Takashi Murakami Brings Cuteness and Catastrophe to Russia

The Japanese pop artist merges Eastern and Western traditions in a major survey at Moscow’s Garage Museum

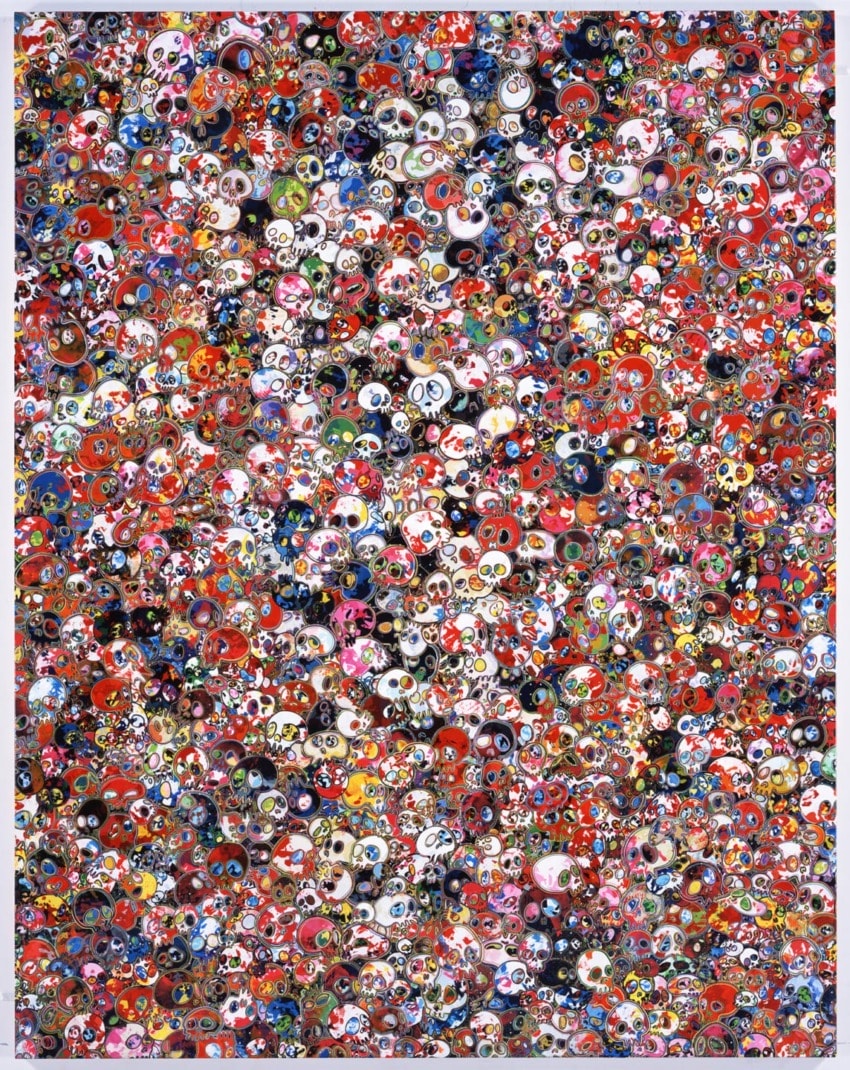

To kick off the opening of the first major survey of his art in Russia, the superstar Japanese artist Takashi Murakami flew down a slide built near the entrance of Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, where the show is on view through February 4. Titled “Takashi Murakami. Under the Radiation Falls,” the exhibition consists of five sections—“Geijutsu,” “The Little Boy and the Fat Man,” “Kawaii,” “Sutajito,” and “Asobi & Kazari”—and takes over the entire museum, showcasing how the artist has gingerly mixed Japan’s postwar pop phenomena of Manga and Anime into painting, sculpture, film, and merchandise.

“The curator of the exhibition wanted the show to represent a melting of a big wall between Japanese and Russian cultures,” the 55-year-old artist tells Galerie. He explained that the exhibition is partly inspired by “Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture,” the catalogue that accompanied the 2005 exhibition he curated at the Japan Society in New York. “The catalogue deals with Kawaii, the cute culture of [postwar] Japan” that helped establish what he calls a “superflat” culture where there is no distinction between high and low art. “It’s never just black or white, good or bad; it’s ambiguous.” He added, “My art explores this, and this is what the curator wanted to convey to the Russian audience.”

Right before the exhibition opened to the public, Galerie sat down with the artist, who is affectionately known as the “Andy Warhol of Japan,” to talk about his 25-year career merging Eastern and Western traditions.

