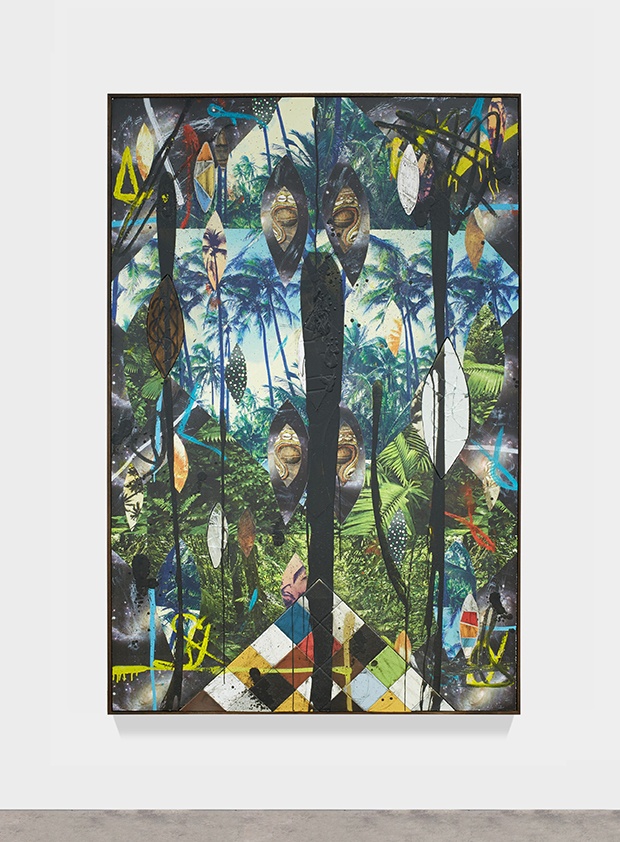

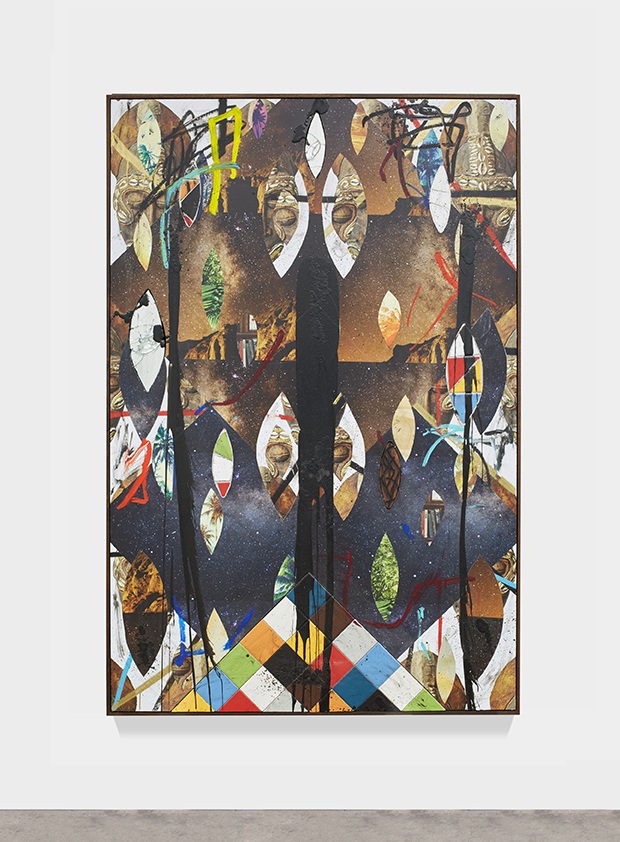

Artist Rashid Johnson works in a broad range of media including painting, sculpture, drawing, filmmaking, and performance to explore personal narratives and common cultural identities, often challenging the assumptions prevalent in shared notions of blackness.

