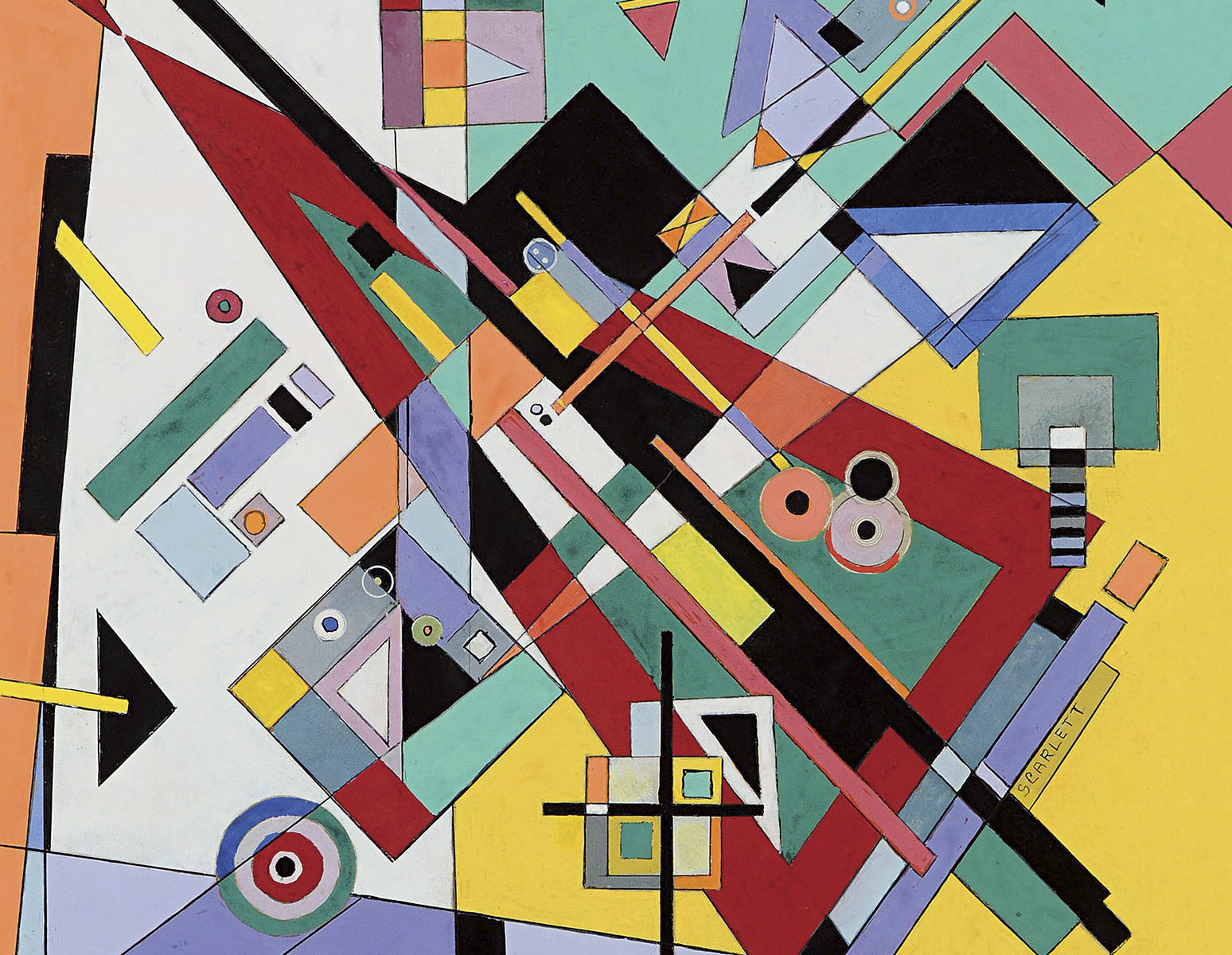

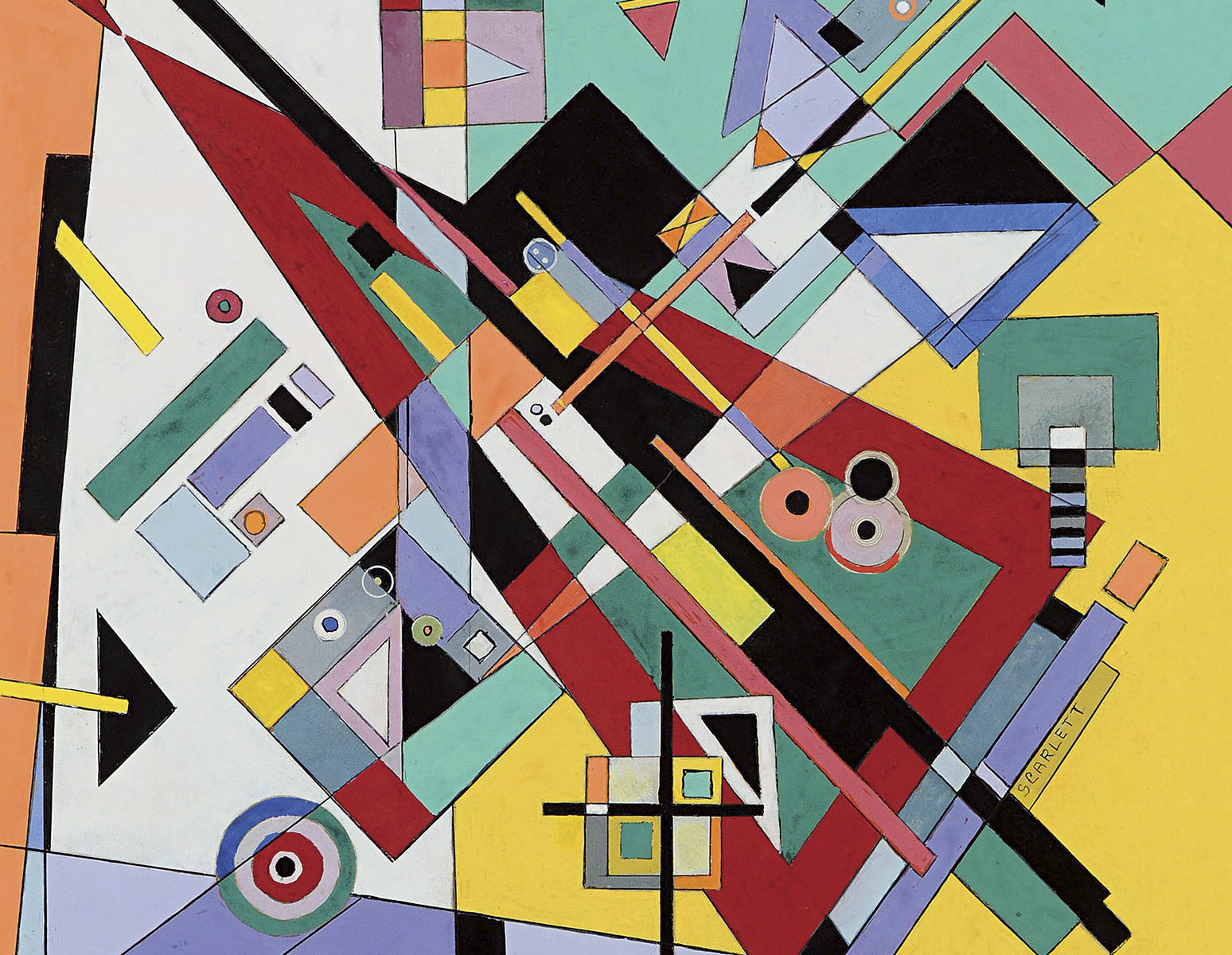

