Looking Back at the Extraordinary Career of Sculptor Ruth Asawa

David Zwirner’s first exhibition of her work celebrates a lifelong dedication to experimenting with wire

“It’s amazing that Ruth Asawa was relatively unknown for as long as she had been,” says Jonathan Laib, a director at the David Zwirner gallery in New York. He explained that the looped-wire sculptures of this American artist, who died in 2013, had historically been mislabeled as craft because of her use of unconventional materials and techniques. In recent years, while working at Christie’s, Laib sold important Asawa works to such institutions as the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art, and earlier this year he moved with her estate to Zwirner, where her work could be shown in the context of major artists such as Josef Albers, Asawa’s influential teacher in the late 1940s at Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

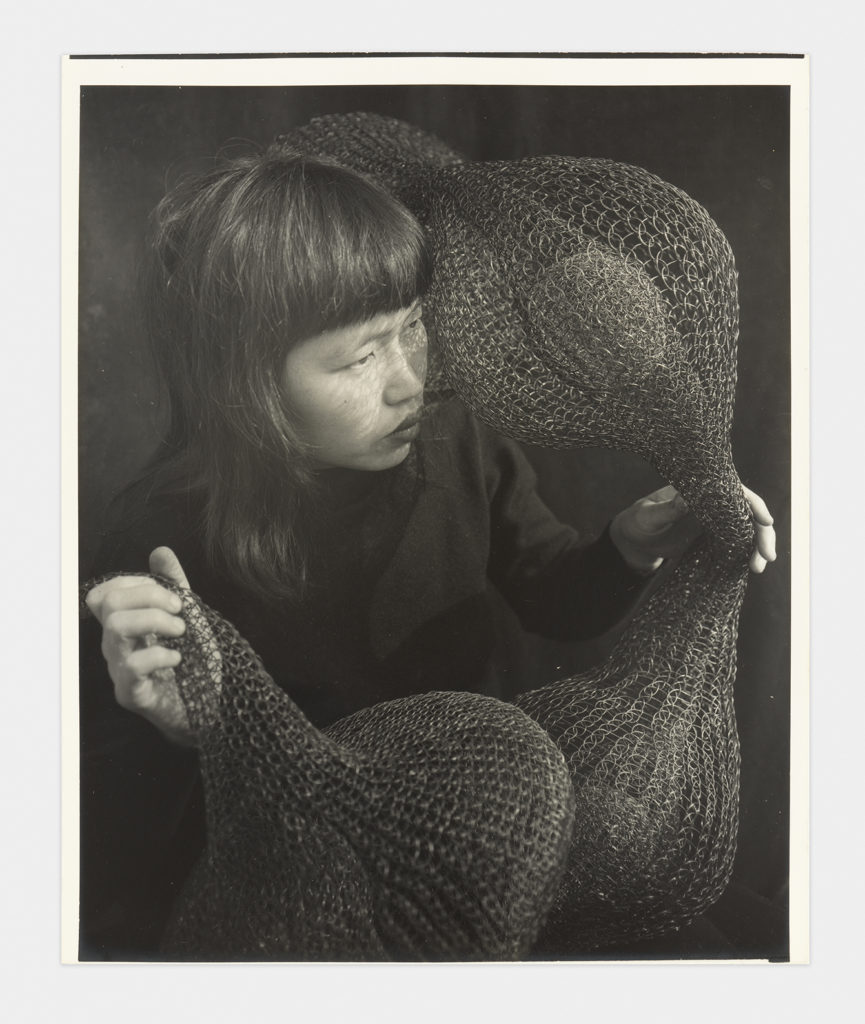

Now Zwirner’s first solo exhibition of Asawa’s ethereal, organically shaped sculptures, as well as rare early paintings, works on paper, and vintage photographs of her by Imogen Cunningham, go on view at the gallery’s West 20th Street space. A complementary show, “Josef and Anni and Ruth and Ray,” which opens on September 20 at Zwirner’s new space on East 69th Street, focuses on the constellation of creative relationships between Josef and Anni Albers—émigrés from Germany who brought Bauhaus principles to their teaching at Black Mountain College—and their student Ray Johnson, who met Asawa at the Milwaukee State Teachers College and convinced her to come to North Carolina in 1946.

Born in 1926 in rural California to Japanese immigrants, Asawa and her family were relocated to two internment camps for Japanese Americans during World War II. Asawa first learned to draw from fellow detainees who had worked as animators at Walt Disney. She later received a scholarship to attend college in Milwaukee, but left after Johnson spelled out the difficulty she would have getting hired as a teacher because of her Japanese heritage.