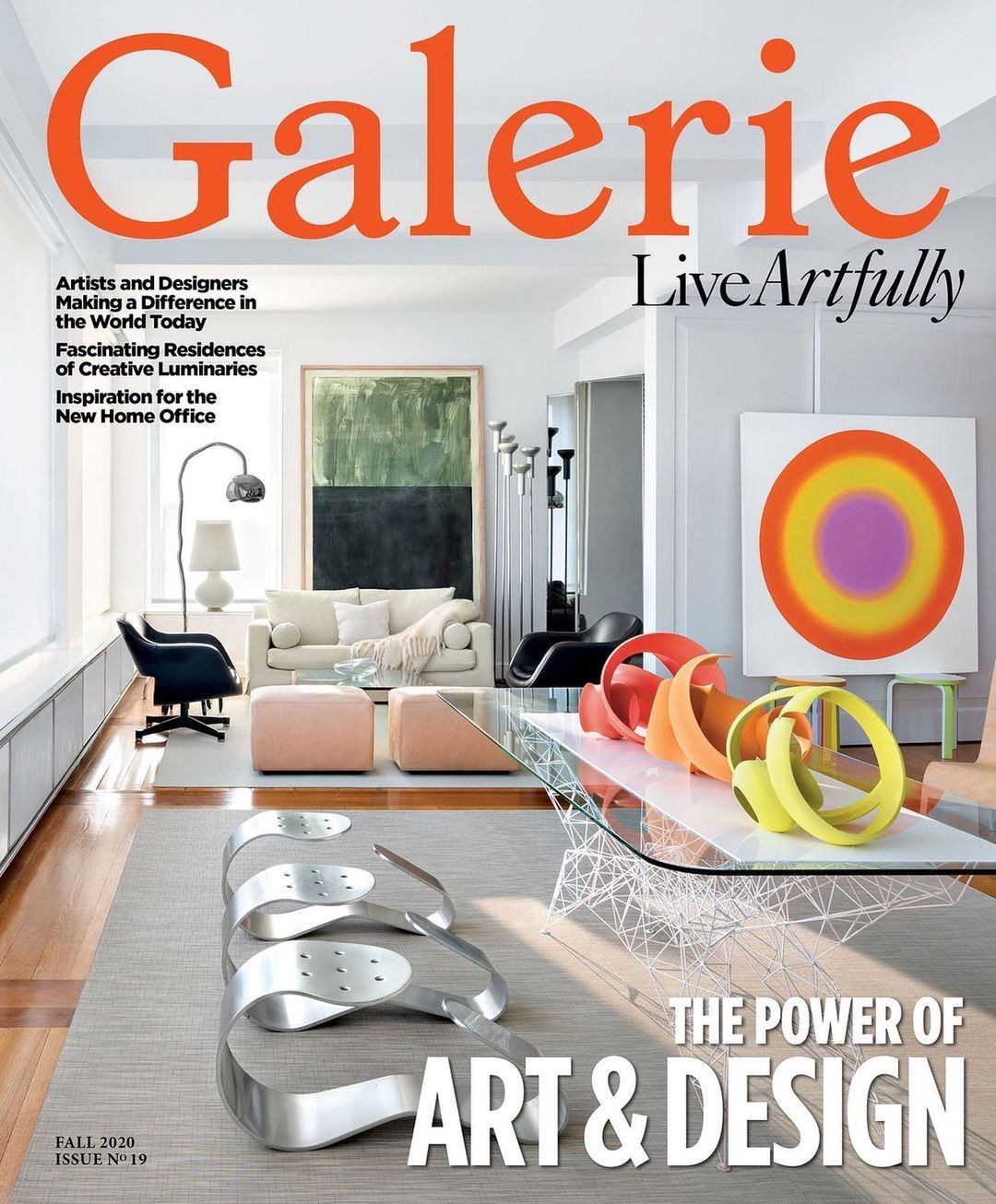

In early July, Johnson’s solo exhibition will open at the Aspen Art Museum (AAM). Presented in partnership with the Museo Tamayo in Mexico City, the show will debut four collage-based works as well as a major new commission (he was the winner of the 2018 Aspen Award for Art), an installation featuring live performance and video.

In August 2018, on the occasion of artist Rashid Johnson’s being honored with the Aspen Award for Art, the artist did an interview with AAM’s CEO Heidi Zuckerman. Here is an excerpt of that interview. Take a look at Johnson’s daily 5-Minute Journal for Galerie here.

Heidi Zuckerman: The idea of empathy is really important in your work, too, can you talk more about that?

Rashid Johnson: It’s huge in my work, but it’s huge for all of us. Being empathetic and caring about others is really the most important thing that we can do, collectively. Some of the material I’ve employed in the past, like black soap—a West African material used by people with sensitive skin—becomes an empathetic material by addressing the idea that somebody out there needs this material to get clean without having skin issues. It’s the same thing with material like shea butter, which you put on your body to moisten and rejuvenate it.

