How Ai Weiwei Got His Big Los Angeles Moment

With new exhibitions across the city, the artist is making a mark on the California art scene with his politically charged work

There were huge crates everywhere in the UTA Artist Space in Beverly Hills in the days before the October 4 opening of Ai Weiwei’s show “Cao / Humanity.” Only one piece was unpacked: a nearly 15-foot tall tree trunk. Except, as you drew closer, it became clear that the tree trunk was not really a tree trunk but a representation made from iron.

Iron Tree Trunk (2015) comes from one of Ai Weiwei’s more contemplative series. Inspired by markets in northeastern China, where tree trunks and branches are sold for decorative purposes, the iron trunks (he’s been making them since 2009) are a sort of visual sonnet about how trees play a role in our lives and ideas of reproduction and artificiality in art production.

There are other works by the artist in other parts of Los Angeles as well: five major works at the Marciano Art Foundation for “Life Cycle,” the first L.A. institutional survey of the Berlin-exiled, Beijing-born artist, which opened on September 28. And hundreds of stools nearly fill Jeffrey Deitch’s new, 15,000-square-foot art space in Hollywood, where Ai will also show paintings of the Chinese zodiac in the gallery’s debut show, “Zodiac.”

It’s practically an Ai-Fest for Angelenos.

“The subject is ‘humanity’—the overarching subject that connects with Human Flow,” says Larry Warsh, who edited the Ai’s recent Humanity (Princeton University Press), a book of aphorisms and contemplations about what he’s seen while documenting refugees during the past few years, and is one of Ai’s most dedicated collectors.

“Right now, the main event of Ai Weiwei in L.A. is manifold,” continues Warsh. “It establishes him there. It’s a full 360 degrees of Weiwei. You’re seeing introductions of new work—the zodiacs at Jeffrey Deitch’s—and a big talk with Michael Govan at LACMA, and the weight of the show at the [Marciano].”

The weight of these shows lies in the inherent political motivations that Ai brings with him. The tree series at UTA Artist Space may be meditative, but there is an inherent connection to politics in all of Ai’s work—trees are part of our threatened environment, after all.

His work is often more directly political. Also on view at UTA Artist Space will be Humanity (2018), a new piece where the audience will read selections from the book on camera, which will be turned into a video work.

“It’s a viral component in terms of connectivity and exchanges from the public on the issues of immigration and what’s going on with refugees,” says Warsh. “He’s a truly global thinker.”

Jeremy Zimmer, the CEO of UTA—which will also be showing several sculptures and a floor work entitled Cao (2014), which consists of 727 tufts of grass made from marble—echoes that sentiment in an email interview.

“Ai Weiwei has long had an international mind-set,” Zimmer says. “He grew up in China but spent the early years of his career in New York. The work has always shown how political struggle, climate change, and human rights disregard geographic and political borders. The current political climate affects all of humanity so we need to come together to find a solution rather than focus on our differences.”

UTA’s artist representation division has long had a relationship with Ai, notably helping him develop Human Flow, Ai’s unforgettable and heart-wrenching documentary about the global refugee crisis from 2017. During a meeting with UTA—a talent agency known for representing actors like Angelina Jolie, Chris Pratt, and Gwyneth Paltrow but has lately entered the fine art world—Ai offered to design its new Beverly Hills gallery, working with UTA’s late artist representative Josh Roth, who died just before the show opened.

“When Josh Roth showed Ai the space, Ai thought it resembled his studio in Beijing and was excited at the opportunity to help design the building,” says Zimmer. “His vision was to utilize both the interior and exterior space and to remove some of the walls and expose the ceiling to make it more expansive. The brightness of the gallery is very much due to Ai’s design.”

At the nearby Marciano Art Foundation, Ai’s work has similarly transformed the space’s first-floor Theater Gallery. Two of his most memorable pieces, Sunflower Seeds (49 tons of porcelain sunflower seeds made by porcelain workers in China’s Jiangxi Province in 2010) and Spouts (2015), are laid on the floor, giving the impression of crops or reflecting pools.

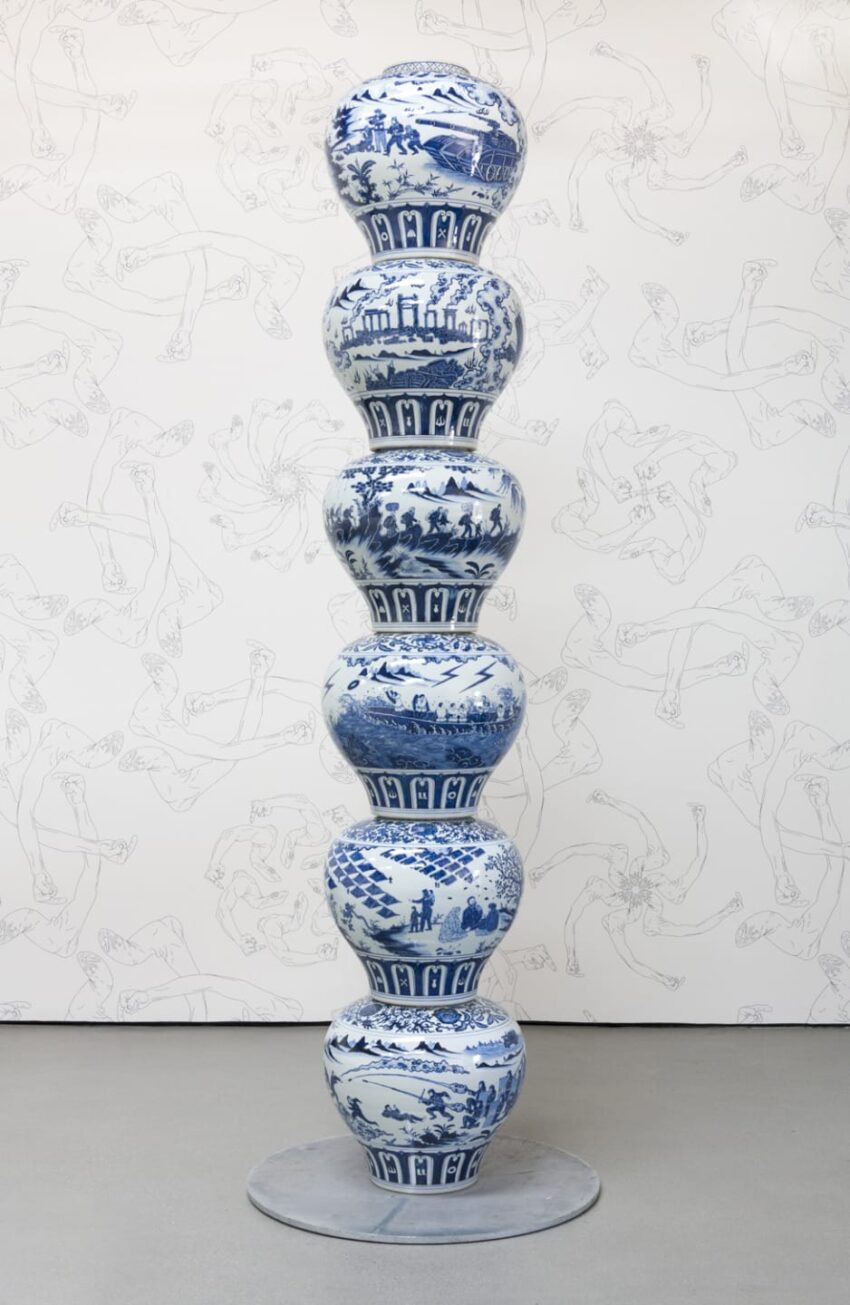

Also on view are three major works: Shanhaijing (2015), which depict creatures from the canonical fourth-century Chinese mythological text; Windows (2015), bamboo wall hangings that act as a sort of autobiographical work, including representations of the surveillance cameras, the middle finger that made him famous so long ago, and other highlights from his life.

In the middle of the MAF’s gallery is a new work, Life Cycle (2018), a bamboo representation of an inflatable boat like the ones used by refugees to cross the Mediterranean Sea.

According to a representative at MAF, Life Cycle was the last work Ai got out of his studio in Beijing—where he’d been under political house arrest for four years—before leaving China to move to Berlin. Ai also grew up a refugee, the son of a dissident poet during a time when China sent intellectuals to “reeducation” camps.

Recommended: Incredible Ettore Sottsass–Designed House in Hawaii Lists for $9.8 Million

“Many of us are so far removed from the unthinkable horrors faced by refugees and those living without basic human, social, and political rights,” says Jamie G. Manné, deputy director of Marciano Art Foundation, in an email interview. “It’s difficult to genuinely understand their plight, which is all the more reason why it’s crucial that an artist like Ai, who has lived through and understands the experience of the refugee, is able to communicate these real human experiences through his work.”

Life Cycle and Humanity present particularly optimistic commentary on the crisis.

“The personal experience becomes a political one—one that can be shared with others, in this case, through sculptural installation,” Manné says.

This is Ai’s big Los Angeles moment, and in some ways, his work was built for the city—large scale and impressive and not quiet, there’s a sort of Hollywood quality to it but with a message. It’s not the first time Angelenos have seen Ai’s work—“Zodiac Project,” a re-creation of 18th-century animals head sculptures that once stood at the Old Summer Palace in Beijing before being looted by Anglo-French troops in the Second Opium War in 1860, came to LACMA in 2011.

Over 120,000 people came to the museum for that exhibition. But this series of exhibitions comes at a different time, when refugees are forced to pass between global borders for reasons of war or climate or otherwise at exceedingly growing rates.

“It’s our hope that by sharing these ideas with MAF’s visitors, they will come away with a deeper understanding of these continual human struggles,” Manné says. “And that they might feel inspired to do something to help solve the problems related to the displacement and exile of human beings.”