Photographer Francesca Woodman Is the Subject of Two Groundbreaking New Shows

The exhibitions at Gagosian and London’s National Portrait Gallery aim to change the narrative around the transcendent photographer

Lately the art world has been in a reevaluation mode, looking to the past to see what has been overlooked or misinterpreted. This reexamination is why photographer Francesca Woodman is the subject of two major shows in March—one at Gagosian gallery in New York and the other at the National Portrait Gallery in London—that will reframe and enrich our views of her landmark oeuvre.

Woodman, who died in 1981 at age 22, is already renowned for having one of art history’s singular careers. The daughter of successful artists Betty and George Woodman—Betty in particular rode a crest of late-career fame for her ceramic sculptures—Francesca was raised partly in Colorado, attended Andover in Massachusetts, and made much of her work while a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, moving to New York after college to make it as an artist. After

her death, her photography was discovered and championed by critics, and she became posthumously famous, with feminist scholars especially turning her into an icon.

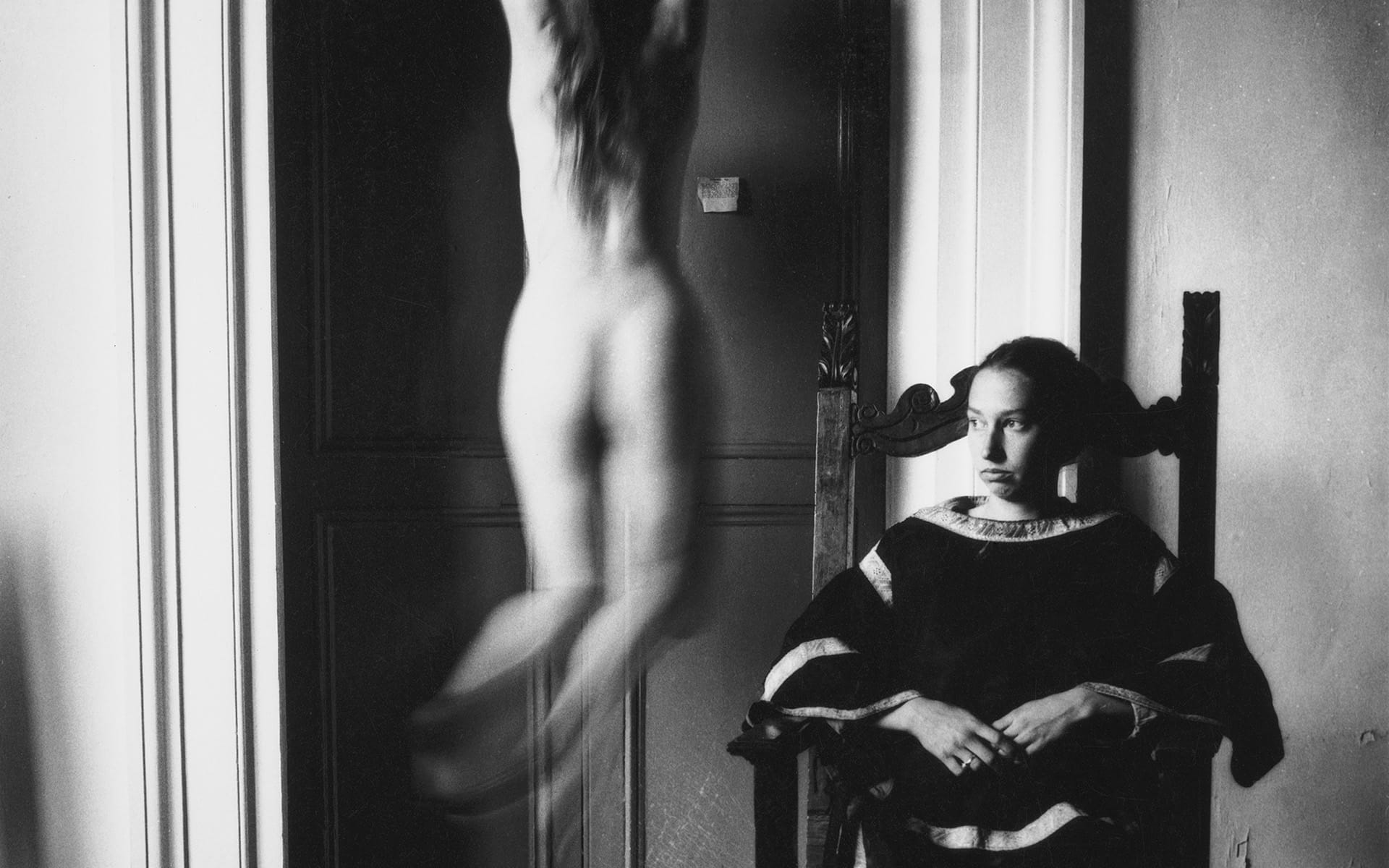

Shooting mostly in black and white and often putting herself in the frame, sometimes in the nude, Woodman created photographs that were stirring, lyrical, and a little mysterious, as likely to focus on a room’s peeling wallpaper or paint as the human figure there.

The fact that Woodman died by suicide colored the interpretations of her images, leading people to see the art as a restless, almost haunted search for identity that ended in tragedy. “There’s been a limited view of her, through the lens of biography,” says Lissa McClure, the executive director of the Woodman Family Foundation, which holds the work of Woodman and both her parents; the president of the board is her brother, Charles Woodman.

In a 1979 draft of a letter, Woodman mused on her classical inspirations and her process. “I try to be intuitive, when I am actually taking the pictures I really only think about composition, not about content [and] meaning,” she wrote. “I try not to force emotions on them.”

McClure emphasizes how in her view, the depictions featuring Woodman herself, often off-center or with her face obscured, are “not really self-portraits,” adding, “Sometimes the figure is just there in service of a larger idea.”