These materials begin to speak to the idea of empathy. Generosity and empathy are also married to me. An artwork can give something back; it’s employable; it gives an emotional resonance and a physical opportunity—whether you participate with it in a physical way or as a viewer. I frequently think about how empathy functions in my work and in the work of a lot of different artists.

Recommended: 5-Minute Journal: Artist Rashid Johnson Opens His Diary for Galerie

Zuckerman: One of the things I think and talk about a lot, and sometimes ask other artists about, too, is how much we need from art. You talked about what art can do. How do you balance that responsibility, as you’re making art, between people needing art to do or be something and allowing it to be everything and nothing, simultaneously?

Johnson: Art can very easily do both. My artwork is intended to be read as an object dealing with the antecedent in our history, with how mark‑making, gesture, and material have existed historically. There’s a second, maybe more rigorous component in which I begin to think conceptually about how those materials, marks, gestures, and ideas, in my hands, become different from artists who may have employed similar things in the past.

It’s dangerous to imagine that art has a job. When we think of art as having a job, we’re putting a weight on it that is unfair to artists as well as artworks. Having said that, it’s a capable tool, and it’s, oftentimes, a slower tool. My wife talks about how great art can come from difficult times. I’m not positive I agree with that. I don’t think that artists are so lazy that they need calamity to make something interesting. That’s a problem. And most art that responds directly and quickly to more problematic issues tends to be fairly anecdotal, didactic, and legible in a way that lacks a certain sophistication.

Art has this incredible ability to make change over a long period of time. It seeps into the culture slowly and aggressively. Literature is a great example of this. Something as simple as a book by James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time, which is clumsy, crazy, tough, and hard, but fifty, sixty, seventy years later, we’re thinking and talking about it and its effects. We might be learning more from that book today than we learned from it when it was originally published.

A similar thing can happen with a painting or a sculpture. We can learn something from it after it was made, perhaps a long time after—maybe through the physical change of the artwork, like in the case of the patina. We all think we know Jackson Pollock, but only a few of us saw a Pollock when he made one. It lived as a different object than what we witness today. The way we interpret, look at, and participate with that object is different. The way we’re being affected by it is an interesting thing to negotiate as an artist and as a viewer.

Zuckerman: I feel compelled to ask if, through your art, your words, and what you’re putting out in the world, you hope to be aspirational?

Johnson: I never really thought much about being aspirational. Is that a dirty word?

Zuckerman: No. It’s a word that involves a lot of personal responsibility.

Johnson: It does. If that is the result, then I accept that today. Today is a good day. Tomorrow, eh, who knows? I like the idea that my work or my presence could be aspirational.

Zuckerman: It’s a time when we have to step up and step into that responsibility that comes from putting things out in the world and the role that culture needs to play.

Johnson: I agree. Absolutely.

Zuckerman: What role do living objects, like plants, play in your work?

Recommended: The 5-Minute Journal: Artist Amy Sillman Opens Her Diary for Galerie

Johnson: I always thought it was interesting to make something that people had to take care of. We all have to keep this thing alive. We have to water this thing. We have to sing to this thing. We have to give this thing love. I was obsessed with Marcel Broodthaers, with his use of plants and the idea of poetry and plants. Places like the Museum of Modern Art used to have plants in the galleries. There would be a potted plant in a de Kooning show—it was such an interesting thing. Where did that go? Whose job was that? Was that the curator who decided they were going to put the plants in there or was that the plant guy at the museum? I was fascinated by it.

So the living things have an art historical footnote as well as this interest in our responsibility for a material, to keep something fragile alive, to participate and engage with it on different levels. Fragility is so interesting to me. When I cast my film, I didn’t want to bring in a big, strong guy; I wanted a thin guy, someone you think is fragile. It’s not that often, particularly in the case of black males, that we get to negotiate this idea of fragility. We always see these examples of strength or guys who are six foot eight and 250 pounds. If I can start to paint a different picture about this idea of fragility and what the black male character can be, I can build a character negotiating difficult psychological terms—I call it Negrosis; some of you call it neurosis. There’s this complicated thing happening in their heads. Oftentimes, we’re not digging into those interesting, engaging crevices, because we’re not imagining those people as being fragile.

Zuckerman: I am grateful for this conversation and your openness to talk about things that are so true. Specifically, the idea of fragility and acknowledging what it is to be fragile. Within that, there comes some freedom. Art and life, it all comes together. Thank you very much.