Behind Cuba’s Rising Contemporary Art Scene

With works as powerful as they are provocative, contemporary Cuban art is having its moment

In 2014, when President Barack Obama announced plans to reestablish diplomatic relations with Cuba, “I started to cry,” says Howard Farber, a 74-year-old former Miami real-estate developer who thought he’d never live to see the day. For the past 16 years, and his wife, Patricia, have built an enviable collection of contemporary Cuban art, among the foremost in the world. They had once been fervid collectors of Chinese art, but a trip to Havana in 2001 shifted their affections. So much so that they founded cubanartnews.org, an online showcase for Cuban art and culture. “I think most people used to envision paintings of Carmen Miranda next to a guy playing a guitar and smoking a cigar,” says Farber.

Such a cliché couldn’t be further from the truth, and since the easing of travel and economic restrictions between the U.S. and Cuba, curators and collectors have spurred something of an art-world gold rush. “This is especially true over the last two years, of course,” says Tobias Ostrander, the chief curator of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, where its collection of contemporary Cuban art will be on view in a show opening June 8. To hear some collectors talk, it’s not strictly the art that holds an allure. The country itself—its architecture, music, political and social history—has them hooked. Philanthropist and collector Madeleine P. Plonsker, whose book on the Cuban art scene, The Light in Cuban Eyes, inspired a 2015 show at the Robert Mann Gallery, puts it best: “When I began collecting the work of Cuban photographers, I fell into a bottomless pit that I never wanted to get out of.”

However, increased demand translates to higher prices. Before more favorable relations, the work of dissident artist Tania Bruguera, who’s been detained by Cuban authorities and stripped of her passport, fetched prices in the vicinity of $10,000 at auction. But in 2015, her sculpture Destierro (Displacement) sold for more than eight times that. Eager as collectors may be, there are caveats. Exporting art from Cuba can be difficult, and forgeries, especially works by great 20th-century masters of Cuban art like Wifredo Lam and Carlos Alfonzo, do exist. The ideal way to acquire pieces is through reputable auctions or from galleries Stateside, among them Manhattan’s Lehmann Maupin, Magnan Metz, Robert Mann, Jack Shainman, and Marlborough.

The interest of such marquee galleries notwithstanding, the chance to start collecting is not out of reach. Although several U.S. carriers offer daily flights to Cuba, tourism has far from crested. “Part of the allure is that one can still discover treasures,” says August Uribe, a deputy chairman of Phillips auction house and an expert in Latin American art.

Some key artists to watch:

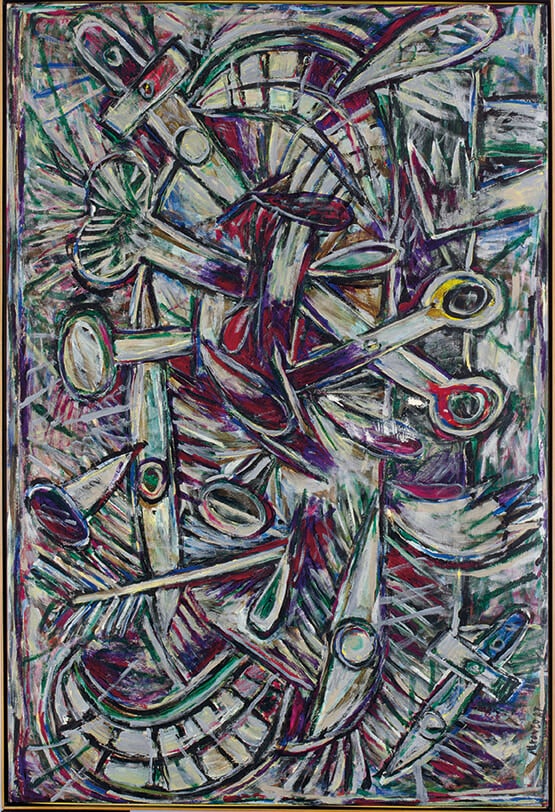

Alexandre Arrechea

Known for his striking public-art installations, Arrechea is a cofounder of the Cuban design and art collective Los Carpinteros, whose members are slated to appear in a host of international solo shows this year. A suite of Arrechea’s giant “architectural” sculptures—each one referencing a famous New York building—lined Park Avenue in 2013. And at last year’s Coachella music-and-arts festival, his 50-foot-high canary-yellow Katrina chairs were on display.