The Gagosian show, opening March 13 and running until April 27, marks the debut of the gallery’s relationship with the foundation (save for a small selection shown at Art Basel last year). It will present 60 images from the foundation’s trove, some of which have never been exhibited anywhere, including Untitled (circa 1979–80), showing a female figure, likely the photographer, wrapped around an architectural column. Everything on display is a vintage print made by Woodman herself. “Many of these are pieces that her parents were not willing to part with, and much of it has not been seen,” says McClure.

Woodman’s parents lovingly attended to her estate until their own deaths—George in 2017 and Betty the following year. “You think you’ve seen it all, but you have not,” McClure says.

Charles, himself a video artist, says that he was “eager to change the terms of the discussion” about his sister’s photographs. “There’s a sense of playfulness and humor in her work,” he adds.

McClure notes that architecture—including the classical spaces of Italy, where the Woodman family spent much time at a house in Tuscany and elsewhere—plays a huge role in Woodman’s work. In Untitled (circa 1977–78), on view for the first time, a woman is seen in the nude from the side but through a window, her body divided by glass panes. “She’s thinking about allegory and the body as sculpture,” says McClure about the image, taken in Italy.

Woodman took pictures of men, too, though they have gotten little attention. Some of those images are in the National Portrait Gallery show, “Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In” (March 21 to June 16), which includes a close-up of a boyfriend, Benjamin Moore, from the late 1970s.

The pairing of Woodman with Victorian photography pioneer Cameron—who produced moody and evocative portraits of friends and family, often in allegorical scenes—is a rich one. The curator who organized the London show, Magdalene Keaney, says that there are “resonances and coincidences” between the two artists. For starters, “they both worked for a short time,” Keaney says, Woodman for about seven years and Cameron for just over a decade. Both used props and staging in a theatrical way, and both mixed areas of focus and blur.

Although the two photographers had obvious differences, “they are both incredible women artists who have influenced later generations,” says Keaney.

Positioning Woodman in the larger sweep of art history, instead of seeing her as a lonely outlier, dovetails with the foundation’s goals: to show her as a serious, thoughtful artist who had fully absorbed her medium’s past, then moved it forward in her own way.

As McClure puts it, “We want to give her voice and agency.”

A version of this article first appeared in print in our 2024 Spring Issue under the headline “Image Conscious.” Subscribe to the magazine.