Revisiting Richard Avedon and James Baldwin’s Groundbreaking 1964 Collaboration

On the eve of an important exhibition at Pace/MacGill in New York, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Hilton Als discusses why the project still matters

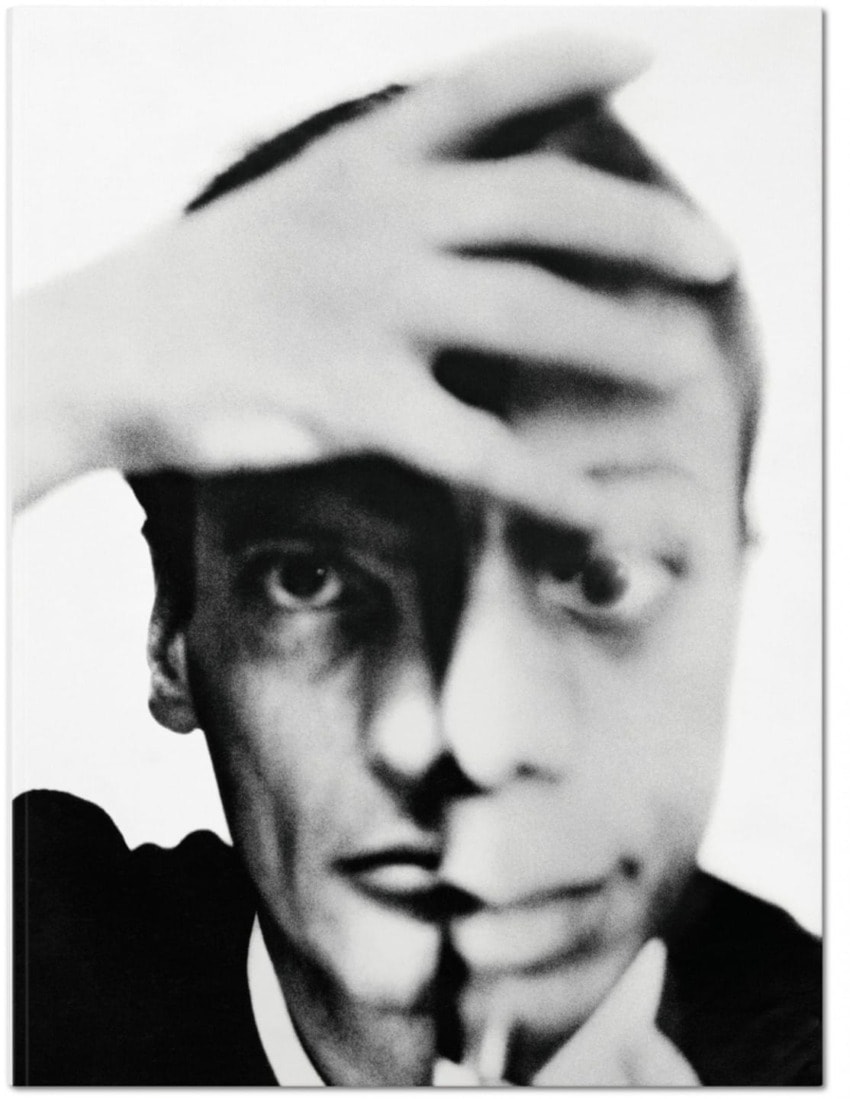

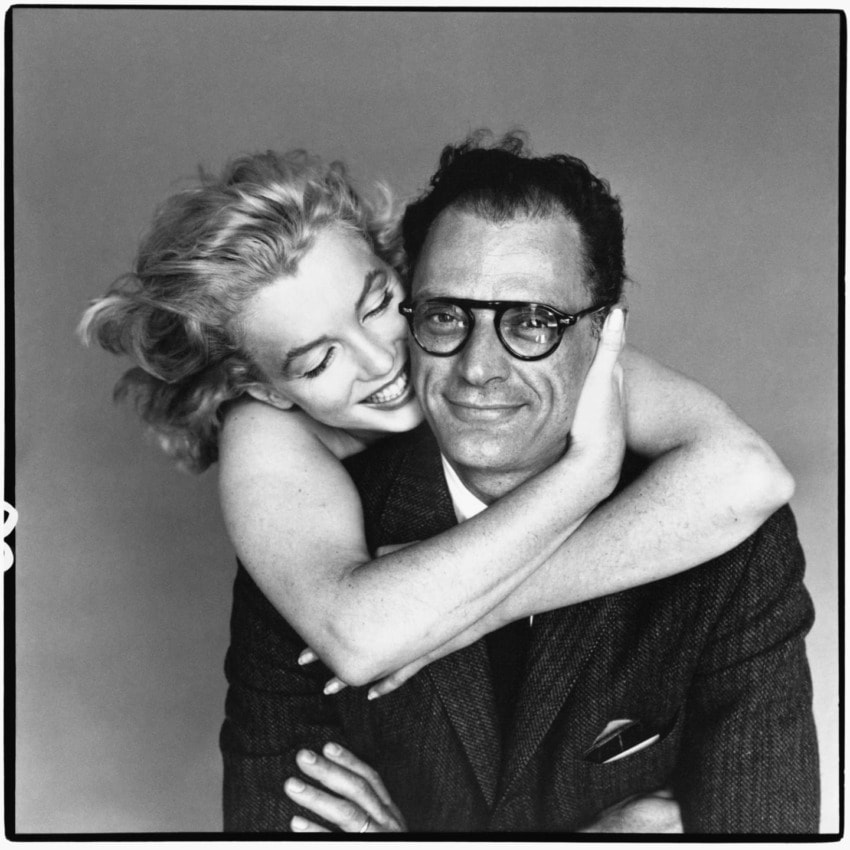

In 1964, two titans of American postwar culture, photographer Richard Avedon and writer James Baldwin, teamed up to produce the iconic book Nothing Personal. It was a radical project, pairing Avedon’s photographs—such as a dazed Marilyn Monroe and a nude Allen Ginsberg—with sober and fiery texts by Baldwin. That legendary partnership, the subject of the show “Richard Avedon: Nothing Personal” at New York’s Pace/MacGill Gallery through January 13, wasn’t the first time the duo worked together. Here, Pulitzer Prize–winning New Yorker critic Hilton Als, who wrote the introduction to a special reissue of Nothing Personal (Taschen, $70), shares their backstory with Galerie contributing editor Antwaun Sargent.

Antwaun Sargent: Avedon and Baldwin knew each other before this book?

Hilton Als: Yes, they met at the prestigious DeWitt Clinton High School in New York City. Avedon and Baldwin both worked at the literary magazine The Magpie. Avedon was the editor in chief, and Baldwin contributed a bunch of stories and poems over the years. Throughout high school, they were really good friends. When they finished school, they planned to do a book called Harlem Doorways. That project didn’t come together, but they always had a dream of collaborating. When Baldwin became supersonic-famous with The Fire Next Time, Avedon was asked to photograph him. They started talking, and Baldwin said he would love to write the text for a book Avedon had in mind.

A.S.: Talk about how you see Baldwin’s texts and Avedon’s pictures working together.

