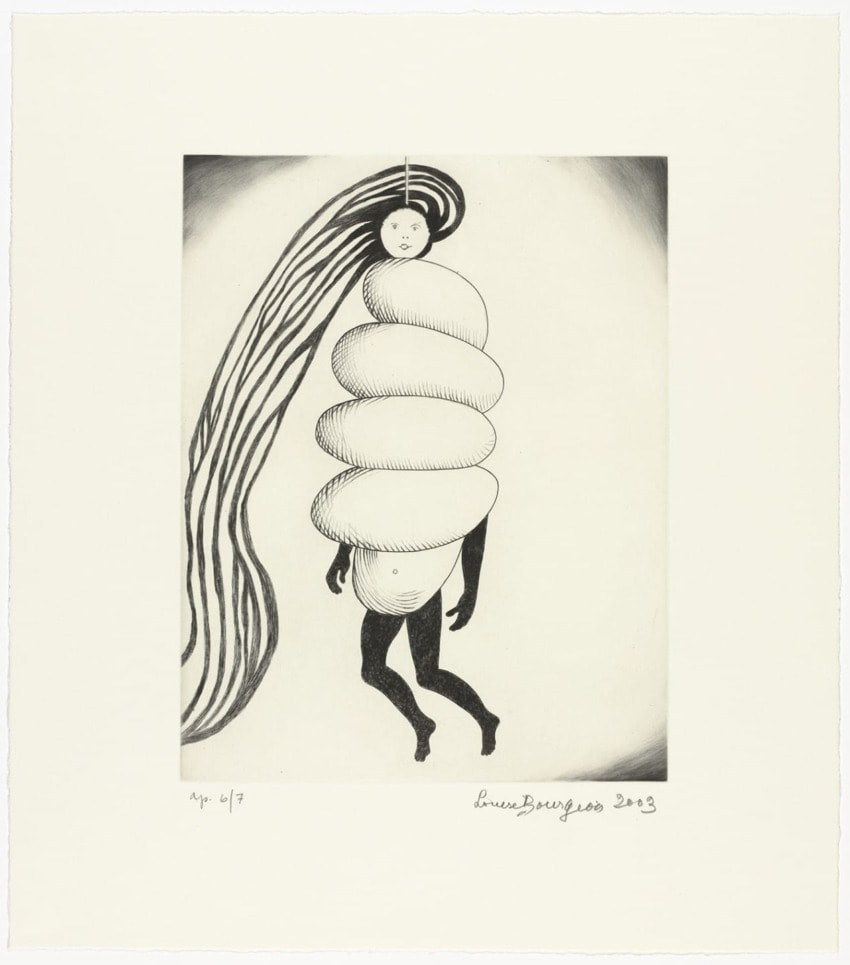

Made toward the end of her life, The Young Girl (drypoint on paper and cloth with hand coloring) depicts separated portions of a nude girl whose branch-like hair extends wildly from her body. The female body is depicted as natural and unconstrained, even against a bleak gray backdrop.

Bourgeois’s works on paper continue to influence younger generations. At the recently opened 15th Istanbul Biennial (through November 12,) her 1947 black-and-white line block print Femme Maison, of a woman’s body with a house on top, hangs on a wall across from a video it inspired. A play on the French word for housewife, the drawing becomes a feminist critique of domesticity. By Italian artist Monica Bonvicini, the corresponding film depicts a real, nude woman with a sculpture of a white house on her head, banging it against two white walls on either side. Ultimately, Bourgeois’s drawing is a means to greater output, art that generously lends itself to further creation.

- “Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art through January 28, 2018.

- “Louise Bourgeois: Pink Days / Blue Days” is on view at Gordon Gallery, Tel Aviv, through October 28.

- “Louise Bourgeois: Twosome” is on view at the Tel Aviv Art Museum through 20 January, 2018.

- “Louise Bourgeois: Prints” is on view at Marlborough Gallery, New York, through October 14, 2017.