Basquiat: How the Graffiti Artist Became an Art-World Legend

London’s Barbican puts on an unprecedented exhibition of over a hundred works that reveal the artist’s creative process

“Sometimes dreams do come true.” This is the prescient opening line of writer Glenn O’Brien’s film Downtown 81 (1981/2000), starring a brash yet buoyant Jean-Michel Basquiat as a struggling young artist working in a then-dilapidated lower Manhattan. The character wasn’t a stretch for Brooklyn-born Basquiat, just 19 at the time, who was on the brink of his own meteoric ascendancy within the glam and gritty downtown New York art scene of the 1980s.

It is precisely this moment that “Basquiat: Boom for Real,” the much anticipated survey of the artist’s work at London’s Barbican Centre, takes as its starting point. Showcasing many of Basquiat’s works, as well as archival footage of MoMA PS1’s seminal 1981 New York/New Wave exhibition—a 100-plus-artist group exhibition that detailed the city’s downtown counterculture scene at the time—the show immerses visitors into Basquiat’s short but prolific career, just as it was about to blow up.

“He is undoubtedly one of the most important artists of the 20th century,” says Barbican curator Eleanor Nairne, explaining that Basquiat has long been the subject of biographical interest without the benefit of sustained historical analysis. “I felt it was important to create a show that staked a claim for him within a larger context than just his commercial success.”

