How Native Alaskan Culture Influenced Surrealist Masters

A fascinating exhibition at New York’s Di Donna Galleries sheds light on a long overlooked cultural exchange

When Surrealists such as André Breton, Max Ernst, and Leonora Carrington arrived in the United States in the 1930s and ’40s, after fleeing the Fascist oppression sweeping Europe, they found not only refuge from the devastation of their own culture, but also inspiration in a new one.

Native American art and creative traditions, especially those of the Yup’ik people of southwestern Alaska, provided the group with a powerful visual language that allowed them to more deeply explore their already established interests in mysticism, dreams, and the subconscious. While many of the artists eagerly collected Yup’ik ritualistic objects, especially the masks they used to commune with animal spirits, few fans of Surrealism realize the influence Native American art had on the movement.

This is the subject of an extensively researched and visually stunning exhibition at New York’s Di Donna Galleries that pairs 16 rare Yup’ik masks alongside paintings, photographs, and sculptures by the artists who were drawn to them. On view through June 29, “Moon Dancers, Yup’ik Masks and the Surrealists,” reunites many of the masks—which were owned by Breton, Enrico Donati, and Kay Sage, and other Surrealists—for the first time since they were divvied up among private collections and institutions after the artists’ deaths.

Bringing these works into direct dialogue has taken over 30 years for Native American art and antiquities dealer Donald Ellis, who collaborated with Emmanuel Di Donna to realize the show. “A lot of attention has been paid to the influence of various cultures on major movements in modern art, such as the Cubist’s obsession with African art,” he says. “But Native American contributions have been overlooked despite being just as formative.”

Intrigued by the shamanistic ritualism and transformational aspirations of Yup’ik mask making, the Surrealists found new ways to express their own interest in dream imagery, mysticism, and psychic exploration. According to Ellis, every year new mask designs were envisaged by shamans, who then related them to a mask maker. Often combining animal and human characteristics, the completed masks were worn by dancers, who became conduits between the physical and spiritual worlds to guide hunters to food in the dark, sunless days and cold, moonlit depths of the Alaskan winter.

This powerful relationship with nature is evident in a trio of works. A circa 1900 Yup’ik mask depicting a round seal face with large, deep, vacant eyes is displayed near a rectangular bronze sculpture by Max Ernst from 1960 that boasts a lunar-like orb bearing eyelike depressions that hauntingly resemble the mask. A glittering scene painted by Leonora Carrington in 1950, meanwhile, features half-abstracted figures in various attitudes of ecstasy or action that filter the foreground of a flattened and desolate landscape under a gold-leaf moon that hovers against a red sky, much like Ernst’s cold seal-eyed moon.