The Japanese concept of Kawaii or “cuteness” runs throughout your work. When did you have this breakthrough?

“Up until the time I was making the Sea Breeze sculpture in the show (1992), I had been trying to reflect the twisted structure of [contemporary] political and social Japanese history. To do this, I was working with more industrial and artisanal materials. I was trying to have a very broad overview of the culture. But I realized that way of working was very difficult for Japanese people who were not educated in contemporary art, and for someone outside of Japan to grasp. So, I started exploring how I could make the art more digestible to these audiences, and I came across the postwar culture of Manga and cuteness.”

One of the things that comes out of your use of Kawaii, in works like Memories of a Passionate Life and Troll’s Umbrella, is the removal of the barriers between high and low culture. When you started to explore the cuteness of Kawaii, were you thinking about those barriers as limitations?

“When I was younger looking at contemporary art in Japan, [Kawaii] was on the same plane as all other culture. The existence of contemporary art in Japan is already flat, not high or low. When I first went to New York, ethnic art was becoming very trendy in the early 1994. David Hammons and Felix Gonzalez Torres were coming up. In that moment with my Japanese identity in the art capital of the world, I thought it would make sense to take my culture and put it into a contemporary context. I was thinking about the raw condition of Japanese culture. I wasn’t trying to melt the high and low into one, I was just trying to present my own background in contemporary art.”

How do the toys seen in Otaku toy sculpture and with your merchandise extend the language of your art?

“The Otaku poppy figure, I just blew it up and made it into a sculpture. As I said, there wasn’t this concept of high and low art in Japan’s postwar culture like in the West. There’s just flatness. For me, the flatness is my roots, so it’s very easy for me to do everything from merchandise to painting and sculpture within that flat plane. For 25 years, I’ve been making T-shirts, art, and toys. The time has changed and there’s a younger audience that has been exposed to my work over this period, and for them everything is art, there is no distinction.”

Is your embrace of social media, where we get to see you at work and at play, also about your ideas around flattening cultural hierarchies?

“I am not the type of artist who will shut myself off in order to be able to create something new. I actually branch out and pick up inspiration from all over the place. Often times, I am cooped up in my studio working and the only window to society I have is social media. Also, looking on Instagram, allow me to keep up with my friends. For example, sometimes, I’m like, “Oh, where’s Pharrell now?” And I see he’s in Paris at the Chanel fashion show. I get to know these things on social media.”

You have posted about listening to rappers, and artists like Migos, in the studio. What kind of influence has hip-hop had on you?

“Hip-hop is very direct and it has a message. It really touches me in certain ways. When I am listening to Migos, it’s really about word play. They create really interesting and funny words, which allows listeners to use their imaginations. That’s why I really like it.”

You have famously been nicknamed the “Andy Warhol of Japan.” Going beyond the father of Pop Art, who have been your influences?

“A big, big influence has been George Lucas. Immediately after releasing The Empire Strikes Back, he released the behind-the-scenes video showing how he made it. Our generation was shocked! Movies are a kind of fantasy, but his video was a how-to reality. He showed us the movie magic process. He helped to educate me to the fact it was a collaboration. So when I work on a big project I make it look like a George Lucas collaboration. For example, painting has a lot of processes, and in my studio, we divide them up. George Lucas was my big teacher.”

Speaking of collaboration, the museum has re-created your entire studio in the “Sutajito” section of the show. Why was it important to present a full-scale replica of your Tokyo studio at the Garage?

“The museum really wanted to emulate the feeling of what it means for me as an artist to work in Tokyo. When I came to my ‘Moscow studio,’ I said, ‘Oh my god! This looks like my real studio!’ It is a new experience for an audience in a museum. It allows them to be more deeply involved. It’s not just my painting and sculpture, but they also experience my studio.”

You have covered the traditional white museum walls with your iconic, multicolored flowers. Do you think your art in general has helped the museum experience to be more inviting?

“At first I was resistant to the idea and I wanted the conservative white walls. I’m essentially a painter so I like white walls! But now, being here in the museum and seeing the works installed, I see how new and fresh the works look.The curator really took the work and remixed it to present it in a new context.”

Looking back on your career as it plays out on the walls of the Garage Museum, it presents a picture of your life in some ways. How does your art tell your story and the story of postwar Japan?

“Artists all have something that really tugs at them. For me when my father worked for the army he used to tell me repeatedly as a child why Japan lost World War II. I feel like I was constructed from his stories and my art works through those themes.”

“Takashi Murakami. Under the Radiation Falls” runs through February 4, 2018, at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow.