Cartier’s Mystery Clocks: Artistry, Craftsmanship, and Magic

A rare viewing of Cartier's extraordinary Mystery Clocks at the Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie (SIHH) luxury watch trade fair

There has always been an aura of mystique around the Cartier Mystery Clocks. For one thing, the luxury brand refuses to disclose how many of these clocks have been created. Then there is the real intrigue. How do the hands, that seem to float freely in space, actually rotate?

Visitors to the Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie (SIHH) luxury-watch trade fair in Geneva were recently offered a rare viewing of these magical objects in an exhibition setting. 19 of Cartier’s extraordinary Mystery Clocks, spanning 1912 to 1967, were hand-selected by Pascale Lepeu, curator of the Cartier Collection, for a viewing.

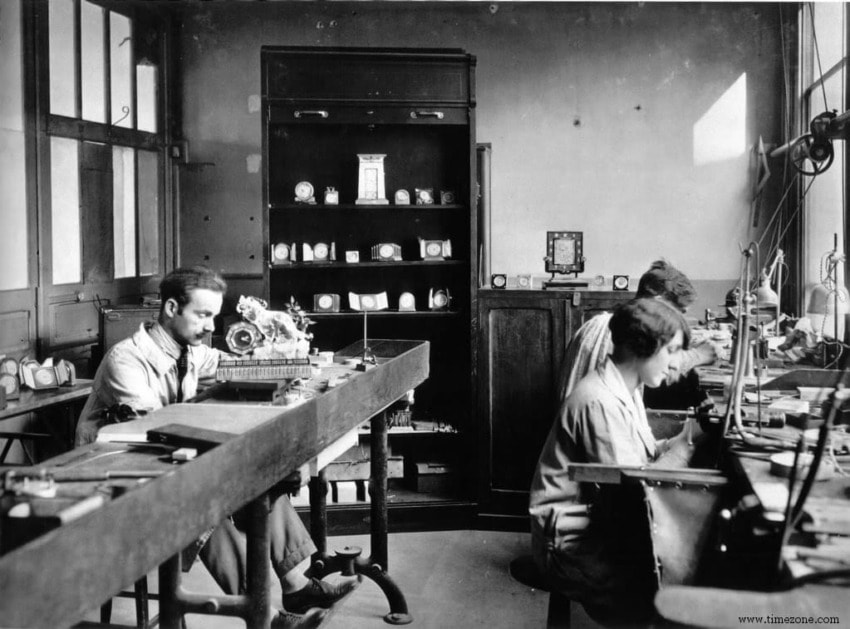

Inspired by the work of the famous French magician and illusionist Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin, each clock—conceived by Louis Cartier and his clockmaker Maurice Coüet—was created to dazzle with both technical and artistic skill.

