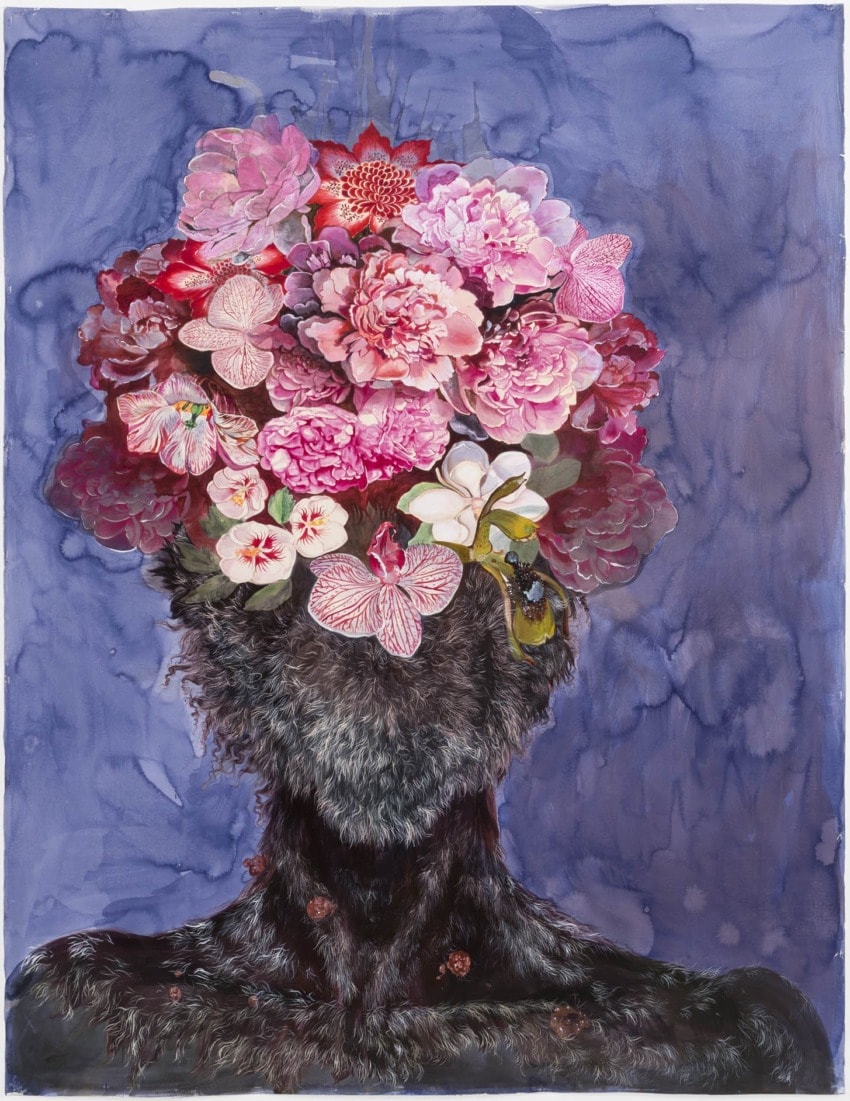

Firelei Báez Tells Powerful Stories with Her Lush Paintings

In the studio with the Dominican-born, New York-based artist as she prepares for a flurry of upcoming fall shows

There are many stories to be discovered in Firelei Báez’s intensely hued, sumptuously detailed artworks. The intricate symbols and patterns that this Dominican-born New York artist weaves into her pieces—whether it’s a 14-by-12-foot painting or a small book-size drawing—are loaded with references from Caribbean history and the African diaspora. Take, for example, her recent site-specific paintings at the “Future Generation Art Prize @Venice 2017” exhibition, a satellite show running in tandem with the Venice Biennale. In an old palazzo, two rococo mirrors were replaced with her portraits of Creole women sporting dazzling red tignons, or knotted headscarves. The works illustrate a time when free black women living in 18th-century, Spanish-ruled Louisiana were forced to cover their hair. Intended to repress, the scarves instead became elaborate, fashionable headdresses which caught on in Europe.

“You’re taught that the Caribbean is a space without history, that you’ve been transplanted there and are at the service of a pleasure complex for others,” Baez says. “I want to claim it back, celebrate, and revel in it.” This interest in challenging history—turning a dark past into something of breathtaking beauty and exuberance—is why Báez, who had her first major solo show at Pérez Art Museum Miami in 2015, is one of the most exciting emerging artists today.

Her narratives are often pulled literally out of history books. Trawling libraries for de-accessioned publications—“those that are no longer morally in line with modern times,” she explains—Báez tears out the pages and adorns them with miniature drawings, paint, and cutouts, revealing her astounding technical skill and draftsmanship.

In her Long Island City studio, Báez is preparing for a flurry of upcoming projects: shows at the Oglethorpe University Museum of Art in Atlanta, Gallery Wendi Norris in San Francisco; a New York MTA subway commission; and a group show in conjunction with Pacific Standard Time’s “LA/LA” at the Museum of Latin American Art in Los Angeles. “There is a vibrant moment for Caribbean art right now,” says art historian and curator Tatiana Flores. “Firelei’s work rethinks figuration and representation in the 21st century, and I can’t think of many who have her drawing talent.”