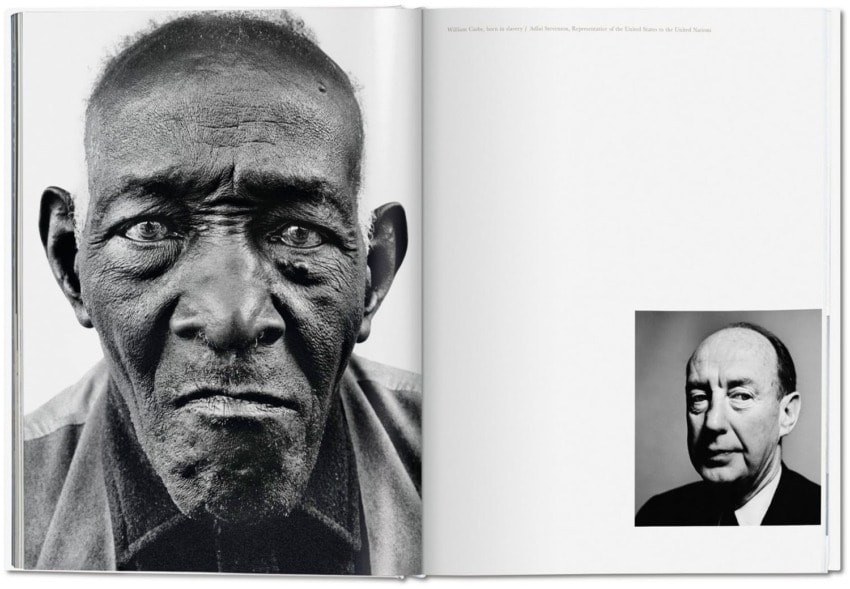

H.A.: Originally, Baldwin wanted the book to be called Crime Is Punishment. Avedon said no way, and Baldwin was like, “Well, it’s a good title.” Baldwin’s text is really one of the emotional spines of the book. It doesn’t speak directly to Avedon’s works, but rather to the times. It’s divided into four sections, and the first section is Baldwin watching TV and seeing how his country is reflected in its advertising. The second part is about when Baldwin was arrested, and the third and fourth sections are a general plea for a kind of emotional and social integration to take place in America in order for the country to survive. In the end, to get Baldwin to finish the project, I think Avedon had to lock him in various hotels in Paris and Finland.

A.S.: Describe your introduction for Taschen’s new edition of the book.

H.A.: I talk about the way the book mattered to me growing up, because it was one of the first examples I ever saw of how words and images not only support each other but really reflect each other—and it doesn’t have to be a direct semblance. It can be a real sort of admixture of sound and image, you know?

was born a slave, and Adlai Stevenson. Richard Avedon, © The Richard Avedon Foundation

A.S.: Can you discuss more specifically what Avedon’s and Baldwin’s art meant to you?

H.A.: The way in which Avedon redefined portraiture and fashion pictures was an enormous inspiration for me. And he was one of the first people, when I got to The New Yorker, who was very interested in me. Baldwin really spoke to my soul. He spoke to the person—a queer person—who had come from economic circumstances that were not so different from his. He had this way of saying that you could go somewhere, become yourself, and still be connected to people you love. It was an enormous revelation. pacemacgill.com; taschen.com