Legendary Architect Harrie T. Lindeberg’s Legacy Celebrated in New Book

Architect Peter Pennoyer and historian Anne Walker reflect on the undersung talent

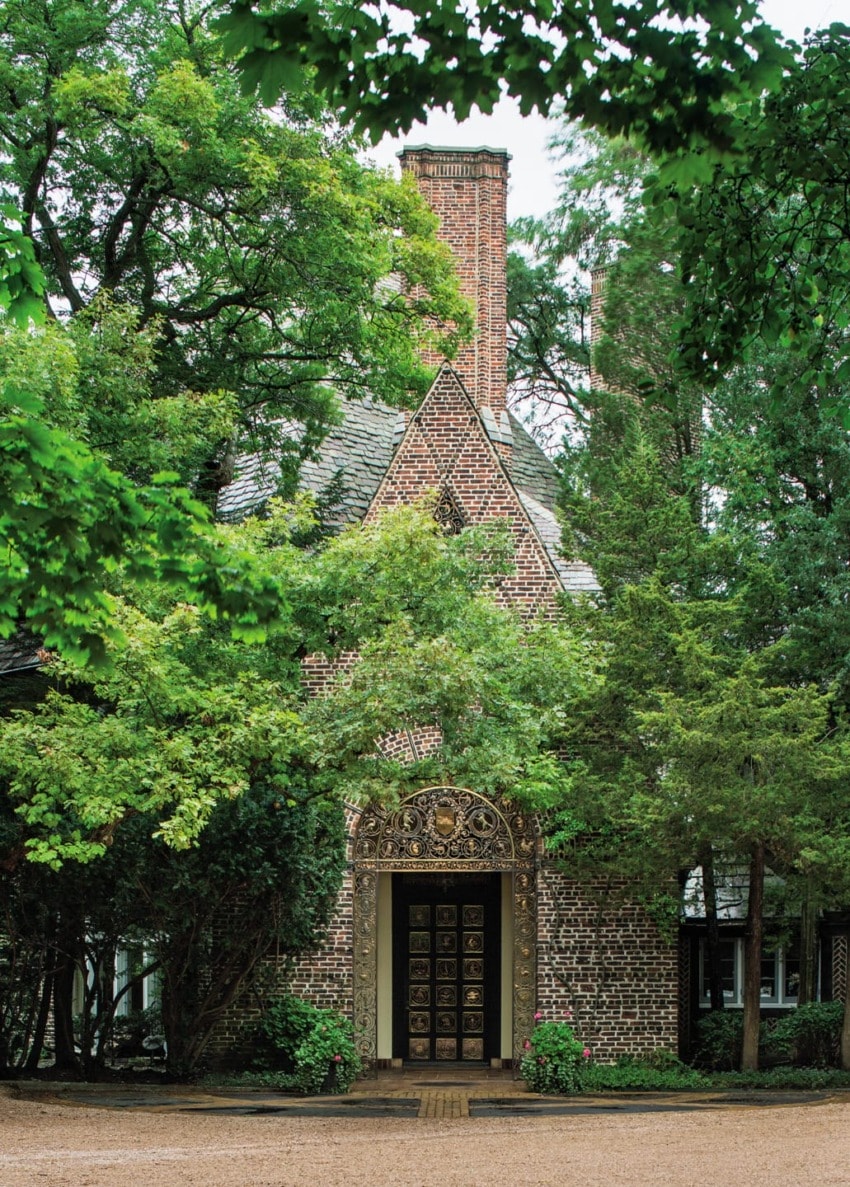

A caretaker’s house built around the individual branches of a tree. A doorway of hammered bronze panels depicting the signs of the zodiac. Roof eaves that curve over the sides of a house like a blanket. These stunning design details are brilliant examples of the singular craft and imagination of architect Harrie T. Lindeberg, who practiced in New York at the beginning of the 1900s.