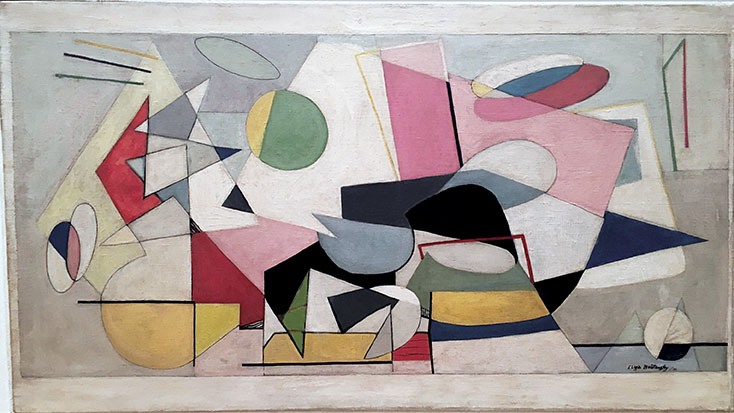

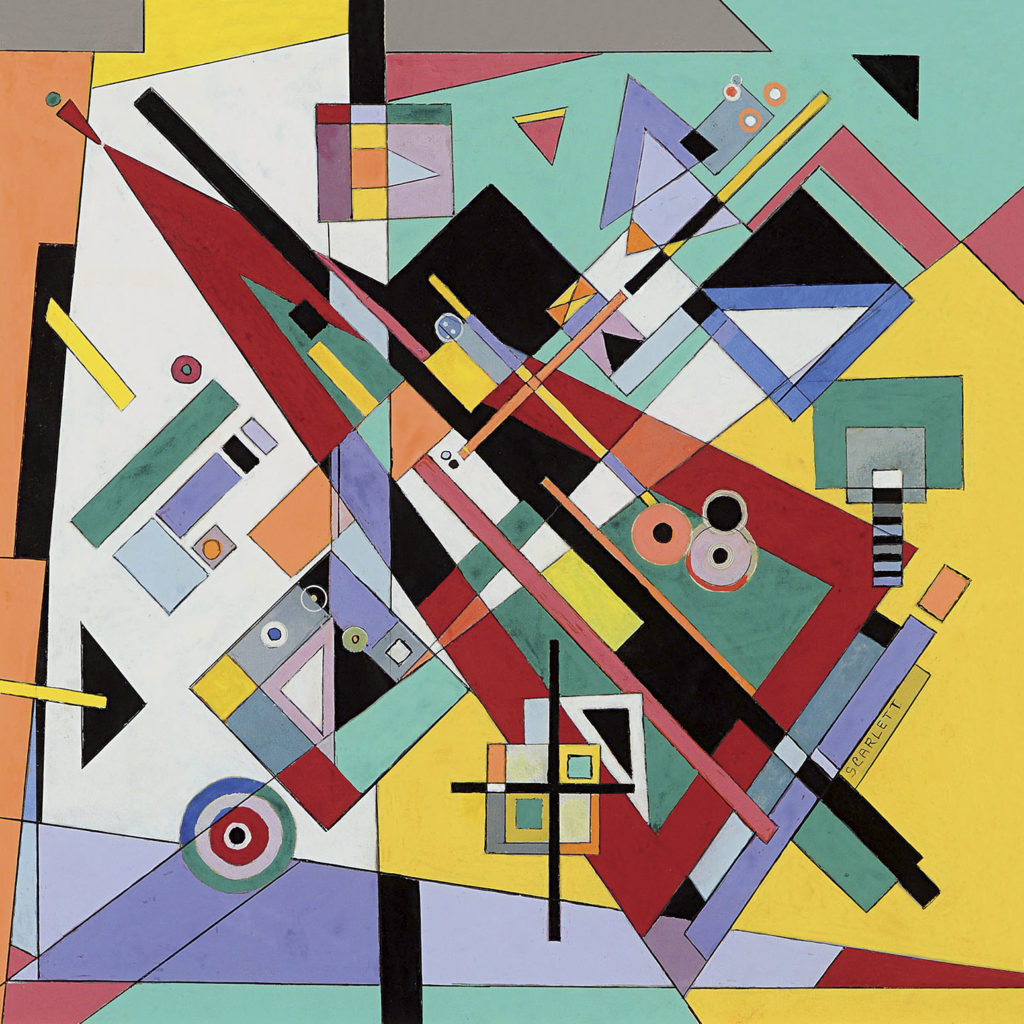

Rolph Scarlett, Abstraction, circa 1945.

Rolph Scarlett, Abstraction, circa 1945.

