Sean Scully’s Abstract Masterpieces Take Over a Mexico City Landmark

On the outskirts of Mexico City, a striking estate designed by Pritzker-prize winning architect Luis Barragán becomes an exhibition space

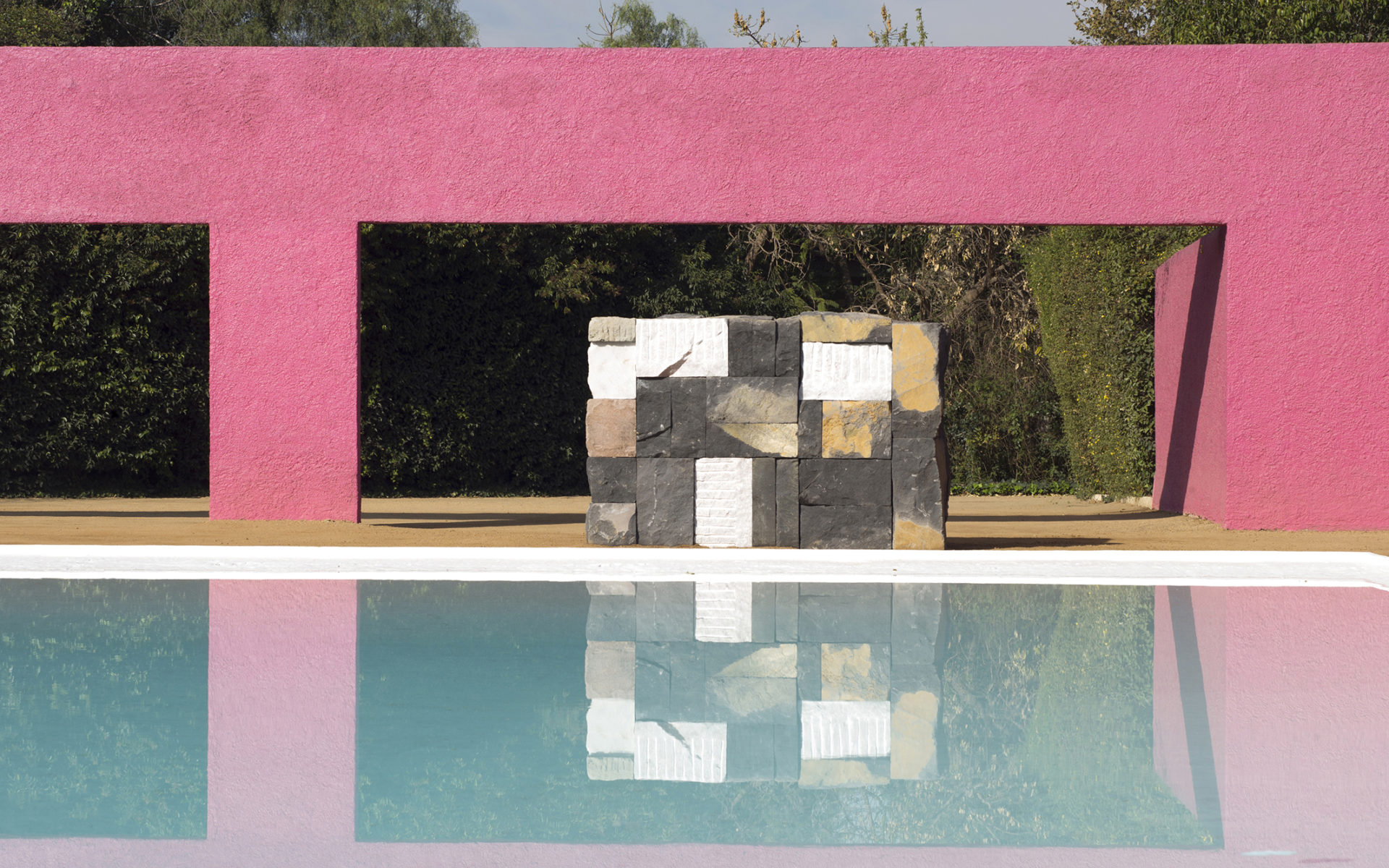

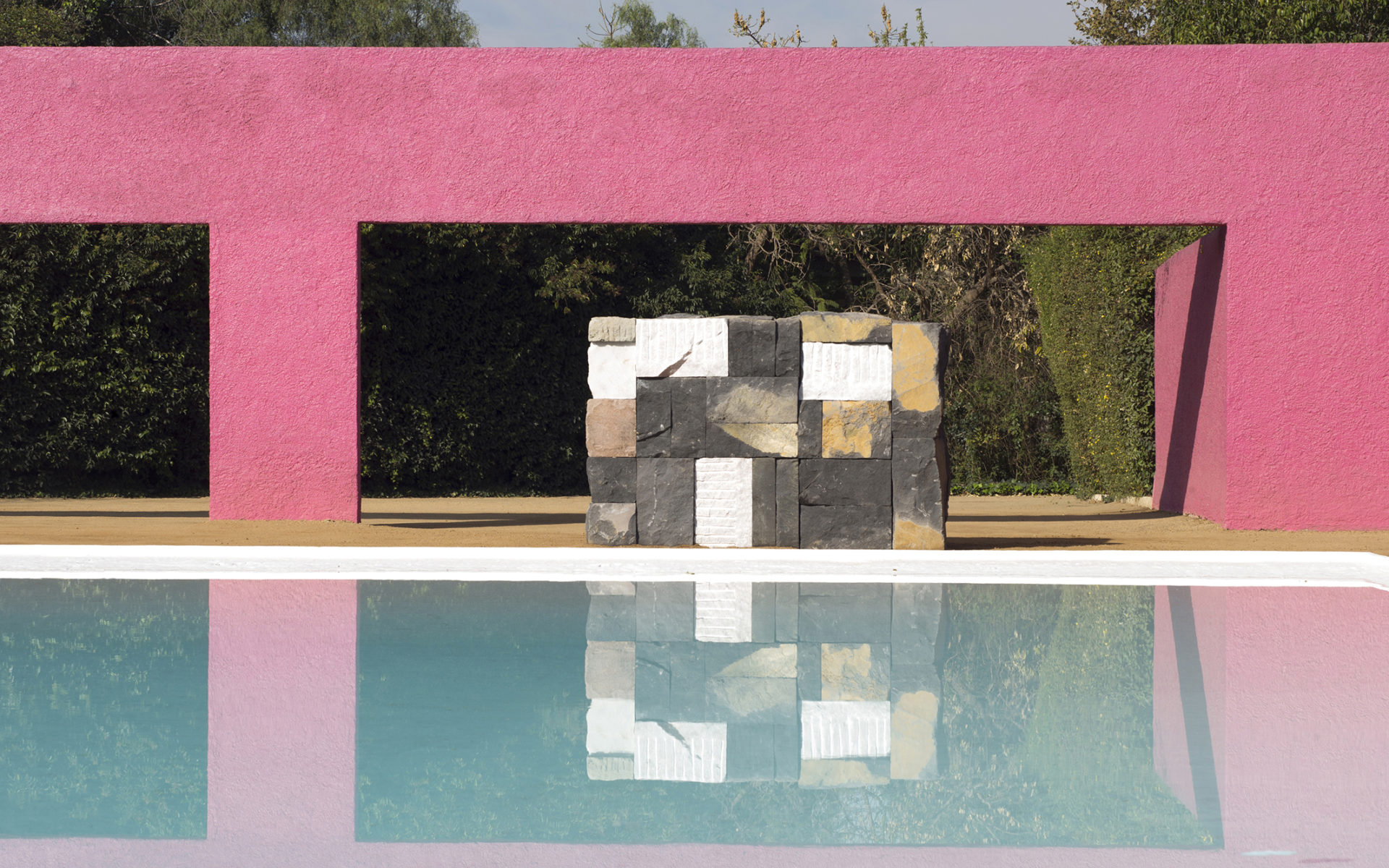

The candy hued Cuadra San Cristóbal compound in Mexico City—prime Instagram fodder—is now part of a more erudite program. Constructed between 1966–68 by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Luis Barragán, the structure may be best known for the solid bubblegum pink and purple walls that confine the dusty grounds out back, where horses used to roam.