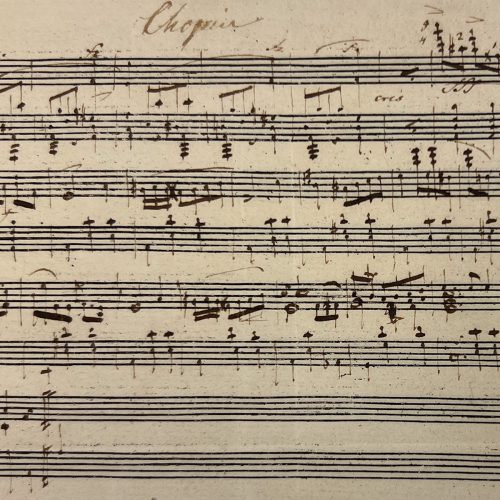

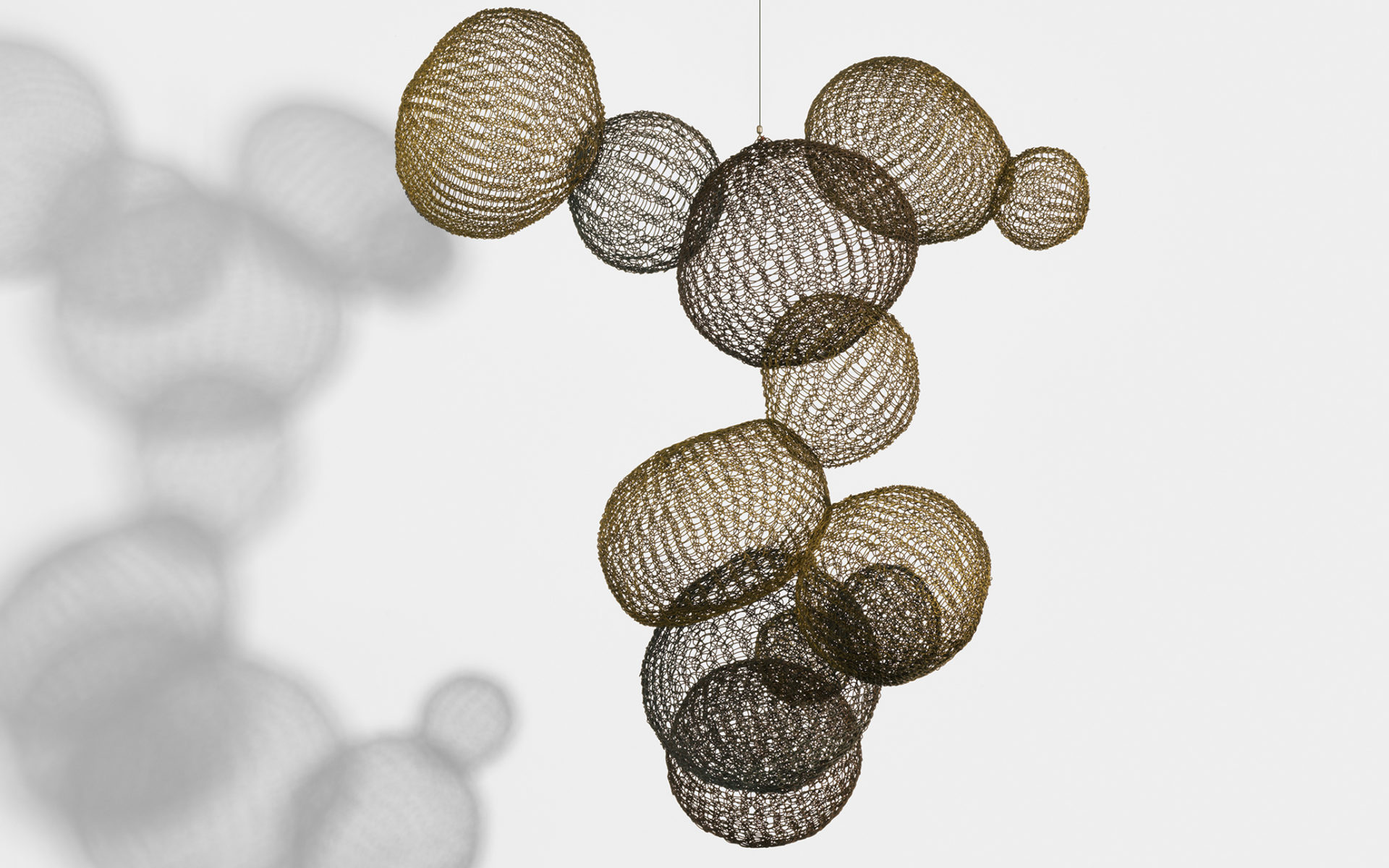

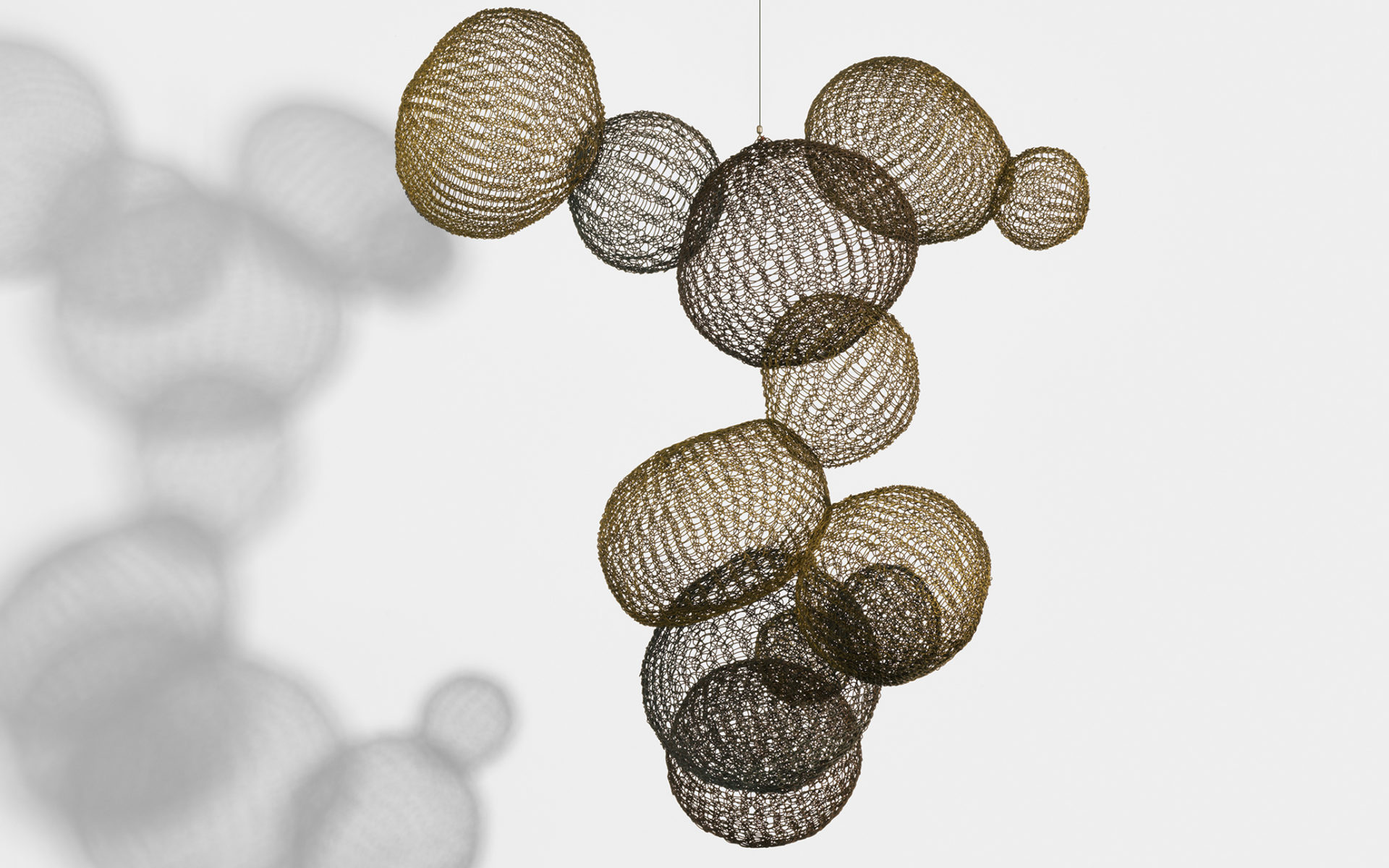

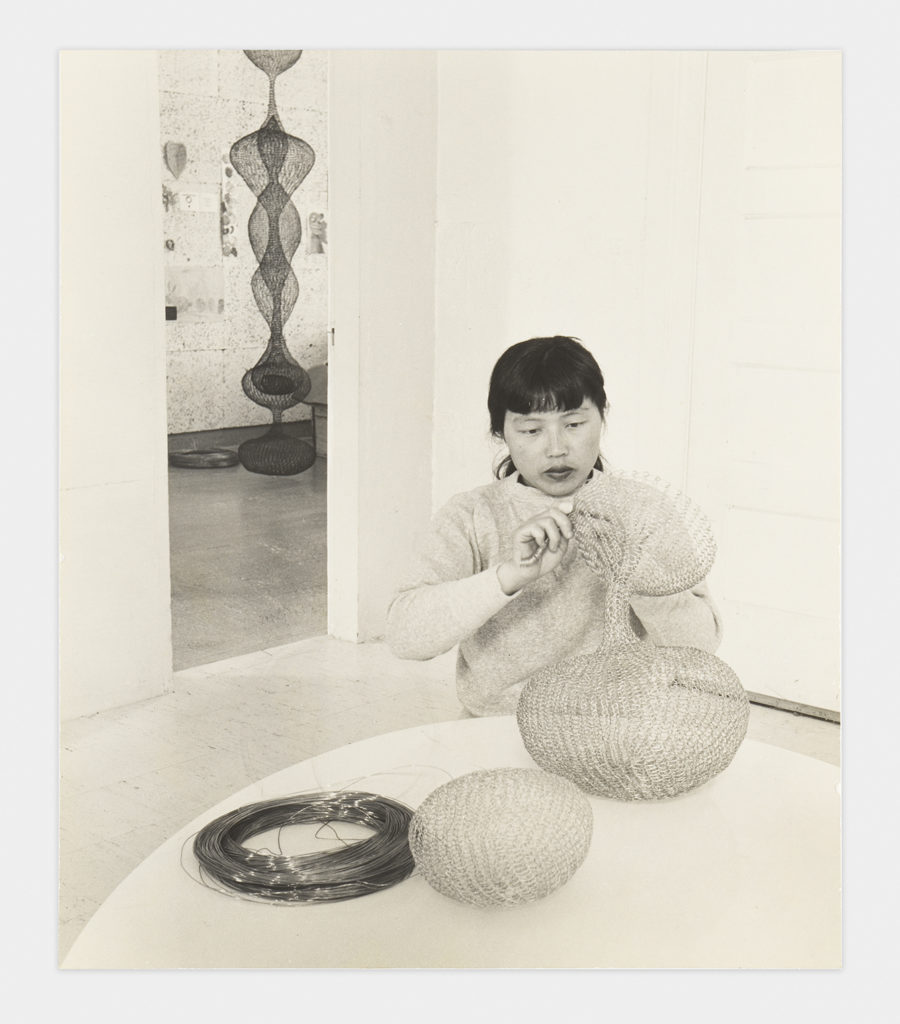

Asawa credited Josef Albers with opening her mind to the complexities of form, composition, transparency, and material experimentation. During a 1947 trip to Mexico, she learned to weave wire baskets from townspeople who sold eggs at the market. Back in North Carolina, the artist adapted this technique by essentially drawing in space with continuous lines of looped wire that defined three-dimensional form. The 69th Street show includes her very first sinuous, closed-form hanging sculpture from 1949. “These forms were with her since she was a child,” says Laib, describing how Asawa, who learned calligraphy early on, would ride on the back of the truck on her family farm and drag her feet back and forth in the dirt, creating an undulating pattern. “That silhouette would become her longer looped-wire sculptures.”