Like all great stories, this one began with a love affair. Actually, two of them. On the eve of the Second World War, brilliant art curator and German baroness Hilla von Rebay found herself entangled with two men. One was the gifted German artist Rudolf Bauer, a pioneer of the radical Non-Objective Painting movement who had been branded a degenerate by the Nazis. The other was the older American art-collecting millionaire, Solomon R. Guggenheim, rumored to be in love with the curator. She encouraged him to establish a museum devoted to modern art—including the work of his rival suitor. The museum, opened in midtown Manhattan in 1939, became an important early U.S. showcase for such leading European modernists as Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, and Wassily Kandinsky, as well as some of the hottest American art stars of the day.

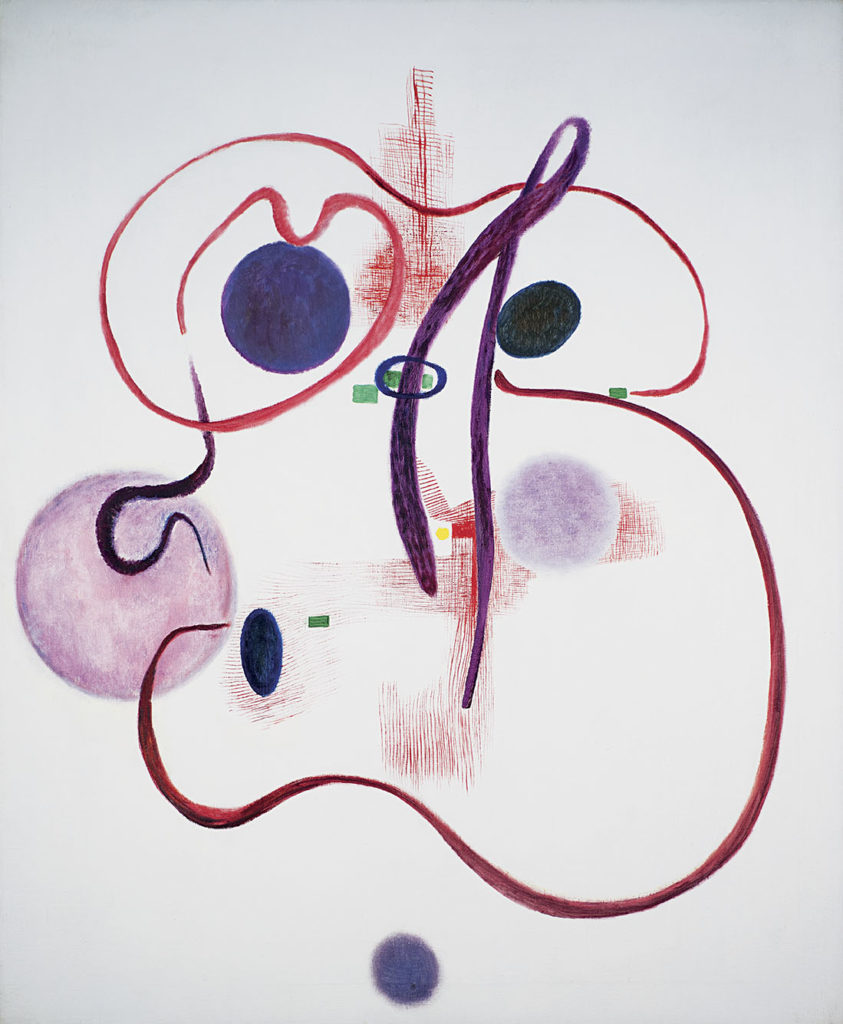

Hilla Rebay’s Delicate, 1950. Photo: Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery

But when Guggenheim died a decade later, his wife and his nephew seized control of the museum, recast its mission, and unceremoniously booted the curator- slash-alleged-mistress. They also removed all of the rival lover Bauer’s works from view, despite his long involvement with the project and his undisputed talent. Other artists the curator had championed were similarly culled, a reshuffling that would impact the narrative of 20th-century art.

