Why Contemporary African Art is in Hot Demand

With a slew of major exhibitions, auctions, and fairs, the African art scene is on the rise

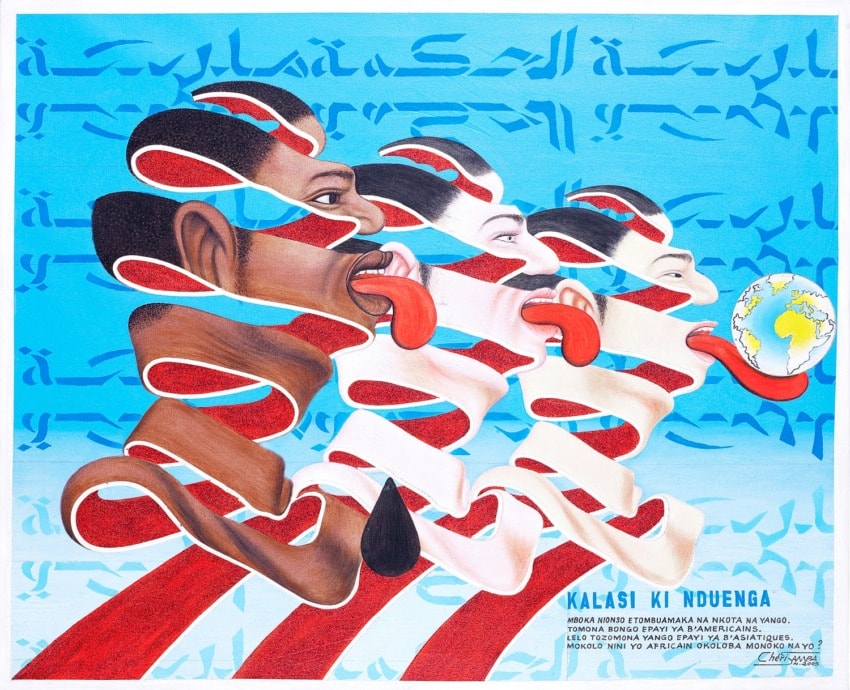

Republic of Congo. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Pascal Polar

African art has been ready for its close-up for a long time, and the international market is quickly catching up. In May, Sotheby’s London held an inaugural sale for its Modern and Contemporary African Art department, with 115 works selling for a total of £2.8 million ($3.6 million). The event ushered in record-setting prices for such artists as Ouattara Watts, Pascale Marthine Tayou, and António Ole, and the final bid for the celebrated British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare MBE’s sculptural installation Crash Willy (2009) beat expectations, commanding a whopping £224,750 ($297,000) against an estimate of £120,000–£180,000 ($159,000–$238,000).

While the market was once driven by local collectors and strongly affected by fluctuating oil prices and exchange rates, it has now expanded to include collectors worldwide, says Hannah O’Leary, the director of Modern & Contemporary African Art sales at Sotheby’s: “We had a lot of buyers in Africa, of course, but we also had registrations from nearly 30 countries.”

Collectors are also discovering works through fairs like 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, which holds events in London and New York and is expanding next year to Marrakech. The organization’s mission goes beyond bringing more attention to the art, says curator Koyo Kouoh, who organizes FORUM, the education program for 1:54. The goal is to use the expanding market to “feed and foster knowledge and appreciation in Africa itself,” she says.

Museums have always played a major role in drawing attention to African artists. In 1996 the curator and art critic Okwui Enwezor organized “In/Sight,” a seminal show of African photography at the Guggenheim Museum, but

it has taken until the last few years for momentum to pick up. Recent shows have been more political or had an advocacy bent. In the Tate Modern’s 2012 exhibition “Meschac Gaba: Museum of Contemporary African Art,” the Benin artist critiqued the ways African artists are often overlooked, and in 2015 the Brooklyn Museum’s staging of “Zanele Muholi: Isibonelo/Evidence” introduced its audience to contemporary issues surrounding LGBTQ rights in South Africa. In the fall the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa will open in Cape Town, South Africa, under the directorship of Mark Coetzee, making it the continent’s first major institution solely dedicated to contemporary art.

