Trace the Evolution of the Cherry Blossom Through Art and Design

How the Japanese symbol of renewal has inspired artists throughout history

In the dreary days of early spring—when the sky is still more lead than azure—plum and cherry blossoms become candelabras that defy the leftover darkness of winter. The effect is brief. Petals fall after a few heavy rains, paving sidewalks, and that canopy lives a second life beneath our feet. Because of their impermanence, hanami—or cherry blossom viewing, a Japanese tradition since the eighth century—is welcomed as a period of reflection on our own transient lives as well as of optimism and renewal. The blossom has inspired countless artists and designers over the centuries. Here, we trace its evolution.

Pink clouds and gnarly branches of cherry blossom trees, or sakura, were a prominent feature in the woodblock prints of Japanese artists like Utagawa Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai and Togaku. Their spectacular visions of the changing season are heightened by lush colors and characterized by an unconventional approach to composition.

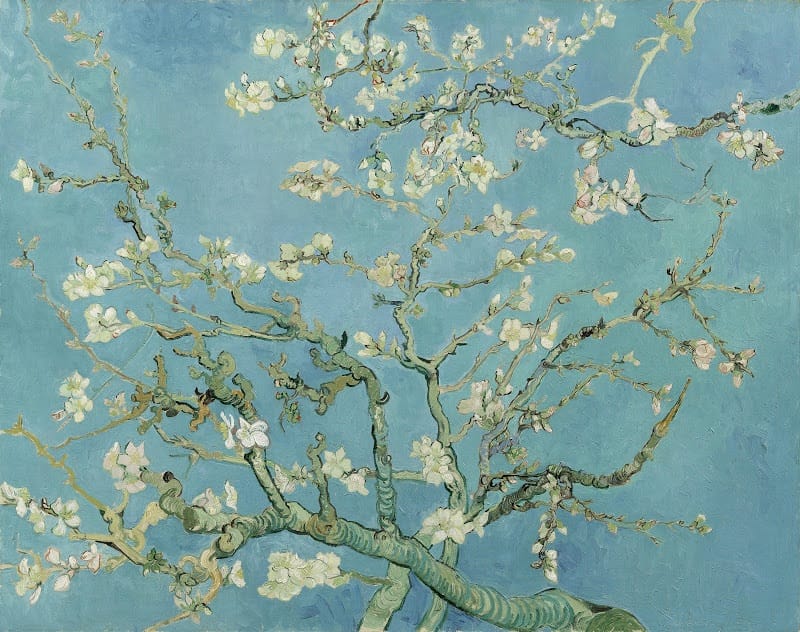

The flower first appeared in the West after the black-hulled ships of Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to reopen to trade in 1853, ending the country’s 220-year-old policy of national seclusion. The art movement coincided with this increased flow of goods from Japan, and these woodblock prints held widespread appeal for European artists, who began to adopt the themes to their own works. The influence can be seen in canvases by the likes of Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Vincent van Gogh, whose famous painting Almond Blossom (1890) features delicate, interlacing branches that closely resemble those seen in Togaku’s Cranes and Cherry Blossoms (1875–1900).

Japonisme, a term coined in 1872 by French collector and printmaker Philippe Burtyhich, came to refer to the incorporation of Japanese themes and iconography into European art and design, and was widespread during the 19th century. Kimono fabric made its way into Victorian fashion and the art of Japanese cloisonné enameling rose to prominence. Pressing sculptured wires into a metal body, colored enamels were applied between them to create dazzling impressionistic images. The vases of Namikawa Yasuyuki, a celebrated master of the medium, depicted flowers of all seasons and were even translated into Sèvres porcelain of Théodore Deck in the 1870s.

Emperor Meiji further supported artistic development using Western technology—particularly from Germany—recognizing the currency value of Japanese arts. In his time, Shibayama—a technique using inlaid mother-of-pearl and ivory—was popular in Europe and took the form of folding carved screens, jewelry boxes, and fans.

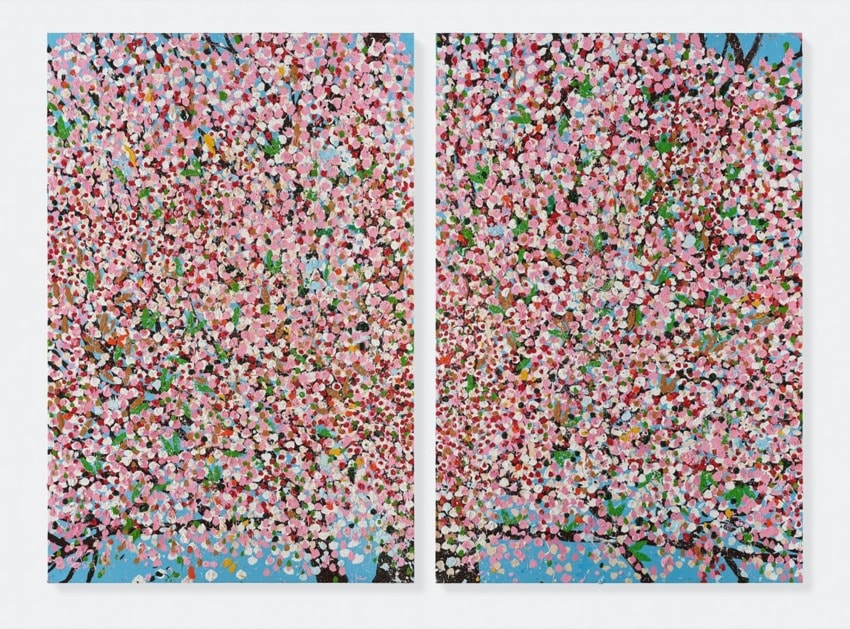

The cherry blossom continues to infiltrate the cultural landscape and inspire creatives everywhere, from Takashi Murakami, who transformed Louis Vuitton’s Monogram handbags with kawaii blossoms in the early 2000s, to Damien Hirst, whose exhibition of cherry blossom paintings at the Fondation Cartier in Paris is slated to open in June 2020.

“The cherry blossoms are about beauty and life and death,” Damien Hirst has said of his new series. “They’re decorative but taken from nature. They’re about desire and how we process the things around us and what we turn them into but also about the insane visual transience of beauty—a tree in full crazy blossom against a clear sky.”