Coinciding with the 15th edition of the Zona Maco art fair, a site-specific exhibition of 18 works by the Irish abstract artist Sean Scully are installed at the estate, allowing viewers to see the juxtaposition of art and architecture. While Cuadra San Cristóbal is as a mecca for architecture buffs as well as a popular location for photo shoots, this is the first time the landmark is being used as an exhibition space.

Mounted by London-based independent curator Oscar Humphries, the show (Scully’s first in Latin America) features 15 paintings and three sculptures, most spanning the past five years. Guests arriving at Cuadra San Cristóbal first encounter the whitewashed side of the residence, which was built for Swedish businessman Folke Egerström and his family, and has remained privately owned.

Brown Silver Tower, a striking cor-ten and stainless steel structure, rises between two walls whose color palettes mirror the sculpture’s silver- and rust-colored layers. It beckons toward the wide reflecting pool and open space beyond. Scully’s cor-ten steel Boxes of Air, installed in front of a monumental pink wall that demarcates the perimeter, are a series window-like open prisms that function like portals to the surroundings. To the right, a long, low building housing individual horse stables become gallery walls for Scully’s paintings.

The hay-floored stalls, however, offer a remarkably different aesthetic and olfactory experience than the white cube. The white walls feature dark brown stripes along the bottom and narrow metal bars jutting from the top. These horizontal and vertical forms enter an intriguing dialogue with Scully’s own trademark stripes. And at times, glimpses of the painting through the metal bars peep through. This is a perfect way to view the final work, Ghost, 2017, an indictment of the American criminal justice system. The painting resembles an American flag, with a gun at the top left; the weapon appears to have displaced the stars, which litter the painting’s corner. “It exaggerates the sense of jail,” Scully tells Galerie.

Scully has a long relationship with Mexico. In 1981, he began traveling across the country, taking photographs, picking up hitchhikers, and learning the language. “I had Montezuma’s revenge so many times that I became immune,” he divulges. Aside from that, he was particularly inspired by the way the light shifted throughout the day on the stones of pre-Columbian architecture. He synthesized those colors and forms in a new series of watercolors (his first since his student days), begun in the Mexican resort city of Zihuatanejo. He titled one of these 1984 works Wall of Light.

Over the next decade, his “Wall of Light” series grew to encompass a large body of paintings, aquatints (prints resembling watercolors), and pastels. Resembling overlaid bricks, his blocks of rough stripes evidenced his interest in architecture, ruin, and decay. In 2006, the Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted a major exhibition of these works. Many of the same elements are on view in the included series—Wall, Window, Robe, and Landline—at Cuadra San Cristóbal: rough brushstrokes, deftly mixed colors, and shadow-like gaps between stripes.

For the exhibition catalogue, Scully penned an essay about his photography, relationship with Mexico, and obsession with time and decay. “I’m a good writer and a good drinker,” he said. He admires the writings of artists such as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky, claiming it can “articulate a kind of spiritual aspect in art” that formalism-concerned critics often overlook.

“What makes Barragán interesting for people,” he says, “is it’s spiritually charged. People talk about the sense of silence around Barragán, the emotional content in it or the fact that it looks almost religious. It creates spaces that are almost mystic or mythic.” Decked out with Scully’s paintings and sculptures, Cuadra San Cristóbal becomes doubly so: a temple of color, texture, and feeling.