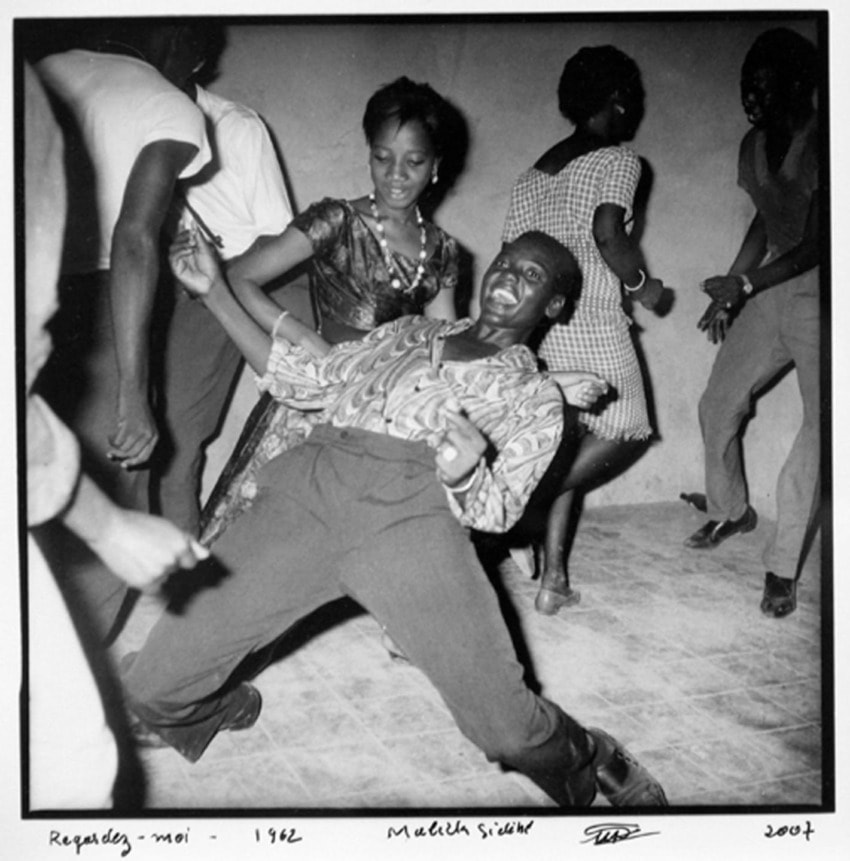

For dealers who have been longtime supporters of African art, the attention is overdue. “Claude Simard, my late partner in the gallery, and I loved to bring new things into the arena, so to speak, because we thought they were so good and needed to be seen,” says gallerist Jack Shainman, whose roster includes the late Malian photographer Malick Sidibé and the Ghanaian sculptor El Anatsui, who was awarded the prestigious Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement at the 56th Venice Biennale for his assemblage that evokes Africa’s modernity. At the recent Sotheby’s sale, Anatsui’s Earth Developing More Roots sold for a reported £728,750 ($963,000), but Shainman says creating a market for African artists has “been a long and arduous process” because “there’s no exact recipe.”

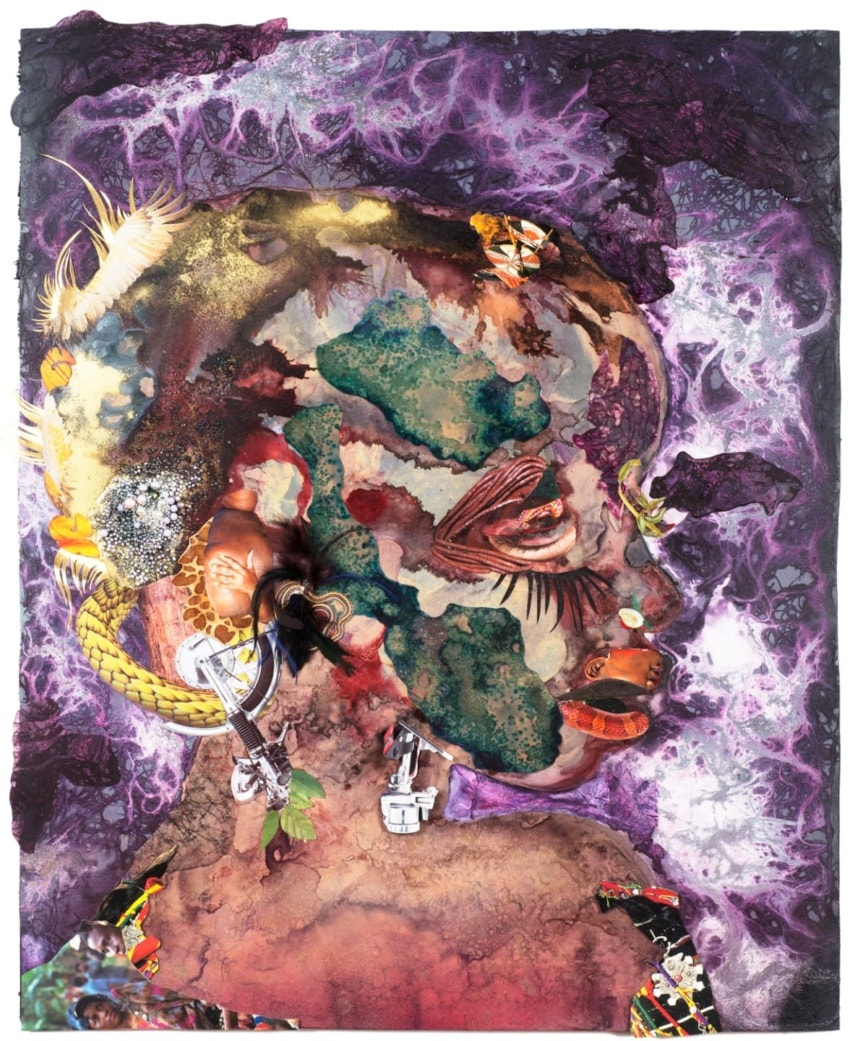

Like museums, galleries are showing the art in a larger sociopolitical context. Goodman Gallery in South Africa, which represents heavyweights like William Kentridge, Sue Williamson, Kudzanai Chiurai, and Tracey Rose, also has a curatorial arm, Goodman Projects. The 2016 Projects series In Context presented “Africans in America” and paired black American and African artists together as a way to speak to the histories between Africa and America, transcending the commercial. Exhibitions like this “generate new ways of looking, reading, and thinking—not only collecting,” says Liza Essers, Goodman Gallery’s director.

Taking a broader view is paying off: In 2015 Shainman organized the show “El Anatsui: Five Decades” at his 20,000-square-foot exhibition space in upstate New York, and “on the opening Saturday in the middle of the summer, two hours north of the city, we got five or six hundred people to come see the show—he’s a rock star.”

The contemporary African art market is still very young and evolving, but as galleries, fairs, and museums work to build context, Sotheby’s O’Leary notes, “there are real opportunities in this market to get in and make some serious purchases as it develops. It’s a wonderful time to be collecting.”