Enrique MartÍnez Celaya

A gifted painter and sculptor whose works are somehow both folksy and edgy, Martínez Celaya left the island at the age of seven and is perhaps the best-known representative of a community of artists who identify as Cuban exiles.

Tomás Sánchez

This painter emerged as a star of Havana’s first art biennial, in 1984. Since then, his prices have climbed steadily, notching above $600,000 at auction. Among the most expensive works of any Cuban artist now living, his lushly painted and detailed landscapes are almost fantastical.

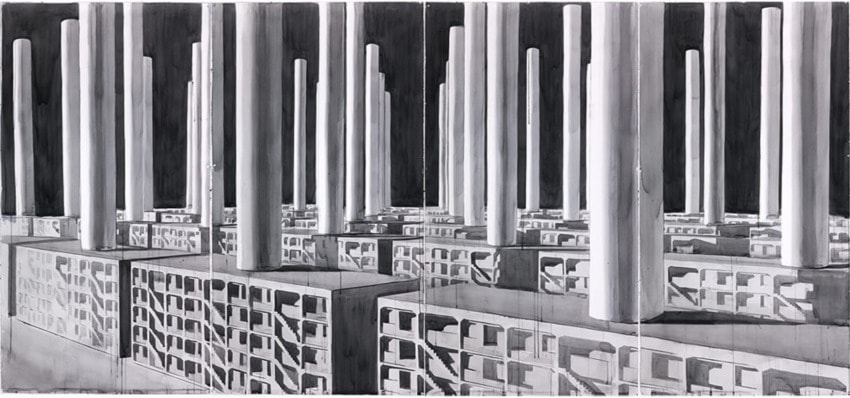

Pedro Abascal

This photographer was dubbed a “stylist of the epic and surreal” by The New York Times and praised for his “ghostly, X-ray-like architectural shapes.” He’s a representative of what curators and collectors consider a recent golden age of Cuban art, the so-called “special period” of economic upheaval following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

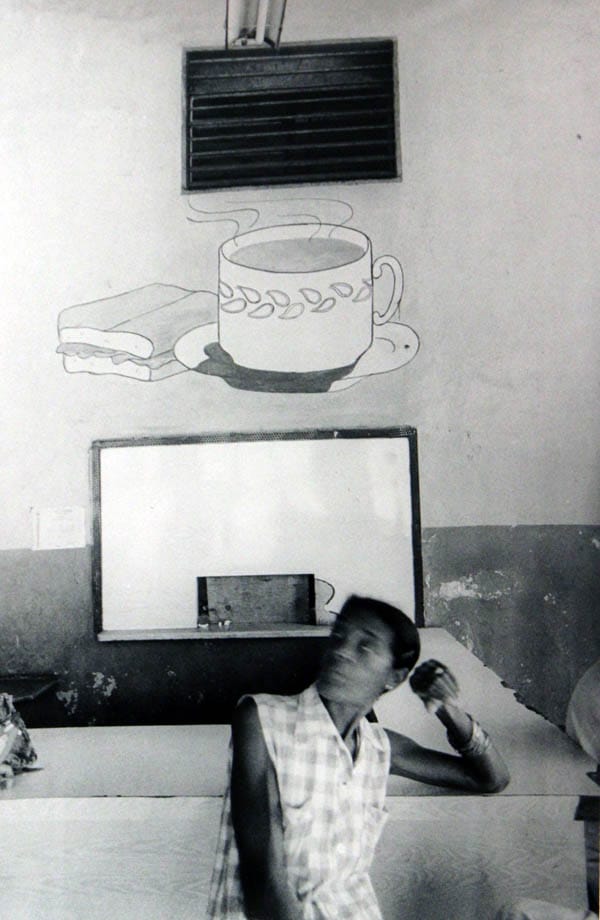

Juan Pablo Ballester

The documentary photographer is known for works with a political tinge. Letters to My Mother, from 1998, shows two hands holding an image of barbed wire. He’s also hired porn actors to portray policemen for his photo shoots. Ballester now resides in Spain, and his work appears in several museum collections, including that of Madrid’s Reina Sofia.