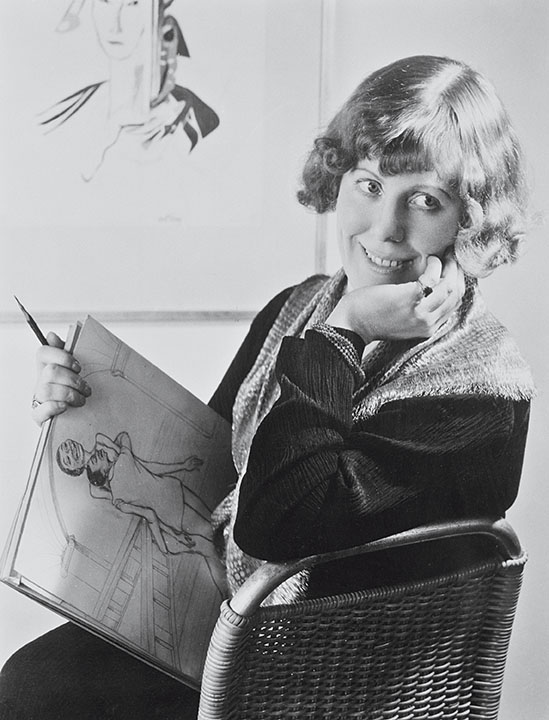

Hilla Rebay, photographed by Eugene Hutchinson in her Carnegie Hall studio in 1935. Photo: Eugene Hutchinson, Courtesy of HvRF Archives

“Would art history have been different if Solomon R. Guggenheim had outlived his spouse?” asks Phyllis Tuchman, art historian and critic. “Perhaps it would.” Tuchman wrote the catalogue essay for an ambitious exhibition that New York’s Leila Heller Gallery staged recently about that critical moment. Titled “The Museum of Non-Objective Painting: The Birth of the Guggenheim,” the show overlapped intriguingly with the blockbuster “Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim,” on view at the Fifth Avenue museum through September 6. The larger show highlights the key figures who contributed to building the institution’s distinguished collection, from Guggenheim himself to prominent German art dealers Justin K. Thannhauser and Karl Nierendorf to legendary collector Peggy Guggenheim, Solomon’s niece.

While the pivotal roles played by Rebay and Solomon Guggenheim are well chronicled, the third key figure at the heart of the Leila Heller show, Bauer, is really the odd man out. Far from a household name today, at mid-century Bauer was set to be a star of the new Guggenheim Museum designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. (Back then its name was to remain the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, a description Guggenheim preferred over the term “abstract art.”) Guggenheim had embraced Bauer’s richly colored and sophisticated geometric compositions, and filled his apartment at the Plaza Hotel with the artist’s work.

First Study for Williamsburg Mural, 1936 by Ilya Bolotowsky. Photo: Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery

Cover: Rolph Scarlett, Abstraction, circa 1945.

What happened? According to San Francisco gallerist Rowland Weinstein, Rebay’s obsession with Bauer backfired on the artist. “Her overpromotion of his work became notorious,” says Weinstein, who manages the Bauer estate. When Rebay lost clout, her lover tumbled from visibility.

Rolph Scarlett, Abstraction, circa 1945. Photo: Courtesy of Leila Heller Gallery

Bauer certainly wasn’t the only artist disadvantaged, to say the least, by Guggenheim’s death. Irene Rice Pereira, a founder of New York’s Design Laboratory school in the ’30s, was among the first American women to receive a retrospective at a major New York museum. Featured in the original Museum of Non-Objective Painting, her works were mostly relegated to storage when the new building opened in 1959. Charles G. Shaw, of the so-called Park Avenue Cubists, wound up only nominally represented. Painter Rolph Scarlett lost his chief source of support when his patron Guggenheim died. In his own account of the politics surrounding the museum, Scarlett claimed that, although Guggenheim had considered his choices to be the “art of the future,” Scarlett had been “buried” along with many of the collector’s favorite artists.

The Leila Heller show turned a spotlight back on these underappreciated talents, including Rebay herself. Since some works were once in Guggenheim’s personal collection, and given the concurrent exhibition at the museum, Heller says, “it seemed like a perfect time to do this show.”

In the end it was the select group of European artists preferred by Guggenheim’s heirs who won the day—and the lion’s share of pages in the history books. In the case of greats like Kandinsky, one can hardly argue. But while looking back at the loves of Guggenheim, art and otherwise, can’t reverse history for Bauer and company, it does help flesh out a narrative too often narrowly told.