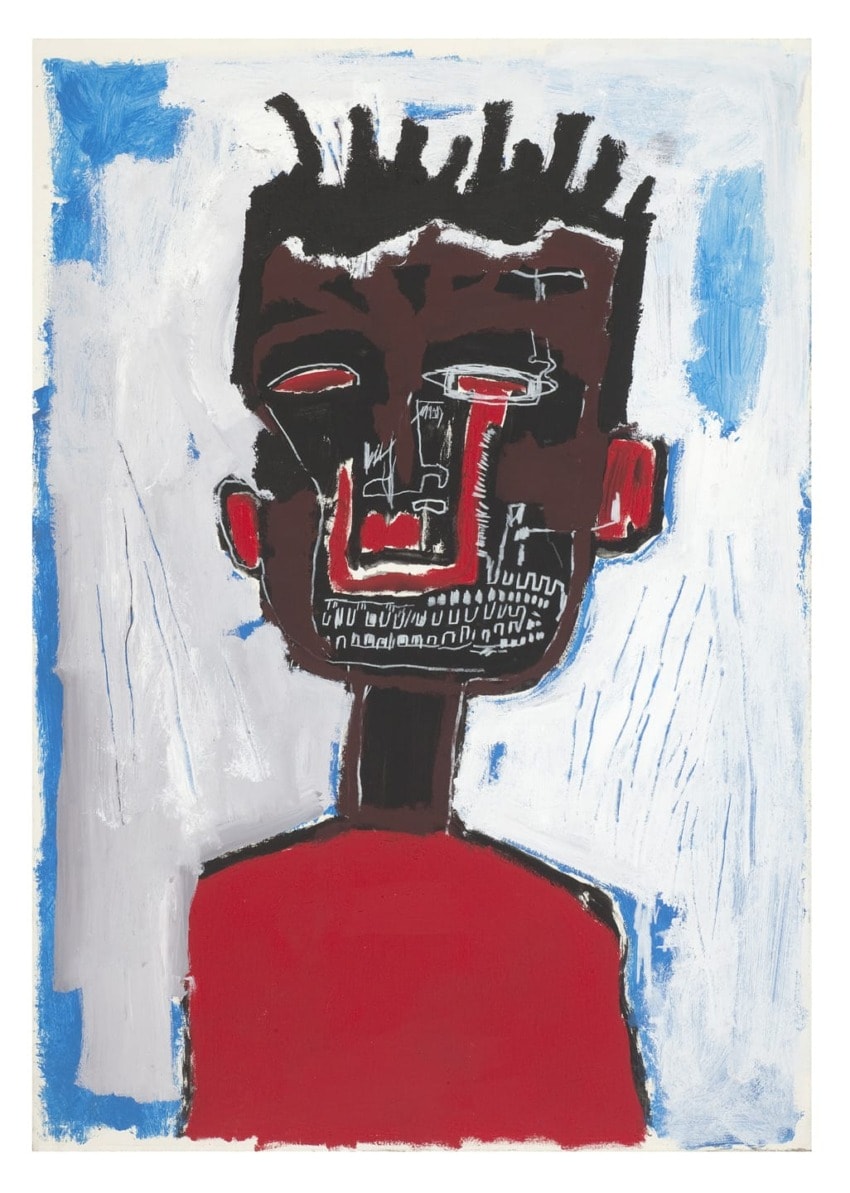

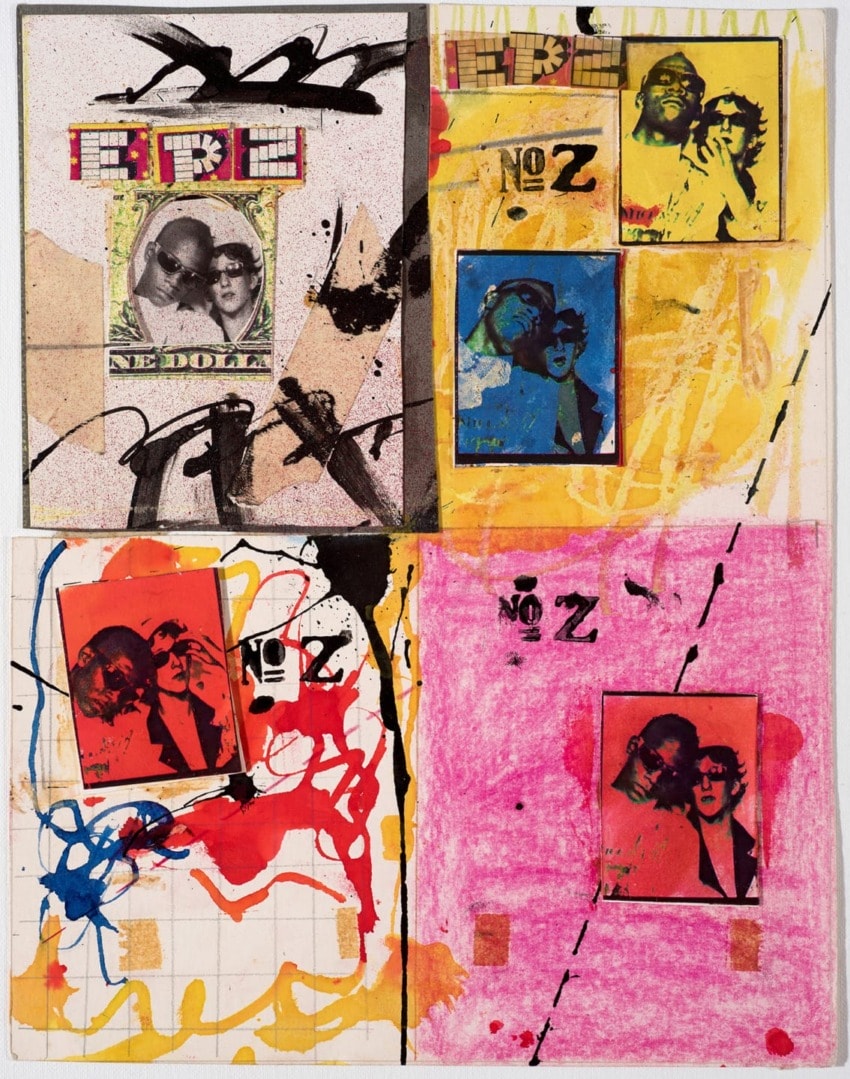

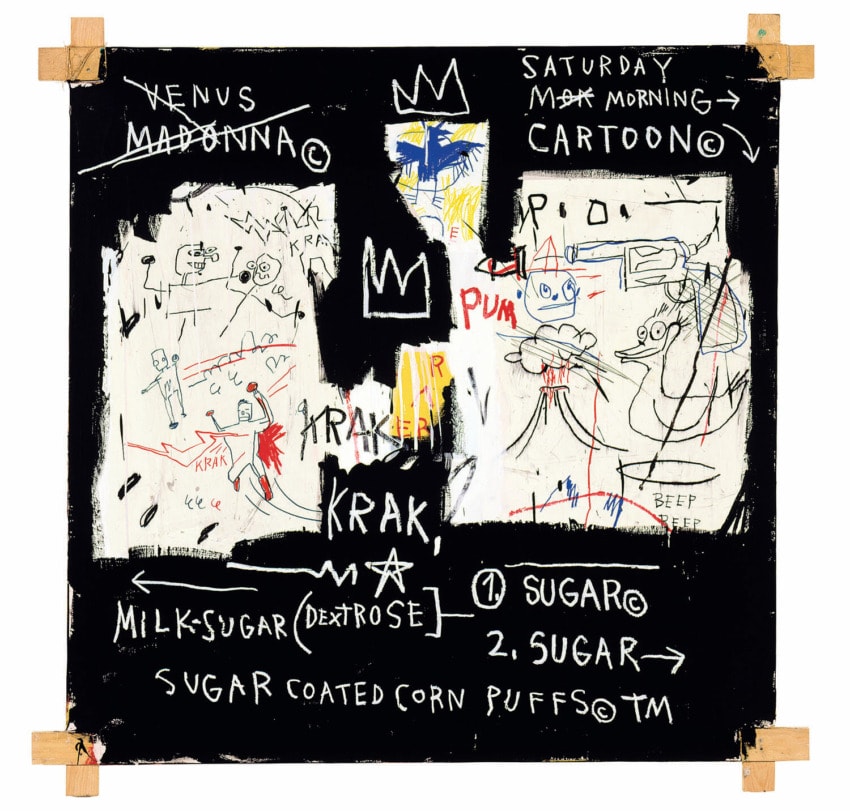

“Boom for Real” is the first large-scale exhibition of the artist’s work in the U.K. with over 100 works, many of which have never been seen in Britain. Split between two floors, the top level chronicles the artist’s start as a street graffiti artist under the moniker SAMO© after he dropped out of school at 16. It then follows his subsequent entrenchment in New York’s hip downtown scene through paintings, postcards, party invitations, and polaroids that place him in the company of his icon and long-time supporter Andy Warhol, artist peers like Keith Haring, writers like O’Brien and Rene Ricard, and celebrities like Madonna.

Basquiat’s background is indeed well-documented and often spotlighted, but according to Nairne, it’s worth reviewing, especially in a non-American, interdisciplinary venue like the Barbican. Because he was interested in and part of so many different creative endeavors—music, film, books, history, pop culture—“there’s loads of source material to pull from,” she says. “It paints a vivid picture of a very different New York City at the time, one that audiences may have heard about but never really seen.”

Beyond the snapshots and sketches of and by Basquiat and his cohort—along with a viewing room for O’Brien’s Downtown 81—archival material tells the mythic story of Basquiat’s ascendance to fame and corresponding astronomic market prices. Documents like the artist’s lease on his Lower East Side studio at 57 Great Jones Street signed by his landlord, Warhol, a letter from Anna Wintour about an upcoming magazine feature, and a contemporaneous Village Voice article detailing an unprecedented 1,500-percent increase in value of his work reveal the impact the artist had on the art scene before his untimely drug-related death in 1988 at age 27.