Although not nearly a household name, Lindeberg’s fingerprints can be seen on American country homes built over the last century. His use of modest materials and graceful proportions made him the go-to talent for captains of industry, who wanted to escape the rigors of the city for a more relaxed country life. The estates he created for them celebrated nature, opted for humility over grandeur, and were strikingly simple despite their mixing of architectural styles.

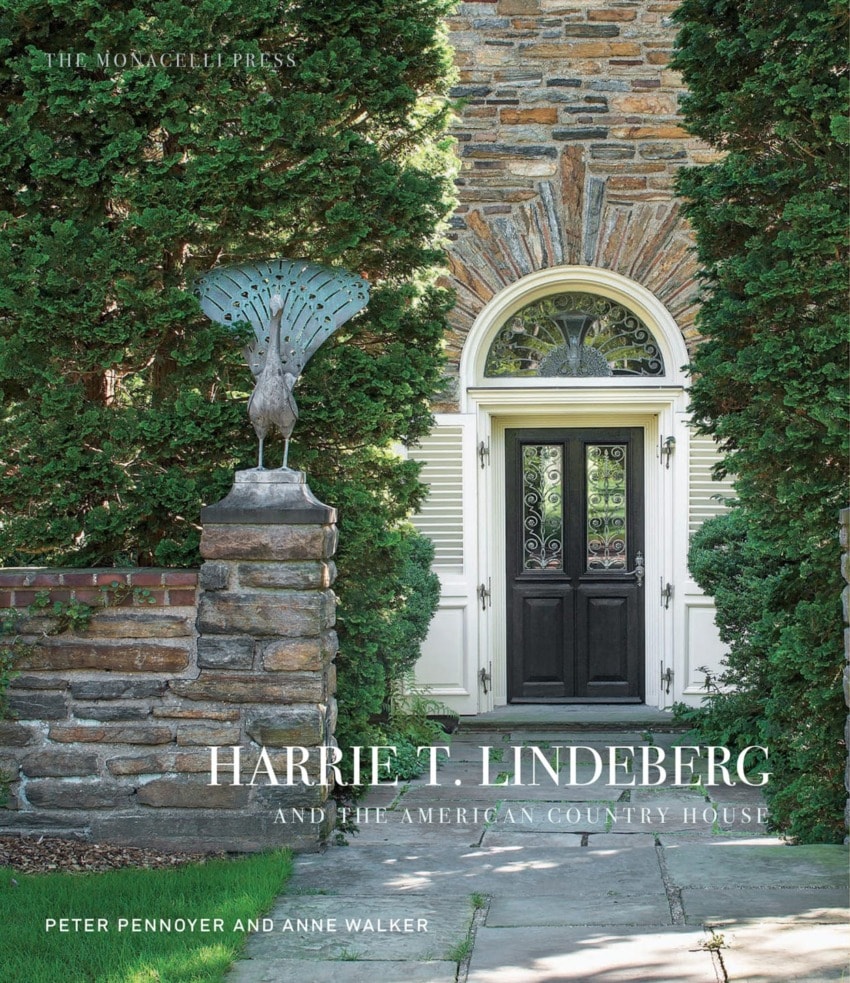

In the new book Harrie T. Lindeberg and the American Country House (The Monacelli Press, $60), architect Peter Pennoyer and historian Anne Walker reflect on what makes the homes created by the under-recognized Lindeberg such marvels even today. New as well as historic photography, floor plans, and sketches of 20 of the architect’s projects compromise the new tome, which picks up where Lindeberg’s out-of-print monograph from the 1940s left off. The enthusiasm and appreciation Pennoyer and Walker have for his work leap off the pages, which are brimming with interesting facts and keen observations on the signatures of his varying style. “He’s a great creator but also a great editor,” enthuses Pennoyer. “He was overflowing with creativity—not in an abstract manner, in a very detailed way. But he still was able to pare everything back to essential language of architecture.”

