Henri Matisse’s Daughter Marguerite Inspires New Exhibition in Paris

The galleries of the Musée d’Art Moderne are filled with works exploring the close relationship of the French artist and his eldest child

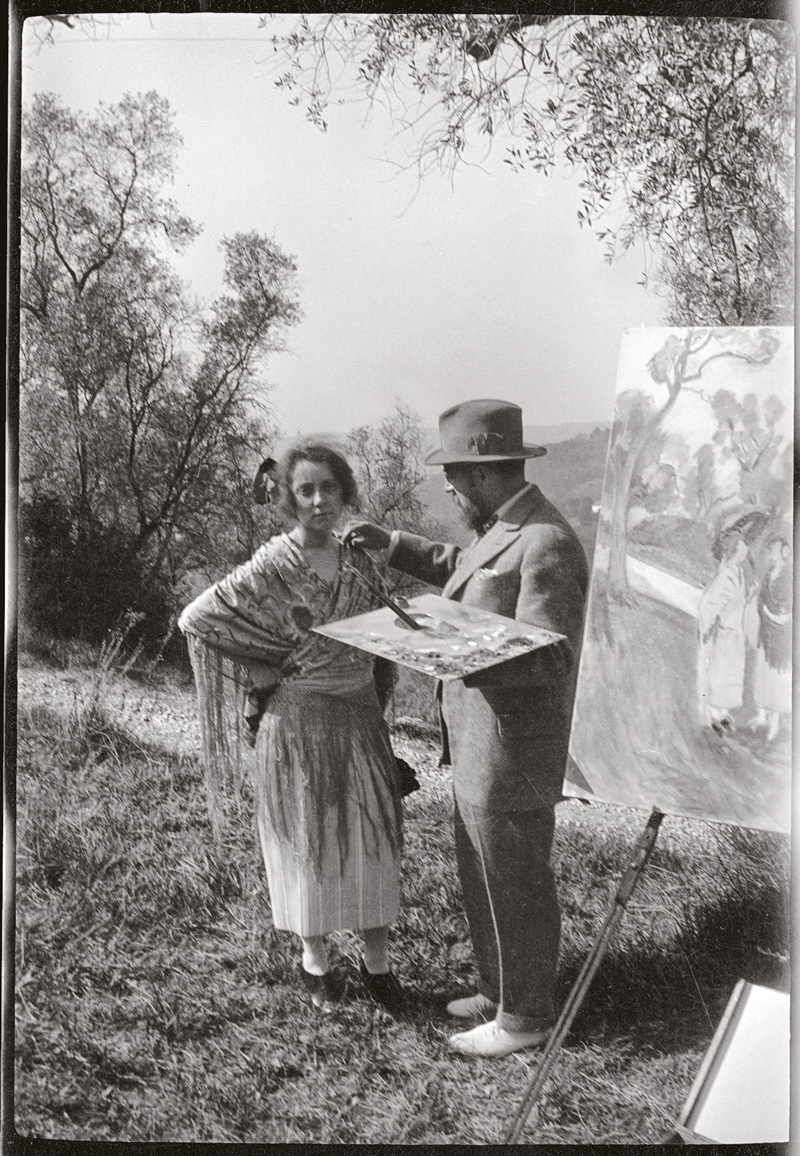

Séance de pose à Nice pour le tableau (1921). Photo: Archives Henri Matisse

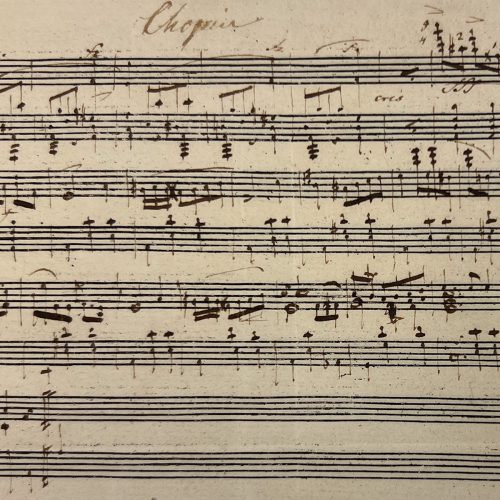

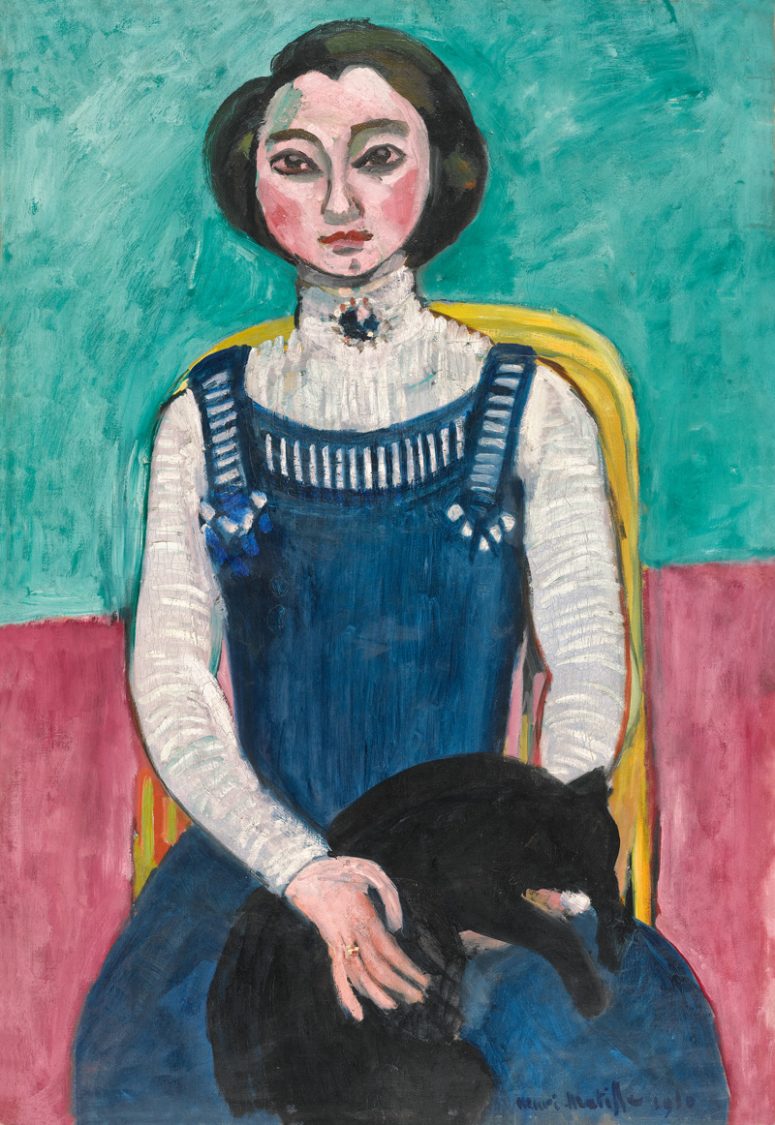

In one of Henri Matisse’s most famous paintings, a young girl in a blue pinafore sits on a chair with a cat on her lap. Dark-haired and round-eyed, she stares into space, her high collared blouse rising to her chin. This is Marguerite with a black cat, made in 1910, and the sitter is Matisse’s first child.

Marguerite was born in 1894, in a Paris clinic, to a 21-year-old woman called Caroline Jobland. Jobland had known Matisse for two years, but the couple didn’t marry. When Matisse met Amelie Parayre a few years later, Marguerite became absorbed into this new family, and as a beautiful exhibition in Paris now shows, his first-born was to appear in his paintings for the next fifty years. It is a whole new way to look at Matisse’s artistic career and his tightly wound relationship with his daughter.

Henri Matisse, Tête de fillette (Marguerite) (1906). Photo: © François Fernandez

Henri Matisse, Marguerite au chat noir (1910). Photo: © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist.GrandPalaisRmn /Georges Meguerditchian

The galleries of the Musée d’Art Moderne are filled with familiar paintings, and the wonderful drawings that Matisse made throughout his life. “They are so fragile,” says co-curator Charlotte Barat-Mabille of the latter. “And we have a lot from private collections, so this exhibition will not travel. It will only be here in Paris.”

Among the best known works is the 1906 Interior with Girl Reading, with its splashy fauvist background and trinity of domestic objects on a cloth on the table. But here you find yourself focusing for the first time on the girl. It’s Marguerite, of course. By now, she has suffered from a horrendous bout of diphtheria. By 1909, she has had a second tracheotomy, leaving her throat scarred. The high collars that conceal it will last until her 20s, when the scar is removed.

Henri Matisse, Marguerite (1906-1907). Photo: Grand palais RMN (musée national Picasso-Paris) / René-Gabriel Ojeda

