An Art Lover’s Guide to Edinburgh

The world-renowned Edinburgh International Festival brings a slew of shows and events to the buzzy Scottish art scene

August in Edinburgh is all about festivals. The world-renowned Edinburgh International Festival has been bringing dance, opera, music and theatre to the city since 1947, with the offshoot Festival Fringe swiftly springing up in its wake. Today, they encompass thousands of shows and events, with yet further festivals– from the Edinburgh International Book Festival to the Edinburgh Art Festival, launched in 2004 and dedicated to visual art—adding to the busy, buzzing scene.

“Underneath the umbrella of all the festivals we are the baby, but that does not mean that we are small,” says Edinburgh Art Festival director Kim McAleese. Encompassing 55 projects and exhibitions across 35 venues, and running until August 27, the multi-disciplinary programme ranges from in-residence events by Beirut-based cultural feminist organization Haven for Artists, to a showcase of emerging artists in the gothic Trinity Apse chapel, a sublime space down one of Edinburgh’s many charmingly cobbled alleyways.

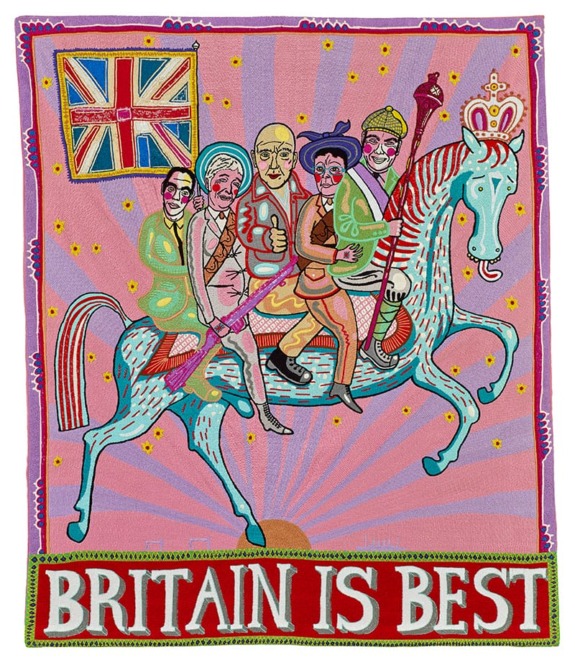

At the core of both the festival and the city’s art scene generally are a number of major institutions. The National Galleries of Scotland is spread across several venues: from the National’s neoclassical pile currently being headlined by “Grayson Perry: Smash Hits” (till November 12), a retrospective of the crossing-dressing British artist that spans monumental tapestries and his best-known ceramics pots—to Modern One, a space fronted with an undulating “landform” by artist and garden designer Charles Jencks, where the main event is “Create Dangerously”—a show from Barbadian-Scottish artist Alberta Whittle, who represented Scotland at the Venice Biennale in 2022. Across film, digital collage, painting and sculpture, Whittle’s practice is an impassioned resistance to racism.

Scottish women artists are being highlighted elsewhere. At The Scottish Gallery’s Georgian townhouse space, “Wonder Women” (till August 26) includes the work of Elizabeth Blackadder (1913-2021), who is the first woman to be elected to both the Royal Scottish Academy and the Royal Academy. Her boldly colored paintings feel strikingly contemporary. At Dovecot Studios, “Scottish Women Artists: 250 years of Challenging Perception” (till January 6 2024) is an eye-opener, highlighting often overlooked artists such as Bessie MacNicol (1869-1904), a member of the Glasgow Girls group of artists, whose portraits paintings were much admired during her lifetime, alongside contemporary creatives including Glasgow-based Zimbabwean-Scottish artist Sekai Machache, who will represent Zimbabwe at the Venice Biennale in 2024.

Machache’s tapestry work “Lively Blue” was commissioned by Dovecot Studios, and at the heart of this former Victorian swimming pool—the first public baths in Edinburgh, built in 1885—is a bustling tapestry workshop. The original top-floor viewing balcony now overlooks several looms, where a team of artisans weavers translate the work of artists—past and present; from Frank Stella to Chris Ofili—into textile form. It’s a must-visit at any time of year.

“Edinburgh is perhaps more known as a financial hub, but it does want to be a creative city,” says Dovecot director Celia Joicey. But while brightly colored posters and flyers for theatre or comedy shows dominate the city centre in August, much of the city’s rich contemporary art scene is found further from the beaten track.

Talbot Rice Gallery, for instance, is tucked along corridors and up staircases inside the University of Edinburgh, taking over a grand 19th-century former natural history museum with a punchy programme that currently includes immersive film installation The Tower by Irish artist Jesse Jones (till September 30)—a spellbinding evocation of deep feminism and ancient mysticism.

Another vibrant public space is Fruitmarket: the former market building perched above the city’s main train station, which from the outside looks like a buzzy hipster café, and is a good spot to stop for coffee and cake (or a glass of crisp Picpoul de Pinet), but also has a trio of gallery spaces. The recently added warehouse space—formerly a neighbouring nightclub—will host a performance by exciting British artist Florence Peake in October, combining exuberantly painted canvases with a troupe of dancers.

“The visual arts are slightly off people’s radar in Edinburgh; people come for theatre or comedy, but the great thing about the festival is that it brings people through our door without us even trying,” says Ben Harman, director of Stills—a centre for photography in Edinburgh’s Old Town, whose excellent exhibition of Prague-born, UK-based photographer Markéta Luskačová runs till October 7.

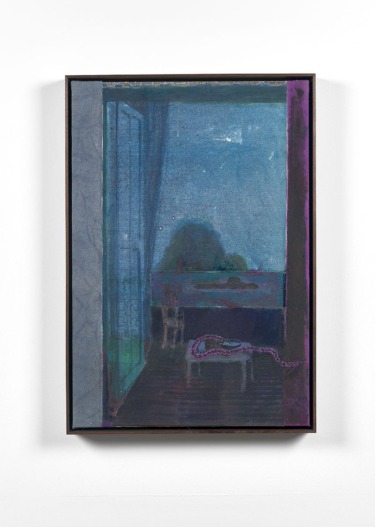

Any art tour of the city should also include Ingleby Gallery—a beautiful 19th-century building once used as place of worship by a small Scottish religious sect known as the Glasites, now hosting Scottish artist Andrew Cranston’s quietly dazzling narrative paintings (till September 16)—and Arusha. The latter’s roster of artists includes up-and-coming London-based painter Georg Wilson and ceramicist Claire Partington, whose intriguing fairy-tale-made-modern figurines will be the subject of a solo show from September 29.

For an art gallery with a view, Collective in the hilltop City Observatory is hard to beat, located next to the city landmarks of the National Monument, inspired by the Parthenon in Athens, and Nelson Monument.

Away from the city centre— two miles to the north; take a tram or a taxi—is the Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop in Newhaven. Predominantly a space for artist studios and workshops, its smartly minimal, white and brick building (designed by Sutherland Hussey Harris Architects) is a welcome change of architectural pace from the dominant dark stone and gothic spires. A window gallery and audio installation in the building’s tower provide “an unexpected encounter with contemporary art”, says Dan Brown, curator for research. “They connect what we do in this building, which is quite opaque, with the public.” Events also take place in the courtyard space, flanked by the stylish glass-walled Milk café.

Further afield still, but really not to be missed, is Jupiter Artland, a sculpture garden and gallery space launched in the home of Robert and Nicky Wilson in 2009—30 minutes west of the city. A visit begins with another cosmically conceived Jencks landscape, and throughout the grounds are works by internationally renowned artists including Tracey Emin, Christian Boltanski, Anish Kapoor and Phyllida Barlow. There’s a swimming pool by Joana Vasconcelos and the café is covered in murals by Nicolas Party.

This summer, Jupiter Artland’s annual exhibition is by Lindsey Mendick—an artist based in the English seaside town of Margate, who works predominantly in clay. Titled, “SH*TFACED”, the show is a playful but poignant exploration of contemporary binge-drinking culture, which also draws upon Robert Louis Stevenson’s Victorian novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. In the ballroom, a dinner party of bust-like vases crawl with grotesque serpentine forms, while another space summons up a nightclub—a surreal scene both debauched and disconcerting. The final installation is a confessional video work that lays bare Mendick’s and her partner, Guy Oliver’s relationship with alcohol, in the intimate setting of a 17th-century circular dovecot.

On Saturday August 19, Jupiter Rising X Edinburgh Arts Festival Party, curated by Mendick and Glasgow queer collective Bonjour, takes place. The event is also a “reason for dancing”, adds McAleese. “Across the festival we will be discussing difficult and at times quite traumatic experiences, but creating moments of joy is important as well.”