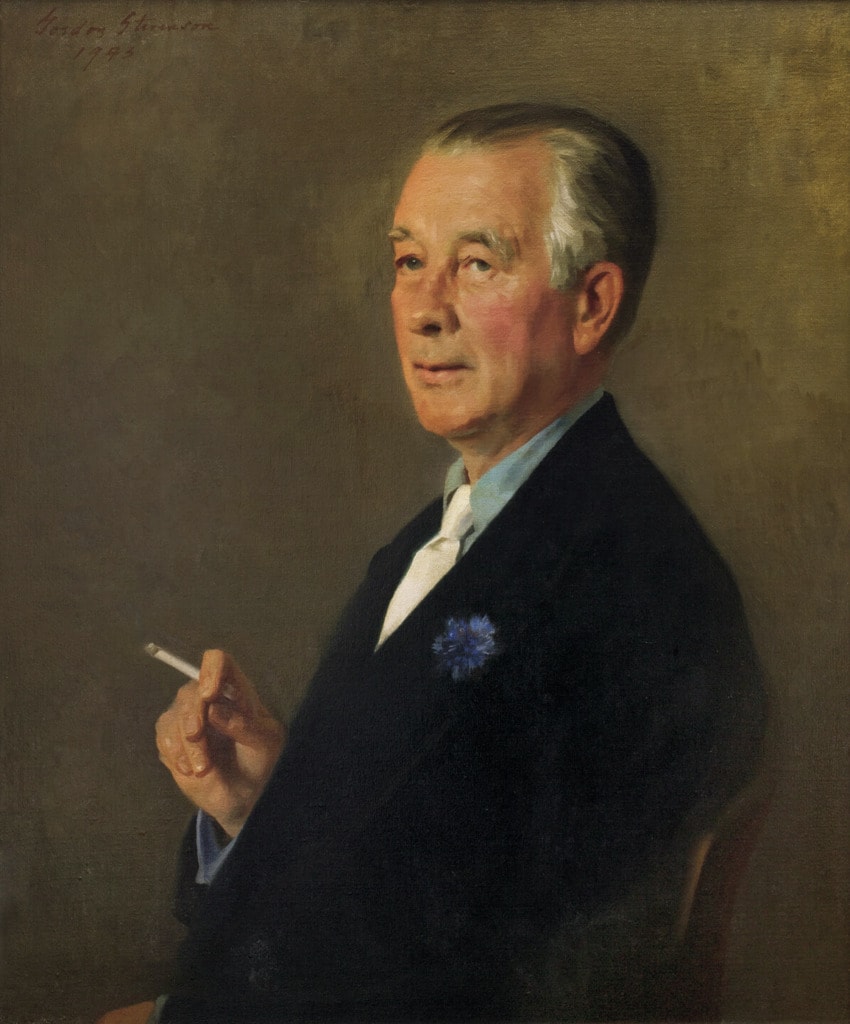

The child of Swedish immigrants, Lindeberg launched his career as an apprentice at the age of 17. By 24, he was managing a team of four graduates of the Harvard School of Architecture although he had no degree himself. Five years later, Lindeberg launched his own practice, which became the firm of choice for industrial titans looking to build gracious country estates in upper-crust New York enclaves like Glen Cove, Mill Neck, and Rhinebeck—as well as St. Louis, Missouri, and Lake Forest, Illinois. His designs even were even built abroad as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s quest to export American architecture with the construction of the United States Legation in Helsinki.

In his foreword to the book, Robert A.M. Stern observes, “Harrie T. Lindeberg was not an eclectic architect working in identifiable historical styles but instead a traditional architect who drew upon diverse sources, which he did his best to conceal, synthesizing them into an identifiable personal style.” He goes on to liken this ability most closely to that of Frank Lloyd Wright, “who despite his claims to not be a traditionalist also drew from the past and from the work of his contemporaries but concealed the sources of his inspiration.”