10 Ways Napoleon Influenced the Past and Future of Art and Design

In honor of Ridley Scott’s new film starring Joaquin Phoenix, Galerie explores the French leader’s lasting aesthetic impact

When Napoleon Bonaparte died in 1821, he left behind a complex legacy: a brilliant military commander who cost his country millions of lives in battle; a leader who worked to emancipate Jewish and other religious minorities throughout the French empire, while reinstating slavery in some of its colonial territories; a visionary deployer of propaganda and branding who nonetheless is perhaps best remembered in the West for a (discredited, but Mariah Carey-referenced) stature complex and, of course, a giant hat. With Joaquin Phoenix chewing scenery as the emperor in a new Ridley Scott biopic, Galerie takes a look at ways Napoleon also changed the worlds of art, architecture, and culture.

1. The Art of Celebrating Yourself

Napoleon wasn’t the first to use the spoils of his kingdom to celebrate himself, but he did it at a grand scale that anticipated our current obsession with self-branding. He commissioned masterpieces like Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1801) which functioned as billboards for his military successes while intertwining his identity with that of his country. This diabolical boastfulness still powers politics today, while its mechanisms continue to be interrogated by artists like Kehinde Wiley, who recast David’s painting with a Black man in his Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps (2005).

2. The Empire Style

France was in thrall to the minimalist Directoire style until Napoleon came along and injected its neoclassicism with a flamboyant opulence. Architects Charles Percier and Pierre Fontaine led the charge to plumb Greek and Roman empires not for their geometric rigor but for their belief that ornamentation produces meanings—in this case, the splendor of empire. The movement’s faith in symmetry was of a piece with the Enlightenment, and its balancing of the austere with the ornamental feels particularly fresh today.

3. The Empire Waist

Speaking of empires, Napoleon’s first wife, Joséphine, was in large part responsible for his patronage of Percier and Fontaine. It was she, for example, who brought them to design the gardens for their Château de la Malmasion, which introduced a vast number of plant species to Europe alongside hundreds of varieties of roses. She also understood the political and personal power of fashion, helping to spark a revolution that led to slimmer, less restrictive clothing. The “empire” in the “empire waist,” after all, was hers.

4. Flower Power

Joséphine’s beloved flowers also climbed the walls of their home, thanks to the efforts of the Belgian botanist and painter (and Marie Antoniette’s court artist) Pierre-Joseph Redoute. His depictions and documentation of all her varietals in bloom helped plant the seed for the next two hundreds of botanical fascinations, from the stylized gardens of Scalamandre to the accessible bounties of Flavor Paper.

5. Walk Like an Egyptian

When Napoleon led his troops to invade Egypt in 1798, he returned with records of the architectural and aesthetic triumphs of the ancient country. France loved what they saw, and began building on earlier imaginings of Egypt to create a full Egyptian Revival style. Entire Parisian streets like Place du Caire were recast like ersatz little Cairos; mummies and crocodiles stalked popular culture and stage sets; and obelisks and pyramids rose everywhere from jewelry design to, after the colonies got whiff of it, the mall in Washington, D.C.

6. The Fabrics of Their Lives

During the revolution, French designers and patrons turned to muslin for their dresses, which was largely imported through England from India. To buttress domestic industry, Napoleon banned the fabric and mandated that all in his royal court wear garments of locally-made fabrics including silk and velvets—thus encoding those materials with glamor and prestige that continues to this day in luxury items like Hermés jacquard silk scarves.

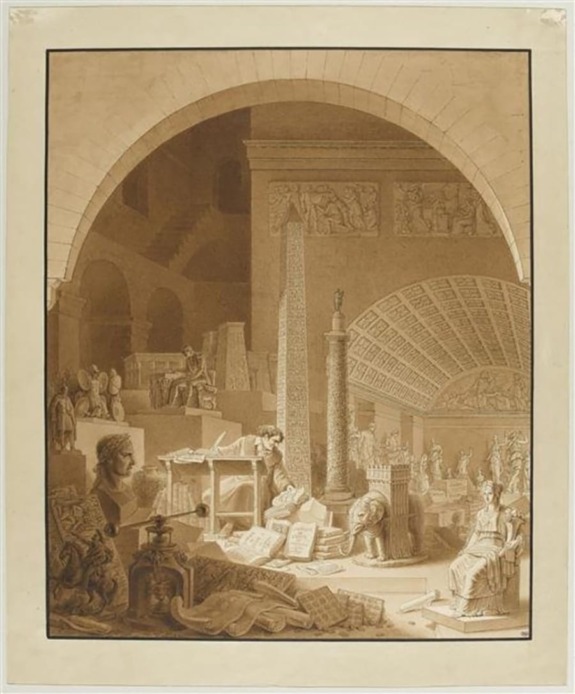

7. Museum Pieces

What we now know as the Louvre was originally a palace, then an apartment complex for artists. During the French revolution, it opened as a public museum to show off national achievements in the arts and sciences. Napoleon made the Muséum Central des Arts de la Républic over in his own image, renaming it the Musée Napoléon and installing the Egyptian Campaign veteran Dominique Vivant-Denon as its first director. The museum quickly became a repository for arts and other treasures looted during the Emperor’s military ventures throughout Europe and Africa—an ethically dubious institutional practice with legacies still being examined in our time, as calls for repatriating items in museum collections around the world gather strength.

8. Hats Off!

Of course, Napoleon’s greatest contribution to style might be his famed bicorn hat, a fairly standard piece of military headgear he revolutionized with a simple sideways twist. Instantly recognizable, the hat was eye-catching both on the battlefield and off, establishing the emperor as one of the few men in history whose millinery accomplishments were as notable as his military. The version he donned while meeting Alexander I of Russia was reportedly auctioned at Sotheby’s in Paris for some €1.2 million in 2021 (a lock of his hair went for €13,860). Meanwhile, statement hats have been taken up by everyone from the late Leigh Bowery to Pharrell and RuPaul with their mega-chapeau, to anyone brave enough to don a Philip Treacy confection.

9. Knowing My Fate Is to Be with You

The iconic Swedish geniuses ABBA found victory in Napoleon’s defeat, deploying his final battle at Waterloo for an anthem of the same name which won them Eurovision and launched their career in 1974. ABBA secured their place in architectural history in 2022, when they built their own hexagonal timber venue designed by STUFISH Entertainment Architects at London’s Olympic Park. The stadium hosts the band’s innovative “ABBAtars”, or virtual performers created using stop-motion technology—a brand-new kind of band to sing the beloved old hits, including, at the end of Act IV, their ode to the French emperor.

10. Socialized Artisans

Napoleon’s records on human rights and other ethics is, at best, mixed. But at a time when governments seem ever more interested in defunding the arts, we might look to him for inspiration. He founded the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry to support French manufacturing; the Garde-meuble Impérial to fund local furniture industries like Jacob Frères; and generally viewed artistic achievement and craftsmanship as intrinsic, not a threat to, his country’s success. That’s one campaign we might get behind.