A Rare Look at Tehran’s Forgotten Red-Light District on Show at the Tate

Iranian photojournalist Kaveh Golestan’s socially engaged series of prostitutes are given a permanent home at the museum

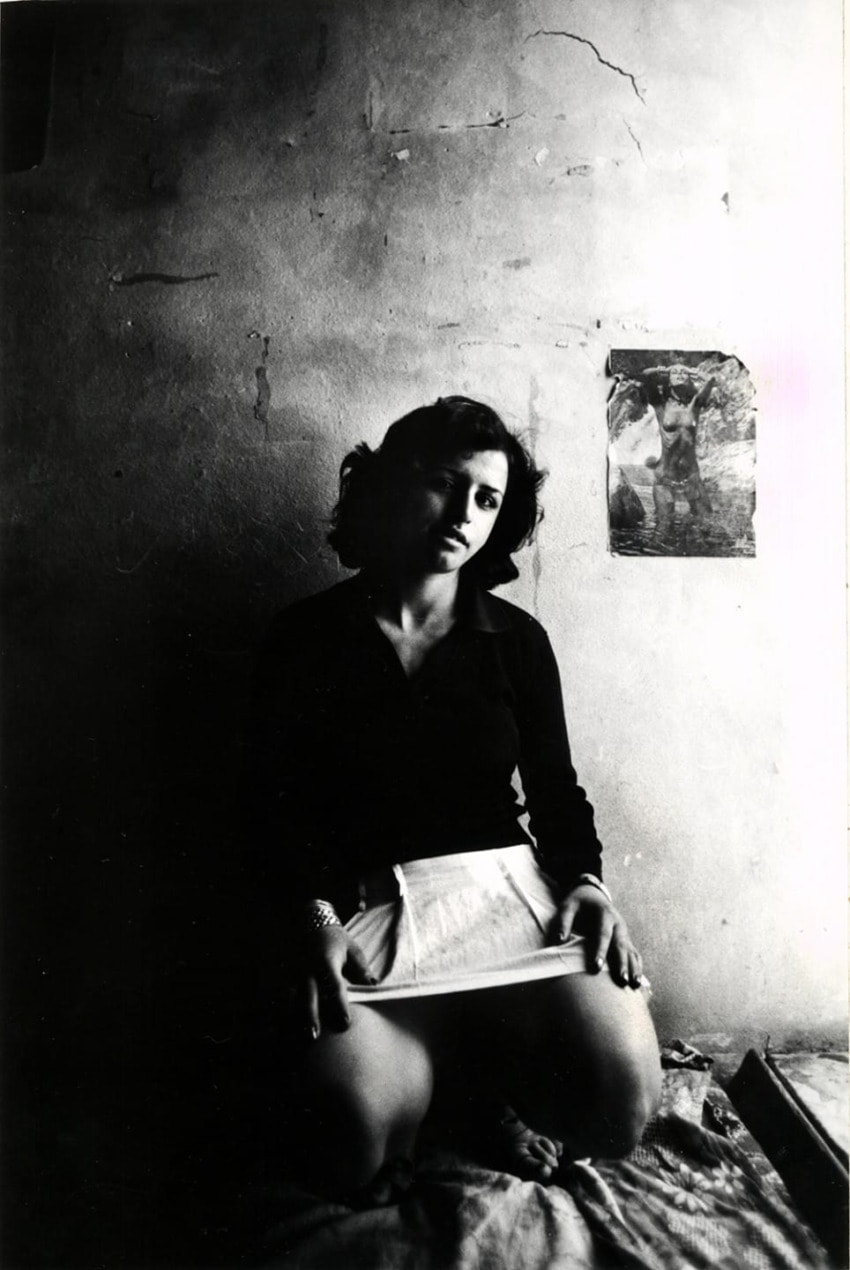

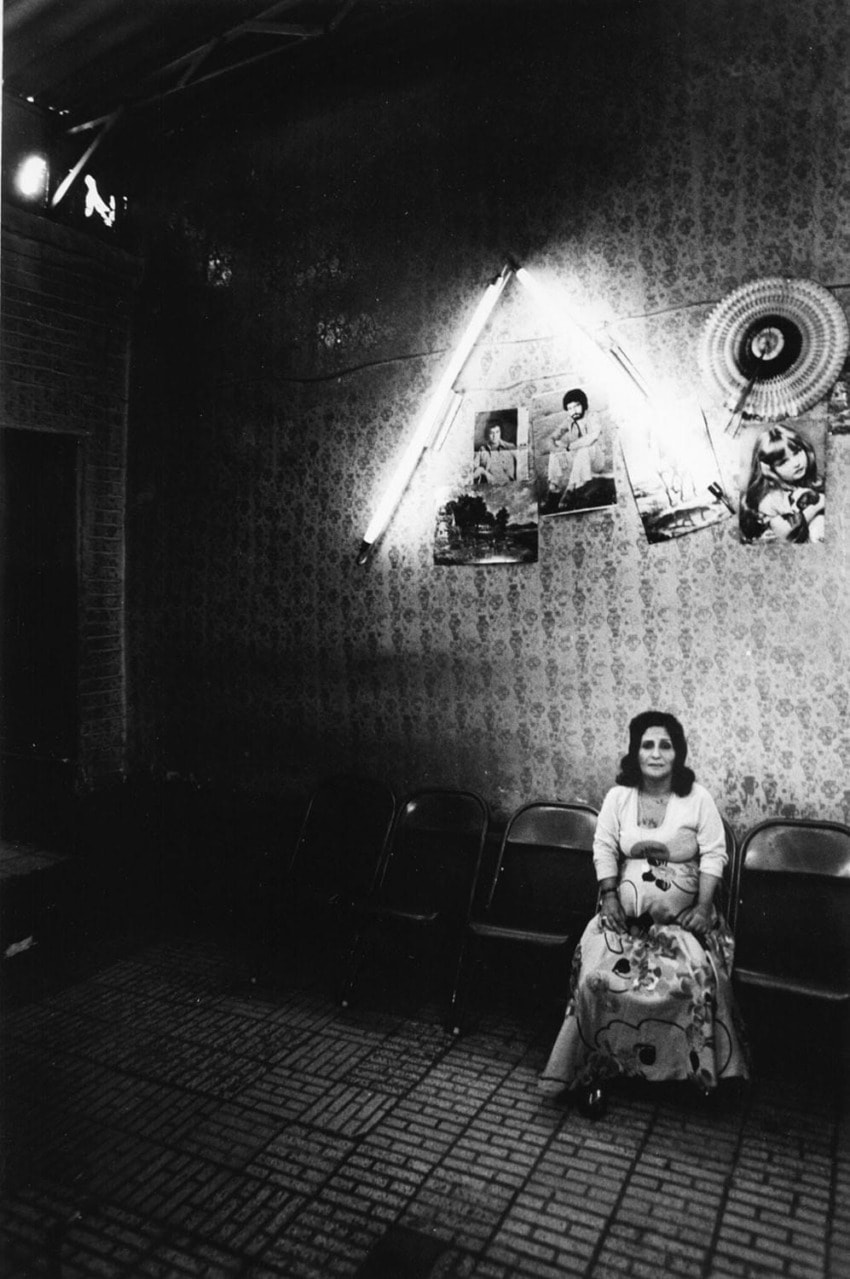

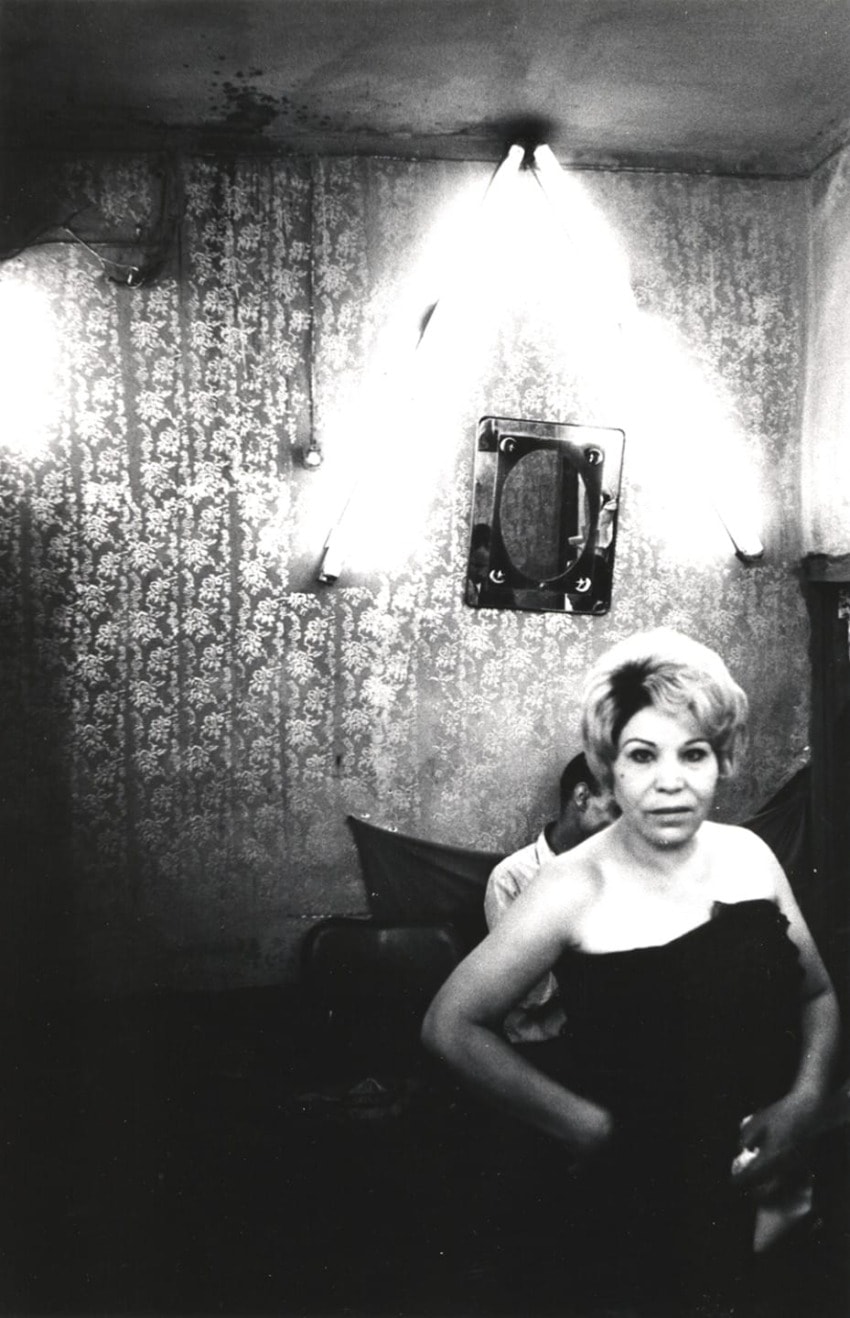

Taken between 1975 and 1977, Kaveh Golestan’s series of photographs documents sex workers from the former red light district, Shahr-e No, in Tehran, Iran, known as the Citadel. The late Golestan’s photographs portray the bleakness of the sex trade with cutting frankness as well as a society on the brink of revolution. Captured here is the candid beauty and sorrow of these women set against Tehran’s urban landscape. These haunting black-and-white images tell a tale that many still have yet to know.

The result of a deeply personal mission, Golestan entered the Citadel without an official permit. He wanted to publicly expose its interior in three consecutive photo essays in the Iranian daily newspaper Ayandegan in 1977. The 61 portraits that made up the final project were edited down from a larger pool of negatives. Over the years in which he photographed these women, he forged friendships with the residents—relationships that helped to create his work and endowed his photographs with empathetic understanding. “I want to show you images that will be like a slap in your face to shatter your security,” said Golestan. “You can look away, turn off, hide your identity . . . but you cannot stop the truth. No one can.” And indeed no one could. Nor could they stop what would happen just a few years later when the district was burned to the ground in a terrible fire set by religious militants aiming to purify the city before the return of Ayatollah Rullohah Khomeini to Iran. With the fire went the cabarets, the brothels, and the nightlife of this marginalization of Iranian society. In but a fragment of time, the Citadel was no more.

Decades later, in 2014, Golestan’s “Prostitute” series resurfaced in London-based curator Vali Mahlouji’s Archaeology of the Final Decade (AOTFD) project, a nonprofit curatorial and educational platform working to expose the work of artists who have been neglected due to historical circumstances. “The idea of cleansing from there [the Citadel] was such a cruel and inhumane response to the humane work that had being happening at the time to shift the view of marginalized people,” said Mahlouji of the fire. The photographs serve as the only memory of these women and the Citadel. Today, where the district used to be, there is a park.

“While we are excited about the photographs being displayed, the sociopolitical history that we have executed is very important,” says Mahlouji, “We have a very think-tank attitude to every object—they help us to better understand history.” While Golestan’s photographs were taken from 1975–1977, Mahlouji’s research on the subject matter of prostitution in Iran took him back to the 1920s as well as forward to the ’80s. “It revealed social attitudes regarding prostitution in general in Iran as well as women’s organisations that provided social work for the prostitutes,” he explains. “There was a very sophisticated movement taking place at the time, urging the government to pass laws in order to protect these women and their offspring. Women during the ’60s and ’70s in Iran were doing really progressive work—work that was leading toward a radical shift in thinking.”

The Tate’s recent acquisition of 20 vintage prints from Golestan’s Prostitute series took place after the images were displayed in Recreating the Citadel, a traveling exhibition curated by AOTFD, transporting the works to Foam (Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam), Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, MAXXI (Museo nazionale delle arti del XXI secolo), in Rome, and Photo London, at Somerset House. The Tate’s acquisition follows similar purchases of Golestan’s work by Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris and Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

“Kaveh is known as a photojournalist, but these exhibitions have taken him out of this position and into the art world,” emphasizes Mahlouji. And it is through art that the sociohistorical tale of these women and this district can now be remembered. The Tate Modern has now dedicated a room to Recreating the Citadel: Prostitute (1975–77) featuring Golestan’s work alongside research materials uncovered by AOTFD. The room marks the first time in the museum’s history that a gallery in its permanent collection has been dedicated to an Iranian artist. Golestan’s original intention was to reveal to the public the darker face of society; such photographs were intended to rupture urban complacency. They now have their rightful chance, and in so doing, also open the rest of the world up to a new postrevolutionary Iranian narrative.