Despite Basquiat’s Big Apple roots, the artist’s first institutional solo show was actually in Scotland, at Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket gallery in 1984. Yet no public institution in the UK owns work by the artist, and there hasn’t been a major exhibition of his paintings since 1996, when the Serpentine Galleries showed a selection of just two dozen canvases. This dearth of Basquiat in Britain has only spurred interest, however. Nairne says the public response to the show has been overwhelming, with the roughly 2,000 visitors daily and tickets selling out almost every day. “It’s incredibly affirming because not only has this show been a real labor of love to get here,” she says, “it’s massively important—this group of works will probably not be all in the same place again in our lifetime.”

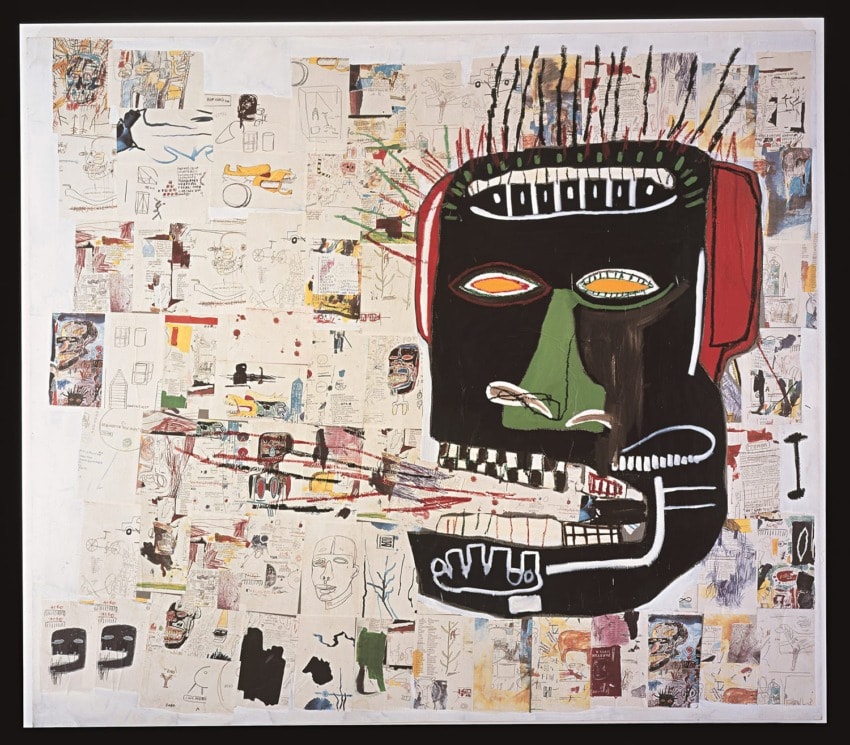

The strength of the Barbican’s show, above all else, is how firmly it places the artist in a rich tradition of distinctly American art history. The lower level of the exhibition moves away from a chronological account of the artist’s life and instead delves into recurring themes and historical referents in his work, such as his interest in folk artists like Bill Traylor to his racially charged compositions devoted to classic Jazz figures such as Charlie Parker. Additionally, it explores his unique ability to blend high and low culture, as evidenced in his ability to cite cartoons as easily as semiotics.

Basquiat was not just an uncannily accomplished artist and gregarious social figure, but an intellectual giant. “I know it sounds a bit trite, but I genuinely find and learn new things in the work all the time,” Nairne says. “The more you see of his work, the more apparent it is that he wasn’t just ferociously intelligent, he was also sharply funny.”

The exhibition closes with a rare interview with the artist from 1985. Conducted by his friends Becky Johnston and Tamara Davis, the film footage is surprisingly candid, and Basquiat’s wit comes to the fore. In it, they note that many reviews of his work focus on his persona rather than his art, to the artist’s chagrin. And while he certainly did cultivate a persona, one that “Boom for Real” begins by chronicling his myth, it ends just as he would have wanted: with his art and the man behind it, in his own words.

“Basquiat: Boom for Real” is on view through January 28, 2018 at the Barbican Art Gallery, Level 3 of the Barbican Centre, Silk Street, London.