“Marguerite is more than just a model for her father,” says Charlotte Barat-Mabille. “He began to listen closely to her opinion, and she’s very frank with him.” In a letter dated 1920, she tells him to come back to Paris. “Nice is not working for you,” she declares. As he becomes better known, she becomes his ambassador, or gate-keeper, representing her father in the face of voracious dealers and collectors.

The exhibition takes us deftly through this young woman’s extraordinary life. She’s quite the fashionista, and by her early 20s is wearing the latest designs by couturiers like Paul Poiret. You see her outfits in totally period black and white photographs from the time, and then their recreation in paintings by her father. A particularly stunning work, with a sense of Manet about it, shows Marguerite as the epitome of style in a navy velvet hat. (Portrait of Marguerite, 1918).

Henri Matisse, Amélie Matisse et Marguerite Matisse à Collioure (1907). Photo: Archives Henri Matisse

The dynamic that clearly existed between the pair is palpable. Matisse’s one leap into cubism—the staccato White and Pink Head from 1914—started, according to documentation seen by the curators, as a conventional portrait, before the artist asks Marguerite: “Do you feel up to trying something else?” The portrait that emerges suggest that Marguerite is part of the adventure, more collaborator than muse.

But she had her own life. In 1923, she married a writer and critic called Georges Duthuit in the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. Man Ray took the wedding photos. She also tried her hand at painting over a couple of decades. There is touching portrait of her stepmother in the garden, using her father’s colors: salmon pink, marine blue, forest green. She dabbled in dressmaking, too: a pink organza dress she made in 1935 suggests she was a talented seamstress.

Henri Matisse, Marguerite endormie 1920. Photo: Collection particulière / © Martin Parsekian

In the second World War, she joined the Resistance, and was caught in the northern town of Rennes by the Gestapo. Though she was put on the last train to the death camps in 1944, it somehow got derailed at the French/German border and she survived.

The last two drawings that Henri made of her are here: exquisite charcoal portraits of his beloved daughter made upon her return in 1945. He died nine years later. They are the perfect coda to an exhibition that puts a relationship front and center.

“Matisse and Marguerite: Through Her Father’s Eyes” is on view at Musee d’Art Moderne de Paris through August 24, 2025.