After moving to San Francisco in 1949, Asawa had solo exhibitions in New York at the Peridot Gallery, which also showed artists such as Philip Guston and Louise Bourgeois. “But that context gets erased completely if you read any of the criticism from that time period,” says Laib. “They referred to Asawa’s sculpture as ‘women’s work.’ It was extremely pejorative.” The current exhibitions reposition Asawa as a precursor to American minimalist and post-minimalist sculptors.

About half of the roughly 90 works on view on 20th Street are sculptures, many with curvaceous wire forms nested inside larger rhythmic forms that hang from the ceiling and defy traditional sculptural ideas about mass and weight in their sheerness and buoyancy. Others are from Asawa’s less-well-known series of wall-mounted tied-wire sculptures, which were begun in 1962 and echo how plants split and branch in nature. “Color’s not something you typically think about with her sculpture,” says Laib. “But when you see a roomful of them, you get that sense of color from the different types of wire—from copper wire to gold-filled wire to iron wire.”

Also included are paintings with graphic optical effects that Asawa made at Black Mountain College and works on paper of plant life that she drew from direct observation, without lifting her marker. “Her continuous lines are something that’s carried through,” says Laib, “whether it’s the two-dimensional drawing of geraniums or one of the sculptures hanging from the ceiling.”

“Ruth Asawa” is on display at David Zwirner’s West 20th Street gallery, in New York, from September 13 to October 21, 2017. davidzwirner.com