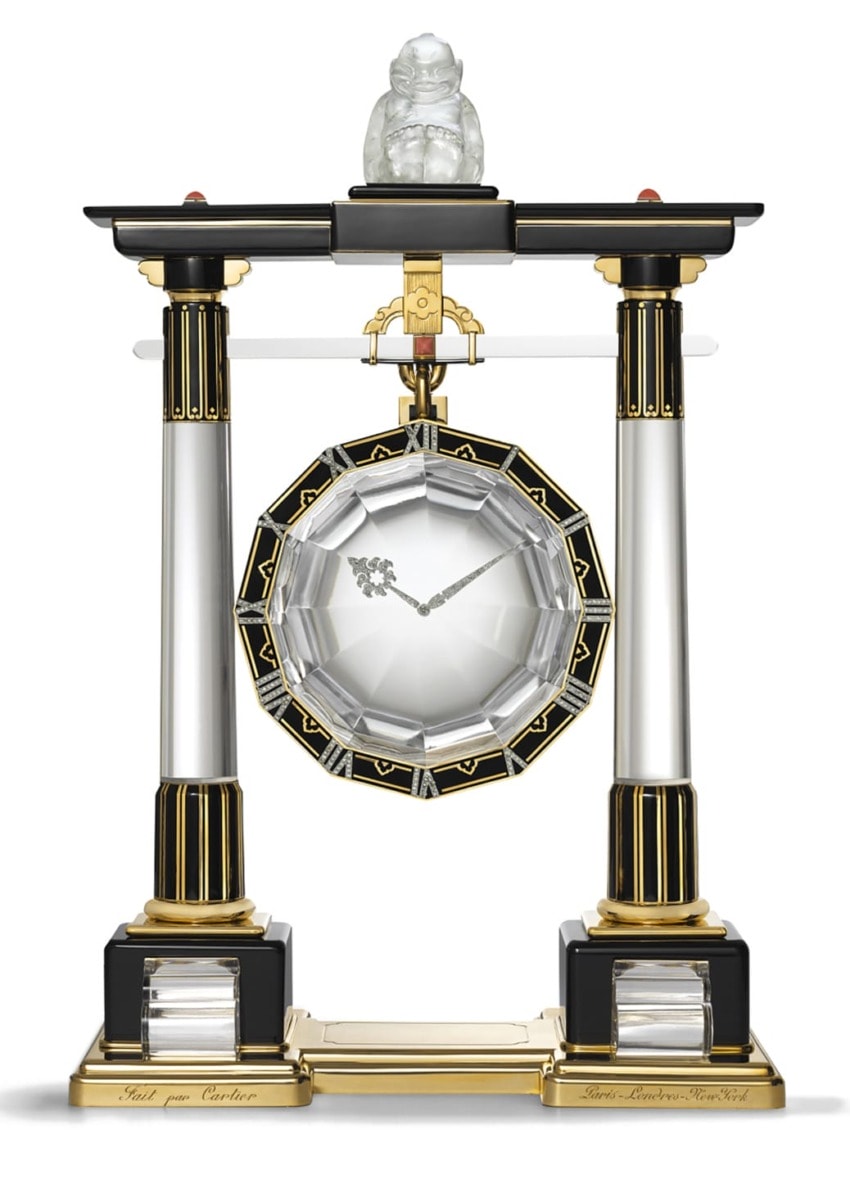

While a certain mystery remains, Cartier is open about their functionality. The hands are attached to two translucent disks that are driven by a clock movement hidden within the base. And because the disks are transparent, they are almost invisible. The watch’s technology was developed more than 100 years ago with the first clock the company produced, the Model A, in 1912. But it’s not just the illusion of space and the groundbreaking technology that makes these items special; these are also bejeweled art pieces that highlight of the mastery of Cartier’s craftsmanship and design skills.

The clocks boast frames of jade, lapis lazuli, mother-of-pearl, coral, crystal, and onyx, while most of the hands are gold and paved with diamonds. The faces are a variety of circles, rectangles, ovals, and octagons. At the height of their popularity, during the Art Deco period, several were designed with the “oriental” themes with materials in vogue at the time. “Cartier was a collector himself and would go shops in Paris to buy antiques with Chinese, Japanese, and Egyptian origins,” Lepeu said. One such object is an 18th-century jade elephant with a clock—framed by a tiny pagoda—sitting on its back. “You have to imagine it would have just been a jade elephant,” Lepeu explains. “Cartier would bring the piece to the workshop and ask the designers to build a clock around it.”

Two of the clocks are known as Screen Mystery Clocks, which depict Chinese table screens, a sign of prosperity for the cultural and educational elite prior to the Qing Dynasty. “It is the shape of the screen the literati had on their desk, and they would look at the screen for inspiration and ideas for their writing,” remarks Lepeu. Following World War II, the change in fashion is reflected in the timepieces. A 1967 clock owned by American heiress Barbara Woolworth Hutton, for example, is made primarily of lapis lazuli and yellow gold. “In the late 1940s, it was all about yellow gold,” she said.

Exceptional provenance, of course, is an ongoing theme. The oldest clock in the collection is a 1914 Model A that was purchased by Henri Count Greffulhe, the husband of Countess Élisabeth (whom Marcel Proust partly modeled his Duchess de Guermantes character on). Another was in the collection of Evelyn Walsh McLean, an American mining heiress and socialite who was famous for being the last private owner of the 45-carat Hope Diamond and the 94-carat Star of the East diamond. And then there was Queen Olga of Greece, who commissioned an “O” and a crown on the base of hers.

The Mystery Clocks are part of the Cartier Collection, which is comprised of more than 1,600 pieces of jewelry, watches, clocks, and precious objects acquired by the luxury brand at sales and auctions all over the world. Parts of the collection are lent out to museums and used for special exhibitions worldwide.