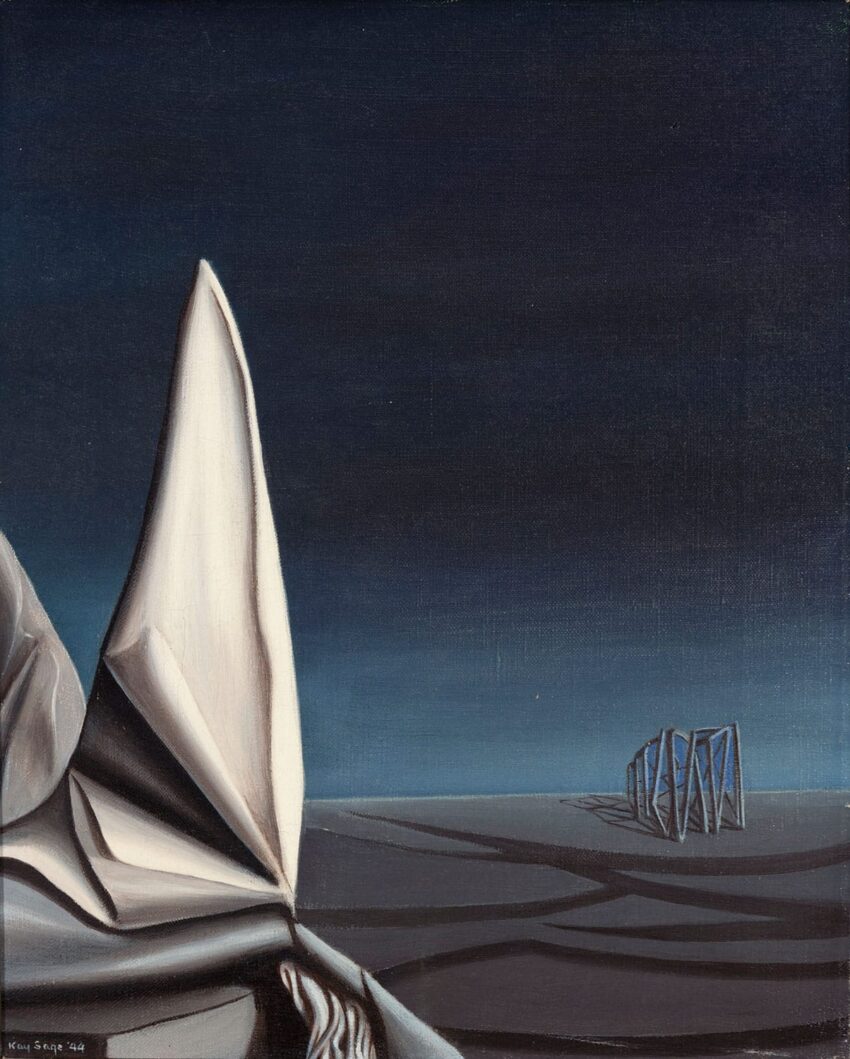

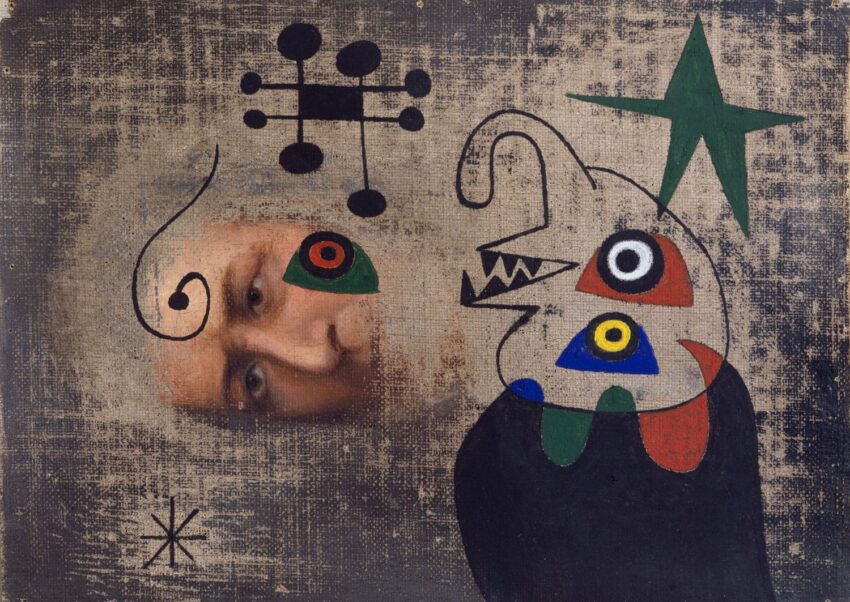

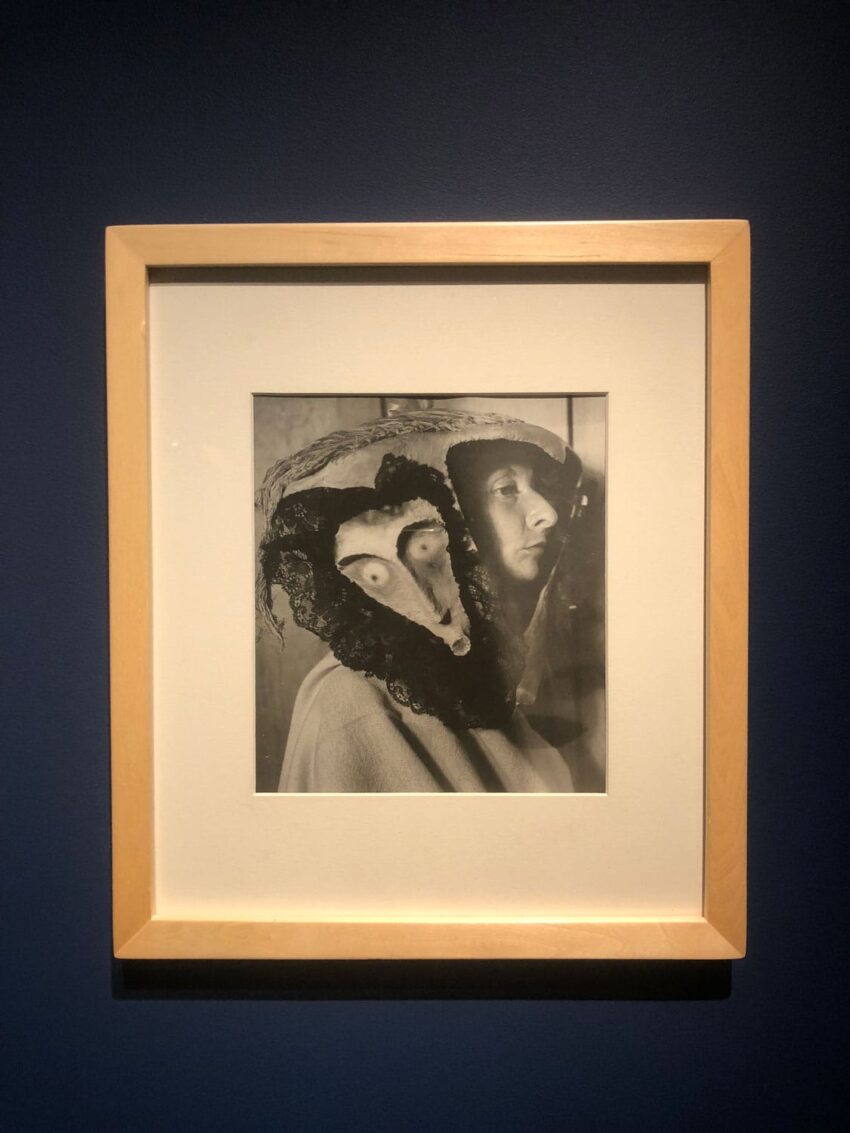

The links between Yup’ik mask imagery and Surrealism is even more readily apparent in pairings such as Victor Brauner’s Germination, 1955, in which his brightly colored half-animal, half-human figures look like they could be painted versions of the geometrically complex Yup’ik mask displayed next to it. Kay Sage directly copied Yup’ik masks into some of her paintings and assemblages, even going so far as to draw a mask of her own in her Design for a Tarot Card from 1944. Other artists integrated the performance of mask wearing into their work, as seen in Kati Horna’s 1957 black-and-white photo of Spanish artist Remedios Varo in a mask made by Carrington.

“The overlap between these artists, and between cultures and interpretations of these symbols, is what fascinated me about this show,” says gallery owner Di Donna, who met with Ellis earlier this year to begin planning the exhibition. “Seeing these masks and these works all together brings a richer understanding of one of the most important movements in the 20th century.”

For Ellis, the Yup’ik masks have their own agency within art history. “These objects have so much beauty and power beyond the Surrealists,” he says. “I look at the mask that Enrico Donati used to own displayed next to his painting Medisance de l’air and think not about how the artist looked at the mask, but about how the mask watched the artist paint that picture.”

SaveSave